Everything is in some way aesthetic, art and literature, of course, but also refrigerators and cell phones, the way we speak and the structure of ideas. And this matters if we want to appreciate foreign cultures.

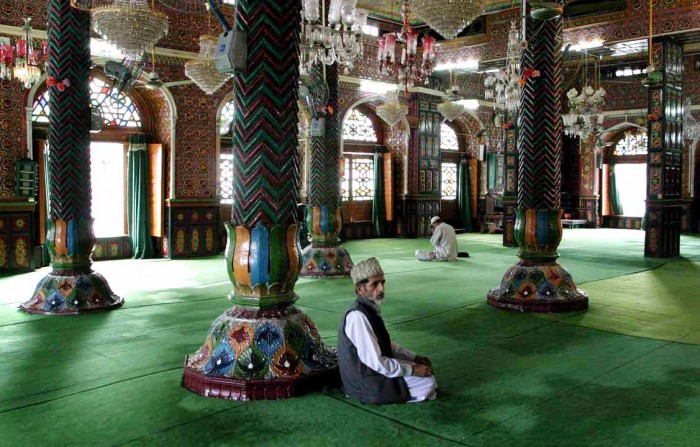

Everything is more or less beautiful, more or less harmonious, more or less attractive, more or less fitting. Hence, our experiences of other cultures tend to be highly aesthetic. The problem is that while many aesthetic experiences seem to be innate and hence universally accessible, much aesthetic appreciation must be cultivated. It is difficult to appreciate the layered complexity of a symphony if you have never been exposed to such sounds before, after all. The exalted state that comes from reading the Qur’an or the Gospels, the sense of wonder that comes from gazing upon the New York skyline, are cultivated through our understanding of what lies beneath the surface. And this is where it gets interesting.

Many of the most beautiful and awe inspiring aspects of other cultures will be closed to us because we have not cultivated the ability to appreciate them in all of their glory. Perhaps this is not true for great architectural works like St. Peter’s Cathedral or the Taj Mahal. Such productions can engulf us, transport us outside of ourselves. But the opposite is more often than not the case with music and literature.

The simplistic repetition of African stories, the rhythmic and atonal complexity of Indian sitar music, must often be adjusted to before they are appreciated. And what is true for much of the arts is even more so for the interiors of homes and styles of clothing. Such things are intimately close to our truest and fullest selves. They signal to us that we have arrived or that we are whole. And they seem to differ everywhere.

The ability to appreciate such different styles is such a powerful solvent that it might dissolve much of the differences between Islam and the West. For the language barriers are often as aesthetic as they are verbal.

It is much the same with gesticulations and manners of speaking, the pace and tone with which stories are told, the level of disagreement that is acceptable and enjoyable in conversation. The problem is not so much that we will misunderstand one another across some cultural chasm, though this is bad enough. There is a deeper danger with our failure to cultivate an appreciation for the mannerisms of other peoples and that is that we will find them disgusting.

Much of our revulsion for the otherness of peoples with whom we are unaccustomed seems to spring from this failure to cultivate an aesthetic appreciation for their ways of being. So, the problem many people in the West have with the Muslim hijab, the veil that Muslim women often use to cover their heads, is not just a problem of misunderstood meanings, not just a problem even of the failure to honor a different way of being in the world. It is often the result of a failure to cultivate an appreciation for a cultural form with which we are unaccustomed.

We do not find it beautiful because we have not looked closely at the beauty of the women behind it and the way they express a subtler, more modest beauty that tends to go unnoticed in the West.

This is why it is sometimes necessary to immerse ourselves in the cultural productions of some group before we can truly grasp what they have to offer. We have to sink into their rhythm of life, their pacing of conversation, their literature, music, history, and religion. In doing so, we are not only cultivating an appreciation for different patterns of aesthetic experience. For cultural productions tend to be self-referential as well.

The founding of nations, the failure of revolutions, the most moving passages of spiritual scriptures will all tend to echo through literature and music and poetry across the ages. And they often lie at the heart of how whole peoples conceive of themselves and what they have in common. When the Chinese are reduced to mute conformists, Arabs into reactive fanatics, African-Americans into mere expressions of the body and emotionality, we can see at work this same failure to grasp wider cultural references and patterns of experience.

None of this should imply that there are not certain universal patterns of beauty recognizable across cultures. These too can unite us and enrich our lives. And they might form the basis for a global language of beauty. But appreciating one another in all of our richness and vivid detail will require some work.

Just as we must often work to understand and appreciate our own cultures, we must do so with the cultures of others. And in doing so, we will not only enrich our own lives but the shared spaces in which we all come together. We can think of this as yet another aspect of crafting a global civilization or simply another way of being human in an increasingly diverse world.

Relephant:

A History of Global Consciousness.

Author: Theo Horesh

Editor: Travis May

Photo: Wikipedia

Read 0 comments and reply