When I was trying to be a yogi, I wasn’t being myself.

I didn’t intend to stop doing yoga.

I had practiced fairly consistently for more than a decade, beginning with ashtanga, switching to Baron Baptiste’s Power Yoga (Boston, Denver) before migrating to Forrest yoga (Denver) where I ultimately and joyfully did a handstand. But a leg and foot injury I sustained while completing Spain’s El Camino de Santiago in autumn of 2012 made many standing yoga positions painful if not impossible.

My quest for relief led me to a podiatrist, two physical therapists, a deep tissue masseuse and a Rolfer. Despite dry needle treatments and a third set of custom orthotics, my injury showed few signs of healing. I couldn’t spend much time on my feet, period, let alone hike, dance or do yoga, activities that boosted my spirit and kept me from teetering into depression. I took up swimming and, after doing laps daily, developed a chlorine allergy.

That summer, I rented a room in Boulder so I could swim in its reservoir. That wasn’t enough to keep my spirits afloat. When I stumbled across and limped into a Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement class, I was desperate. The Facebook ad said the class involved slow, gentle movements.

Those I could do, even though I yearned to do large, vigorous ones.

In that first lesson, a handful of us in street clothes lay down on folded, denim blue moving blankets. The teacher guided us through a series of movements that, for me, were excruciatingly slow and numbingly repetitive, with no obvious goal. He told us to move even more slowly and not approach our full range.

Then, he told us to rest.

My monkey mind went berserk: “Rest? We have barely budged! We have not broken a sweat!!” “This is boring!” “This is for old people!” “When will this nonsense be over?”

After enduring 45 minutes of self-inflicted torture while moving slowly, I heard the teacher tell us to stand and notice any differences. To my astonishment, I felt refreshed and extremely present, as if someone had hit the reset button on my nervous system.

Gone were the anxiety and despair I had experienced less than an hour before, even though my life circumstances were unchanged and my leg still hurt. But I had changed, in a way that I couldn’t immediately comprehend, let alone explain. The shift in my sense of self felt more profound than anything I had ever experienced in yoga, despite years of practice. My leg injury, which had dominated my emotional landscape for months, suddenly receded into the background. I knew I’d be fine even if I never bagged another peak.

Each time I returned to class, I experienced magic. I stopped resenting the unglamorous, pose-less and pointless movements and appreciated that they helped me learn to pay extremely close attention to myself.

I began reading books by Moshe Feldenkrais, the Jewish physicist, engineer and Judo master who developed his method while healing his own incapacitating knee injuries. I became more fascinated with, than frustrated by, the mechanics of my injury and began to view my chronic but intermittent hip pain, for which I once found temporary relief in pigeon pose, as a puzzle to solve or a code to crack, rather than continuing to believe what many yoga teachers had said, that “grief is stored in the hips.”

The more I practiced Feldenkrais, the more I appreciated its premise. In a society acculturated to fast, dynamic or sexy moves, the Feldenkrais Method can seem baffling. But the idea behind the small and sometimes barely perceptible movements is simple: moving very slowly, in a limited range and with awareness helps the brain discern differences so it can choose the easier pathway. The brain, like a wine connoisseur, samples small amounts to make distinctions. It requires periodic pauses to integrate the new information.

Moving quickly or with too much effort is, from the brain’s standpoint, a bit like getting drunk: it might feel good temporarily but is less likely to lead to improved functioning.

The more I immersed myself in Feldenkrais, the more I valued its low frills culture. That students often wear regular clothing was a huge relief from the Lululemon “look” infiltrating the yoga world. That I didn’t break a sweat meant I could attend class without needing to shower afterward, simplifying logistics. That there are no poses, only suggestions for movement, allowed me to find my own way of doing things, without comparing myself to others or being adjusted. That the Feldenkrais classes lacked the beehive vibe of many yoga studios made me, a highly sensitive introvert, feel more comfortable.

I liked Feldenkrais so much I enrolled in a training program to deepen my somatic awareness. I’m still years from being certified, but even after 11 weeks of training over nine months, here’s a short list of what I’ve observed from moving slowly while lying, sitting or rolling on the floor:

- My hip pain has resolved almost completely, which hundreds of pigeon poses didn’t address

- My vertebrae stack comfortably and effortlessly when I meditate, without my having to adjust my alignment

- My breathing is consistently deeper and more relaxed

- My body moves with an unprecedented lightness and ease that feels miraculous

Since the Feldenkrais Method makes all movement easier—whether that’s getting out of a chair, onto a horse, or into chaturanga—many yoga poses are probably more accessible to me today than when I was trying to be a yogi. And that, I see now, was precisely the problem: when I did yoga, I was trying to be someone I wasn’t. With Feldenkrais, I feel more like myself and more at one with the world.

*

Relephant Read:

Are we Ready for a Slow Yoga Movement?

Author: Ilona Fried

Editor: Renée Picard

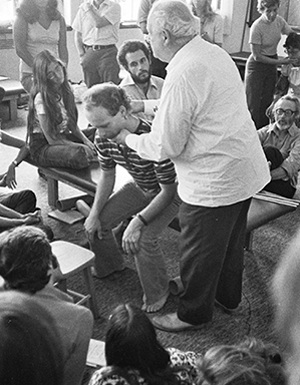

Photo: Wiki Commons

Read 50 comments and reply