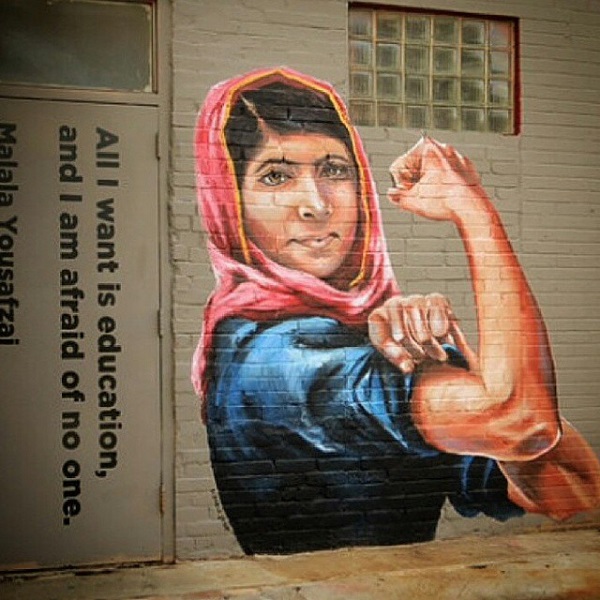

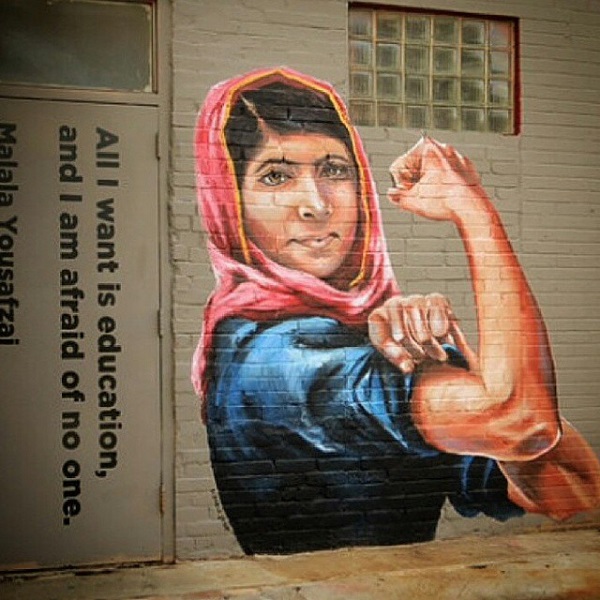

On her 18th birthday, Nobel Prizewinner, girls’ education advocate, Taliban-thwarter, and all-around good egg Malala Yousafzi opened a school in Lebanon for refugee girls who have fled violence in Syria.

Naturally.

The situation at the refugee camps is dire. Over the past four years, civil war has driven millions of Syrian civilians into neighboring countries. These displaced persons are scrabbling for existence, rolling over the border with countless traumas on their backs, plus all the everyday emergencies of human life. Host countries are struggling to cope with the influx of refugees and complaining, somewhat understandably, that they aren’t sure how many more people they can take in.

It is into this deluge of human pain that Malala walked on the day she became an adult, carrying her mission of educating girls.

Of course she is there. Of course she is doing this thing.

She is Malala.

I read of her birthday celebration and smile broadly for the gratitude of sharing the earth with bright Malala, She Who Goes Into Dark Places With Light. I grin also in remembrance of myself—my 18 year old self—and what I yearned for at that age.

At 18, I dreamed passionately not of greatness, but of goodness: I wanted to be a person who did something.

I wanted to save dolphins and close sweat shops and give justice to those who ached for it. I wanted to do all the good things.

When I think of Malala now, unbidden comes the word: sister.

Quickly I bat this thought away.

No; that cannot be so. It is pretentious even to suggest it. Her life is nothing like mine; hers has been so much more.

She is Malala, and I am just—well, just me.

My childhood was far from sheltered, but it was not Pakistan.

Oh, yes: I was harangued by creeping, ill-mannered adults when riding public transportation across an impoverished city to school; but I was never shot, as was Malala in 2012.

As a schoolgirl in an unfriendly place, my foes were potential sexual predators, and that was a hideous, fearsome experience. But for heaven’s sake: I never had to face down the Taliban.

My early life, for all its raggedness, was not Malala’s.

There was a time—maybe, when I was 18, if I had been a bit smarter about it—that I could have gone and done Malala-like things, maybe even on a Malala-like scale.

At 18, I was already a sophomore in college—early admission, thank you—and confident that despite a dismal start in life, my arc had been launched high. With near–Dickensian great expectations, I felt certain that good doings would fall quite naturally from my fingertips.

As it turned out, I actually had no idea how to manifest any of my world-changing daydreams in reality.

I had a head full of ideals, but very little understanding of my skills, and even lesser grasp of what greater good they might be used for.

I could write papers. I could test well. I could devour books like snack cakes. I could construct a logical argument. I could listen, maybe a little better and a little closer than others. I found it easy to memorize the map of the world and track something cogent and relevant within its history.

But none of these things seemed to bear any connection to the world-changing path of advocacy I felt tingling in my 18-year-old hands.

At 18, I could not even articulate just how I wanted to change the world.

“Do good” was all I could muster.

I wound up in a service-oriented law school.

(Yes: put the lawyer jokes aside, and know that such institutions do exist.) I hoped that place could teach me to do the big, good things I was so itching to do.

And indeed, while I was there, I met people who would go on to partake in world-changing activities. They would storm the proverbial Bastille for the cause of equality. They would lead task forces in the name of justice. They would organize national charity movements. They would be spokespeople and respected advocates, and I would cheer them with all my heart.

But when I entered the workforce, I could not do what my peers did. I no longer had time.

Family needs pressed in upon me; I needed life to be smaller, more predictable.

I took an entry level job in a suburban public defender’s office, still attempting, somehow, to do some good.

But let us be honest: no one really thinks of defense attorneys as agents of good.

I worked the most mundane sorts of cases countless times over. It was gritty, depressing, simultaneously monotonous and shocking. The work was not entirely thankless, but the thanks were very few and far between.

It was not a big, good thing.

It was arguably not even good.

It was nothing like what I’d dreamed of at age 18. Really, for anyone dreaming of doing big, good things, this would seem like a thorough failure.

Looking at people like Malala, they can seem so impossibly good—almost inhuman.

How can they do such things at such a young age? How are any of the rest of us ever supposed to measure up?

But then I go back to being 18, and recall the drum that pulsed in my heart: what that felt like, what I really loved about it, what I wanted then—what I still want, now that I know myself a little better.

Doing good isn’t about measuring up. It’s about making more of the light and less of the fear, hurt, hate, whatever it is that has kept the light at bay.

And the good we do need not be big to the whole world.

A client kissed me once; just on the cheek. She was a grandmother, who had never known courthouses as anything more than “where weddings happen for people who ain’t been to church enough.”

When she heard she had been acquitted of theft (a vicious crime alleging the loss of precisely six quarters), she could not contain herself. She wept and blessed me. She squeezed me so hard it impacted my contact lenses.

(That is how I explained the tears to the bailiff.)

It was the “smallest” trial of my career, but to that grandmother, it was her whole world. Winning that case for her was one of the biggest good things I have ever done.

It was not the sort of good my classmates were doing, and certainly not the sort of good Malala is doing, but maybe—maybe we draw too much association between good-doing and big-doing.

We cannot all be Malala. We don’t need to be: She is Malala.

And to all the do-good hearts, yes, I think she is sister.

I posit that we are all capable of doing tremendous, furious deeds of good on our own small scale.

This starts with looking honestly at ourselves. We must acknowledge our talents and strengths, and not be shy about them. We must know our powers, our privileges, our resources. We must know what we control and influence.

Are words your gift? Spill them. Sing them. Scribe them shouting wherever you can

Are you a healer? Oh, darling: touch, study, gift your medicines.

Are you a gatekeeper? Open whatever doors to which you hold keys. Help the people come through.

Consider this, world-changers: how we behave to one small child entrusted even briefly to our care is of tremendous import to generations upon generations unseen, unknown.

We must acknowledge our weaknesses as well.

We must know our shadows—for here, among our mistakes and jagged places, sit some of our strongest elements. Our experiences as survivors, as overcomers, as healers, as evolvers hold vast potential.

Our wounds allow us to empathize with one another, to reach over time, language, culture; to take up hands.

I cannot go to Lebanon and start schools for young women. But there are a heck of a lot of very good things which I am very empowered to do.

World-changers, the lesson I missed at the age of 18 was that advocacy begins with self.

Malala did not leap over the world to tackle some big thing because it was a big thing; she simply got up and faced the problem she knew.

Know yourself, know your power, and go do good things.

Relephant:

Why Malala Should have Won the Nobel Prize.

Author: K.A. Laulumets

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: Bruno Sanchez-Andrade Nuño via Flickr

Read 2 comments and reply