It’s another day in the office—killing time for the majority of the day before my intensive outpatient substance abuse group begins at 5:30 p.m.

I usually do this by mindlessly scrolling through Facebook, trying to absorb every bit of insight and wisdom from Elephant Journal, and compulsively checking the Baltimore Sun Obituaries.

It sounds morbid, I know.

But since I work in the addictions counseling field, I hear countless stories of death-by-overdose or drunk driving accidents. A counselor I used to work with told me she kept the obituaries website on her saved tabs on Internet Explorer.

I decided to do the same.

At first, I felt an overwhelming sadness as I scrolled through the death notices.

Every day, in Baltimore city and county alone, there are many deaths.

I couldn’t even begin to grasp this—up until recently, my only experience with death had been my grandmother, with whom I hadn’t been close, and two friends in high school who tragically died in a car accident in the middle of our senior year.

Thanks to a raging alcohol addiction, I never actually processed those deaths.

Until recently.

I have been a sober member of a 12-step program for almost four years (on the 28th of August).

Just like the grapevine in the addictions counseling world, I had heard time and time again about heartbreaking overdoses of people who were seemingly “doing well” in the program.

In March, it was like any other day at work. I had a 10-minute break in between the first and second hour of group therapy, so I decided to go up to my office and check my phone. My best friend had sent me a text asking, “did you hear about Drew?” My first thought was that he may have relapsed, again. I had heard about a recent relapse of his a couple months earlier. This isn’t uncommon in the rooms of the 12-step program. Relapse is not a part of everyone’s story, but after being around for a bit of time, I am not as surprised when I hear about it.

“He overdosed,” she texted.

Again, this wasn’t uncommon. I coolly looked at the screen, texting back about if he’s in the hospital and doing okay.

“He died.”

I stared at the text.

I stared at it for what felt like hours.

I put my phone down, and walked back downstairs to go into the second hour of group. My face must have been white, because a co counselor asked if I was okay in our processing room while I was putting a patient’s chart away.

The floodgate burst open.

“My, my friend, he died. He overdosed. He’s dead.”

The counselors surrounded me. This particular friend had actually been a patient where I was currently working. They all knew him, they all loved him. He was one of the ones that you’d expect to make it. He was bright, ambitious, hilarious and young.

They forced me to go home. For some reason, as tears poured out of my eyes, I told them that I was okay and could go back into group and continue counseling. Thank God they knew better—it is incredibly unethical to be with a patient when you are emotionally distressed. I tried to be okay, I really did, but I couldn’t stop crying.

That night, I went to one of my normal 12-step meetings. It was his home-group (a group that you commit to going to every week). I sat with friends of his, with members who knew him, who didn’t. We listened to a girl’s inspirational story and sat with our tears. His sponsor was there and spoke. I cried and cried and cried, self conscious because I wasn’t his girlfriend or even his best friend.

I sat in my office, months later, scrolling through obituaries. It had become a habit.

Before Drew died, I talked in therapy and with my sponsor and close friends about how I was waiting for a patient to die. About how I knew it was going to happen, and I didn’t know when, and I didn’t know how to sit with that fear.

After Drew died, this fear was exacerbated. “Who’s it going to be next,” I would think to myself. Numbly detaching, carrying him with me in my heart with every opiate addict I counseled.

Months passed, and I didn’t see anyone I knew, either in the rooms of my 12-step program or patients, on the obituaries list. I almost wanted to see someone I knew. It became like a craving. I wanted to control the impending deaths. I started to expect to see them so much that I would become disappointed as I scrolled through the hundreds of names and faces I would never meet.

Then, one night, as I mindlessly scrolled right before meeting with a patient individually, I saw the picture of a 20-year-old patient who had just completed our I.O.P. program.

It hit me like tidal wave.

I felt it, bubbling up in my chest, willing me to feel.

This wasn’t the first time, and it won’t be the last time, that I see a name of a patient I’ve worked with on the obituary website. Since March, there have been five deaths from overdoses of people who I knew from the 12-step program or work.

It’s not going to stop here.

The harsh reality of addiction is that there is no cure. The harsh reality of a helping profession is that I cannot save anyone. The harsh reality of life is that I have absolutely no control over what is going to happen to others.

But I can do my part. I can show up. I can be a power of example. I can shine my light, both in the rooms of the 12-step program and with my patients, and share a message of hope.

And I can hold onto to hope for myself.

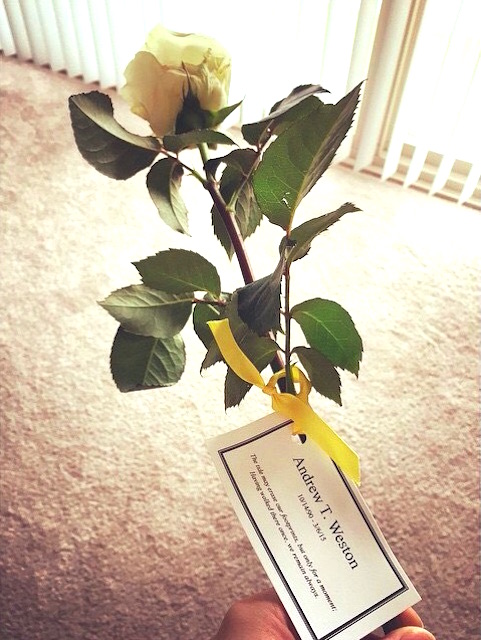

This is for you, Drew.

~

Relephant read:

The Value of Holding Space with Another’s Grief.

~

Author: Hannah Rose

Editor: Ashleigh Hitchcock

Photo: courtesy of the author, flickr

Read 0 comments and reply