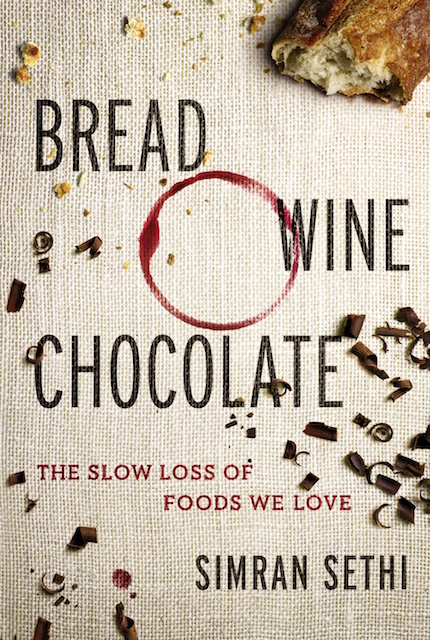

We are honored to share with you, our dear readers, an excerpt from “Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of the Foods We Love” by Simran Sethi one of ele’s long-time favorites.

Journalist and educator Simran Sethi’s new book, Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of the Foods We Love, is about the rich history—and uncertain future—of what we eat. The book traverses six continents to uncover the loss of biodiversity, told through an exploration of the senses and the stories of bread, wine, coffee, chocolate and beer. It’s a book about food, but really it’s a book about love.

~

I scanned the Peruvian customs form, similar to ones I had completed an endless number of times, but paused when I got to the question “Have you been on any farm?” The boots on my feet that had carried me from wild coffee forests to cacao plantations had been scrubbed clean. Bags that once carried heirloom seeds were, instead, stuffed with notes from my interviews on biodiversity. I checked the box “no,” despite knowing full well I carried each and every one of those places in and on me. Wendell Berry echoed through my head: “Eating is an agricultural act.”

Research shows we make about 200 more food decisions each day than we are aware of, most of which we consider “automatic,” informed by far more than what we are actually hungry for, including the time of day, the environment in which we eat our foods and the company we keep. Associate professor of psychology Katherine Appleton summarizes, “Few of us eat just because we are hungry.”

This recognition was solidified for me at the grocery store, the place where we started our journey and the first destination I seek out when visiting a new country. The areas where food is sold reveal a lot about a culture and what it values. “Tell me what you eat,” proclaimed French epicure Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, “and I will tell you who you are.”

Who I was had changed: I wandered through the aisles at the Vivanda grocery store in the Miraflores neighborhood of Lima, Peru, eager to try new things. It was winter of 2014, and I was in Peru for a forum on landscapes, development and climate change, excited to discuss agricultural impacts. Instead of toting my usual culinary touchstones (Ethiopian coffee, Aeropress coffeemaker and multiple bars of chocolate), all I wanted to do was try the new.

How did this happen? How did I move from safety to adventure? Which people, places and foods prompted the shift? I’m not sure. All I know is that it happened one meal at a time.

In the beginning of this book, I mentioned a study that asserts the way we get over our fear of new things is by trying them. But when I first typed those words, I wasn’t there yet. I was still living into that answer.

Although the romantic relationship I had hoped for (the one that prompted me to smoke and left me sad after sensory training) didn’t pan out, a different kind of connection had taken hold—one that allowed me to reach toward others and ask, “What are you eating?” This curiosity resulted in one shopkeeper closing her store early to walk me to the bakery she loved because she couldn’t bear the thought of me having a subpar baguette; and another to cook for me because she knew it brought me joy. It’s the connection that comes from knowing we are more alike than different—that to share a meal or a table is, in some small and meaningful way, a means to setting differences aside and joining together.

This journey was harder than expected. I travel—a lot—but my culinary adventures had always been constrained. The first time I tried to have a nice meal by myself was when I was 16. I joined my mother at a work conference in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. She had an evening function, so she handed me her credit card and steered me toward the nicest restaurant in the hotel. I had on my fanciest dress and my most mature affect, but the staff wasn’t buying it. They seated me—the kid—in the corner by the bathroom and ignored me for most of the evening.

More recently, in Orvieto, Italy (as I started my research for this book), I arrived at a restaurant at 6 p.m.—long before any self-respecting Italian would ever show up—and shakily announced, “Per una, per piacere.”

“Per una?” the handsome waiter asked incredulously. “Perché? Sei molto bella!” I smiled weakly. Beauty had nothing to do with it. And, yes, I wished it was “Per due, per favore,” but it wasn’t. Italy is for lovers: per due. The waiter was overly attentive, which was only slightly better than being ignored: His doting highlighted my solitary state for the handful of tourists also eating at that early hour. While the bucatini all’amatriciana was prepared to perfection, it was overshadowed by my self-consciousness. I never made it to dessert.

Fast-forward three years, when I, somewhat reluctantly, booked a table for one at a highly recommended cevichería in Lima. It was my only meal away from the demands of the presentation to which I’d committed, and I wanted it to be good. Nothing had gone as planned with the work gig: I had spent 28 hours in transit in order to spend 51 hours in Lima, and the speech I had labored over for two weeks was edited down to one minute. I needed a break—and I wasn’t going to settle for room service. Today, I will drown my sorrows in a pisco sour, I wrote in my diary.

I arrived with high hopes and an empty stomach to the restaurant El Mercado in the Venice Beach–like neighborhood off Avenue Hipólito Unanue. It was beautiful in a rustic-industrial, hipster sort of way. I walked through the wooden entryway, past the long line of people with- out reservations, to the small table where an affable brunette hostess stood. She smiled, checked off my reservation—and ushered me to the worst table in the restaurant, right next to the drink station with a view of the sink. I withered and shook my head. “No.”

“¿Cuál es el problema?” the hostess asked. “No. Imposible,” I said. I wasn’t going to settle. She raised her hands and swept them around the restaurant. “Es lo que tenemos.” It’s what we have. I followed her gesture with my own, jabbing in the air at several open tables. She tried to explain they were for bigger parties and suggested a seat at the bar, explaining I could eat the full meal there.

“No.” I was holding firm. I could clearly see there were better two-tops than what she had offered. My table for one would have to be better. She gave me a “Well, you can leave” kind of shrug and turned her head back toward the line of people queued in front of the hostess stand. I felt a little betrayed by the absence of sisterhood and felt myself starting to judge her acid-washed jeans. But then I stopped myself, smiled and said, in horrifically mangled Spanish, “I am a journalist writing about food. I made a reservation weeks ago. I called from the United States. I want to be here.”

She sighed—and relented. “Sígueme.” Follow me. She led me to the beautiful, upholstered area in the middle of the restaurant that had three vacant two-tops.

This small victory was a defining moment for me because part of this journey has been about remembering who I am and what I deserve. I deserve a nice table for one. We all do. It seems obvious, but it’s a lesson I’m still learning.

People are often incredulous that someone who has traveled all over the world sits in her room and orders room service.

I do. I did. Now I go out. The waiter was patient and kind as I fumbled through my order.

I asked, in Spanglish, for half portions of three of the best dishes on the menu—ceviche, tiradito (raw fish in a spicy sauce) and pulpo (grilled octopus)—plus the signature drink of Peru, pisco sour. He assured me I had chosen well and would enjoy it all.

“Sí, verdad,” I replied. “Everything is new to me. I will enjoy it all.”

No sooner had those words come out of my mouth than I realized I had changed. I was no longer apprehensive. I was now actively moving toward the unfamiliar—not out of a sense of sensorial or journalistic duty—but because I was excited to.

Twenty minutes later, the waiter returned with three mouthwatering dishes, but one, in particular, captivated me: A small eight-tentacled, deep purple wonder, the octopus was gorgeous. Cooked over fire, it was served with grilled mushrooms, small tomatoes and capers. A few days prior, I had eaten what, until that point, was the most delicious octopus of my life at a wine bar in Charlotte, North Carolina. That octopus had been slightly rubbery, made tender by a quick steam in a pressure cooker. This one was the opposite, with flesh so tender I could cut it with my fork. The dish was slow and deliberate. It tasted of wood and the ocean—the very essence of pulpo. It made the defeats of the day and discomfort of dining alone worth it.

It made me cry.

Italian scientists from the University of Naples have discovered that when we eat for pleasure, rather than solely for hunger, the reward circuit in our brain—that primal neural network that fires when we win a prize or have an orgasm—is activated. This reinforces our desire to reach for foods based on how they taste, rather than strict caloric nourishment. It is a desire that, literally, transforms how we receive food. In one study, clinical nutritionist Leif Hallberg and his colleague at University of Gothenburg in Sweden found that people absorbed significantly more iron from food, even when roughly the same amount of iron was available, depending on the composition of the meals.

This was evident in the pulpo. It had been made carefully and was a significantly different experience from other octopuses I had eaten. Like my cup of Yirgacheffe coffee, the octopus invited me to pay attention and savor.

What is essential isn’t limited to nutrients. What is essential is what gives us pleasure—and from where we derive meaning. Food transcends the mundane and interweaves the disparate. It reminds us of our interdependence. We are what we eat, and we eat what we are.

With each bite of octopus, tears welled up in my eyes. I couldn’t stop them, but trust me, I wanted to. I definitely didn’t want to be the weird single lady in the middle of the restaurant crying over a plate of food.

My tears were mostly about the exquisite taste, but some small part of those tears was made of the sad acknowledgment that, for years, I had been depriving myself of this. In city upon city, I had chosen to sequester myself away, dining on room service and takeout, waiting until one became two.

Not anymore. No más.

When had I become someone who cared so much? This person who, through daily cups of coffee and occasional plates of octopus, started to see both the world and myself in their composition? When did my reflection begin to show up in the glass of wine? As my pisco sour buzz set in and my tears waned, I started to realize this evolution was always happening. Only now, I was paying attention. Our tastes, our food preferences, our environments, the flora in our guts—they are always changing. Change is the constant, and when we become conscious of it, something amazing can happen. We can shape it and love it; we can make it our own.

We, the eaters.

Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of the Foods We Love (published by HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, Copyright 2015) is available wherever books are sold.

*Editor’s Note: Here at elephant, we’re notorious bookworms—we love them, and want you to love them, too. But, recently, we found out books are evil—one of the worst things for the environment. Before you buy your next book, read this and this. Keep reading, but read responsibly.

Author: Simran Sethi

Photo: Author’s own / Book cover

Read 0 comments and reply