When I got married, it was tempting to post a photo to Facebook and instantly broadcast my news to all my friends in one single upload—but in the end, I posted nothing.

Most of my friends didn’t know I was getting married, nor did they know I was engaged.

Many of them didn’t even know I was madly in love.

The wedding took place in Las Vegas on the 29th of February, a day that falls once every four years. It would, no doubt, have been the most popular Facebook post that had ever been on my wall. I was seduced by the promise of hundreds of likes, and I almost clicked the share button—but then I didn’t. I started to question my relationship with technology.

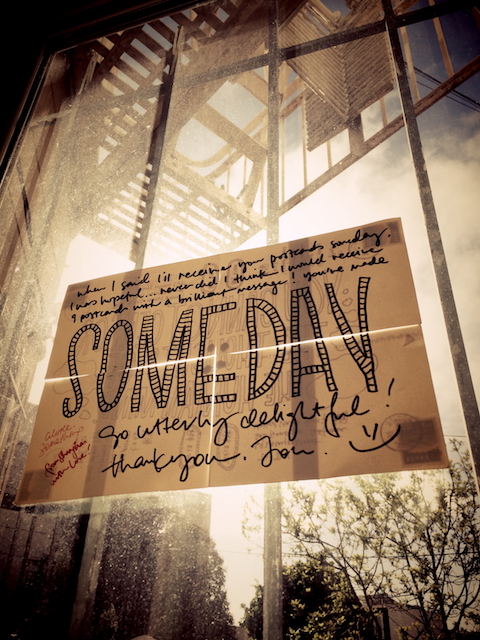

My wife and I began as pen pals, brought together by a shared experience of living abroad. She told me, “It would be nice to get something from you someday.” I sent several things and they never seemed to arrive. Eventually, I managed to get nine postcards to arrive in her mailbox. I had written a message across them that she could only read when they sat side by side. She replied across a canvas of four postcards, concluding: “You made my someday.” Junk mail aside, she has been responsible for the majority of what lands in my mailbox.

I tell her often, “I fell in love with your handwriting first, and then I fell in love with you.”

Technology is incredible. The relationship between my wife and I would not have survived without Wechat, a China-based messaging app. I use Skype frequently. Facebook is essential for me to keep in touch with my friends. Technology has had a significant impact on my life.

That said, I worry that we underestimate the importance of the traditional correspondence of voices, faces and handcrafted words. I worry that our society is optimising its technology for laziness at the expense of something greater. Why call twenty people when you can tell them together instantaneously, and get twenty likes in the process?

With the current trend in technological advances and the world becoming more cosmopolitan, is there not a danger we are being conditioned in such a way that we are losing something that cannot be recreated with Helvetica and Arial? I’ve learned that not all news is Facebook worthy. I’ve missed a marriage breakdown and a death.

Seneca, the Roman stoic philosopher, an avid writer of letters, wrote two-thousand years ago to his young friend Lucilius about the importance of handwriting:

“…the handwriting of a friend affords us what is so delightful about seeing him again, the sense of recognition.”

Like many others, I’ve cared about how many likes the things I post on social media get, and I’ve gone to great lengths to get them. I’ve straightened photos and added filters. I’ve even, at times, felt jealous that others on Facebook seem to be able to command more than 200 likes and that I’ll never be so popular.

Our fascination with likes could be for many reasons—for me, they’ve been a sign that the things I do are acknowledged by others. They’ve played to my insecurities, as being abroad, far apart from friends, I’ve wanted to stay close to their hearts. Likes were a signal that I was still relevant, a reminder that I was still in their thoughts.

Recently, I witnessed the death of a man in a car accident. After the event, traumatised and in shock, I reached out to my friends on Facebook. I got dozens of comments, but in reflection, all I truly needed was one phone call.

For my marriage, something this important, I wanted more.

I recalled that feeling of excitement when I saw my handwritten address from my now wife and the joy of reading her news in detail and replying to her at length. I wanted to attempt to give that feeling to others. I wanted to feel something less hollow than a thumbs up in return.

I relinquished hundreds of likes by not sharing my wedding on Facebook. I have no regrets about this decision. Rather than counting a number and reading commentary from everyone I knew in a single Facebook post, I connected with them one by one.

I gained the ability to tailor my message. To some, I spoke to why it happened without them—a British citizen in the United States and a Singaporean in China would have had a logistic nightmare on their hands. I was careful to reassure my oldest school friends that I would have had three best men as I wouldn’t have been able to choose, but all they cared about was when the belated stag party was! My grandfather and I spoke about the service and the reverend—he wanted to know all about him. The friend I told once “I will marry this lady” and who had told me to go visit her in China, was so thrilled to know that I had been right and she had played a part.

My wife and I gained the ability to connect more deeply through our news. We have shared the details of our marriage over meals, private message exchanges, games of pool and plentiful telephone calls. We could hear their surprise as we told them over the phone. We could sense their happiness as they instantly typed back in a private message exchange, or rang with single word questions as greetings. We could feel their love and excitement.

In our conversations, we answered the same questions again and again, but each time we did this we got to relive our magical happy day. We have dozens of dinner and drinks invitations. We unexpectedly got lovely handwritten letters from people we hadn’t even told. As a result, we felt more connected to our friends than ever.

Will we have another service? No. My wife made the grand suggestion that we should meet every individual friend privately to tell them about our day in person. There are still many people in my own world I need to share our news with, and now there is a new list of friends belonging to my wife who I am excited to grow close to.

We’ll use technology to have those conversations for sure, but it will only be a means to an end, not an end in itself.

Author: Jon Robson

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Author’s Own

Read 5 comments and reply