“Stop thinking about saving your face. Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story. Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon’s hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly – once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try…tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe, what to fear…Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.” ~ Toni Morrison, The Nobel Lecture in Literature, 1993

~

It’s day five post-chemo.

Eva’s body has reacted as if she has been taken over by some sort of super-virus.

She moves slowly and carefully. If she moves too quickly, she becomes “woozy”—the word she keeps using to describe the sensation of fullness, dizziness, vertigo, heaviness in her head.

Her appetite has slowed to a crawl, but she keeps putting fuel in to her body. Her taste is changing: wine and coffee and chocolate are not what they were a week ago. Her hip bones are starting to ache, probably from the injection she had the day after the chemotherapy, the turbo-boost to the bone marrow in her long bones and hips to start pumping out white blood cells. And she is tired. She did little but sleep for four days. She would come in to the living room at times to interact with the children.

The last three evenings she has felt somewhat better but the last two mornings were disappointing. This morning she lay on Mia’s bed as Luca did bum shuffles, commando crawls and rolls around the floor. I asked her how she was and she said that she feels like her life has been taken away from her at the moment.

She feels like she has lost control; even looking after an eight month-old baby feels overwhelming on these days.

We decided to get out of the house for the first time in five days. We set off on the less than 10 minute walk to the village. We were slower than usual. Fortunately it was cooler today than it has been and once she was moving she started to feel a bit better.

We went to one of our favourite cafes, where the owner came out and gave Eva a long hug. Just before we left she came back and pressed something into Eva’s hand with her phone number on it. Like so many other incredible people, she insisted that we ask for help when we need it. She said there were some vouchers for the cafe in the bag (which made me well up).

We walked away, buoyed by the visible signs of care and affection that people are demonstrating toward Eva (and by extension, our family), which made me cry properly. I haven’t cried for about a week, so that’s good.

We always head to the sea at difficult times. Eva and I virtually ran away from our childhoods and teenage years to the sea, where we lived and worked on a ship for two years. The sea was a haven and a learning ground. There’s nothing like having nothing but thousands of miles of ocean around you to force you to orientate yourself in the world. Today, we went back to the sea again—just up to our ankles at our local beach, but there is a timelessness and changelessness in it which grounds us.

Eva said a couple of times that she has felt like she is “fading out” of life, or becoming irrelevant in some way. I interpreted this as an expression of the extreme exhaustion and discomfort. But there is also a clear change in roles for both of us.

Eva was a full-time, stay-at-home mum looking after a baby and a pre-schooler, who may have considered going back to work as a teacher in a year or two. I have gone from being a doctor working full-time for a busy public mental health service, to becoming a full-time, stay-at-home dad and carer. Eva has gone from being a super-organised, energetic and involved mother, to some days, being barely able to lift her children, or spend any extended amount of time with them. The vocation which she had just chosen to invest her life in full-time has suddenly become unavailable to her.

The story of our family is changing day by day. The next 12 months looked quite clear to us before. We were approaching some milestones and markers. We spent time imagining what life would be like with one child at school—how she would change and develop.

These things are still going to happen, but our perspective has changed considerably. Life could change in the blink of an eye. Even though I did not think I was immortal or indispensable to the universe, I have somehow just started to realise this.

Our family story, the narrative of our life, has hit a hump-day. A hump year? We are not unique in this, but this is our story. Can we create it, still? Has the pen been taken from our hands so that we can’t determine much but attending appointments and organising care for our kids when we have to be at a hospital?

“Narrative is radical,” says Toni Morrison, “creating us at the very moment it is being created.”

We know we are being inexorably changed by this chain of events. It’s a change that has been forced upon us, and mostly upon Eva, and not something we would have asked for. But it is something that we can still be creative with.

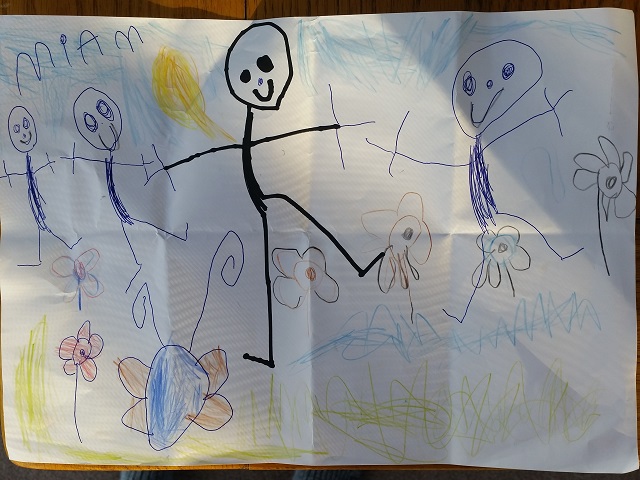

Our fears for how this could affect our children are tempered by the hopes of what this will teach them, especially our daughter. Will she learn to be kind to herself when she is unwell or struggling or low in mood? Will she learn to be caring toward others when they are scared and unwell? Will she look back on her childhood and be thankful that her parents demonstrated one way of dealing with a major adverse life event?

Will she learn from a mother whose confidence and self-worth and value goes much deeper than her physical form? Will she learn that she is safe—as a person, in her own being, and within her family? Will she learn that when bad things happen, others are there to help and to hold and to encourage? Will she learn that in the bigger picture of the world’s suffering, her kindness and courage is enough to make a difference to individuals’ lives?

Maybe we can influence this story still.

We are early on in this new trajectory in our narrative. We’re feeling our way amidst the psychological and physical effects of breast cancer and its treatment. We are trying to manage our own mental health, and deal sensibly with the difficult emotions and sensations that it gives rise to. We are learning what different days are like and what we can expect of ourselves, of our spouse, and of our children, when we all are tired and stressed—and when we are joyful and relaxed.

“The scariness of things with no names” is the monster we are struggling to contain. The unknown. The unforeseeable. Facing it demands vulnerability.

We need others’ love and support. We need psychological transparency with ourselves and one another. This vulnerability is fearful, and goes against the instinct of self-protection which we are primed to hide behind when life becomes too much. And writing is some manifestation of that for me.

I don’t want to psychoanalyse too much why I am displaying this vulnerability for others to see, but I think it originates from some fundamental belief in the necessity of human connection, and a strong hope that people are kinder and more thoughtful and more loving than we would sometimes fear to believe.

My experience of this over the last almost few weeks is that they are.

I hope that if we can tell each other what the world has been to us in the dark places and in the light is, our common vulnerability may be a force for healing and hope.

~

Author: Simon Menelaws

Images: Author’s own

Editor: Khara-Jade Warren

Read 2 comments and reply