Meditation is a magnificent tool practiced for thousands of years, across dozens of cultures, by millions of people.

But a tool for what?

What’s the problem?

Why should I meditate?

If you wake up in the middle of the night in total contentment, survey your life with complete satisfaction, and find yourself stress-free, then maybe you don’t need meditation.

If you don’t have a question there’s no need for an answer.

The first step in solving a problem is realizing there is one.

But if you’re young and stressed about school, getting a job, or being successful, then meditation can help. If you’re older and worry about your kids, your retirement, your relationships, or the economy, meditation can help. If you’re anywhere in between and trying to find more meaning in life, to live it more fully, to be more focused, or to discover real happiness, then meditation can help.

People today are hurting. The litany of personal, social, and global problems is obvious.

While meditation can help with these larger issues, it’s meant to help us with our personal ones. When you get down to it, global problems are by-products of personal issues. People, not the physical world itself, cause most of the world’s difficulties.

The Christian philosopher Blaise Pascal said: “All of man’s difficulties are caused by his inability to sit, quietly, in a room by himself.”

Our journey will take us to the root of our difficulties, and show us how to sit quietly by ourselves to remedy them.

On an individual level, there are many sources of discontent. You’ve probably heard them all. One of the most noticeable, and unsettling, is the epidemic of distraction, busyness, and speed. Emails are popping up constantly on our iPhones, droids, and laptops.

They often spawn a sense of urgency—I need to read it and respond now. Text messages ping into our awareness endlessly, commanding an instant reply. Facebook and Twitter are conquering the world, and our attention. Information is hurled at us from every conceivable direction, and at speeds that are reaching escape velocity from reality.

The result of this relentless barrage is people like you and me. Innocent folks who are being drawn and quartered by the dark side of this information age. Our minds are being torn apart and scattered in all directions as we struggle to keep up with a world that is running out of control. We’re losing touch—with ourselves, with others and with reality.

Tools that are designed to connect us (the social network, the World Wide Web) pull us away from human contact.

How many times have you seen people at a dinner table relating more to their devices than to each other? How often have you been distracted while reading this chapter?

Gadgets made to simplify our life are making it more complex. Smart phones are dumbing us down. Every new upgrade serves to downgrade our attention span. Convenience has turned into a bill of rights, and instant gratification is virtually law.

A recent study at Carnegie Mellon showed that the distraction of an interruption made test takers 20 percent dumber. That’s enough to turn a B-student (80 percent) into a failure (62 percent).(3)

Even the names given to the contraptions of this information age, which is also the age of interruption or distraction technology, hint at the problem. “Droid” (the smart phones that aren’t iPhones) is short for “android,” which means “an automaton in the form of a human being.” “Twitter” means “to talk lightly and rapidly, especially of trivial matters” and often instills a “state of tremulous excitement.” “Facebook” mostly delivers face value, and struggles with conveying depth. “Surfing” the web denotes skimming across the surface of things; the internet and world wide web imply getting caught up; something going “viral” suggests a rapidly spreading infection; iPhones, iPads, iPods, iTunes, iMovie, iChat, and iCal are all about “I,” not you.

And all these flat screens depict a superficial life with the ultimate depth of a pixel. It’s a perfect symbol of how the information age is screening us from life—and making everything flat.

Our speedy and splintered lives are like a stone tossed across the surface of a pond. We skip from one bit of information to the next, as fast as possible, with no ultimate goal in sight. We’re glancing on top of life, going nowhere fast.

And we’re outsourcing our mental capacities to slippery silicon chips, then wondering why our personal lives don’t compute any more.

One of the biggest problems is that we confuse information for experience, and end up existing in a virtual world. We live in our head and not in reality. The clinical result of this speed is what professionals call continuous partial attention, attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or any number of infections of attention. We’re neither fully here nor there. Below this surface diagnosis lurk depression, anxiety disorders, and a host of deeper problems.(4)

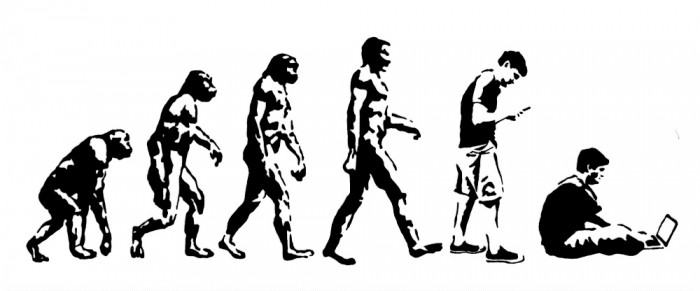

The opposite of evolution is devolution, and distraction is at the heart of that treacherous regression. (See Figure 1 below.)

We’re choosing information overload, divided attention, and multi-tasking, and losing our ability to concentrate, contemplate, or introspect.

Thoreau referred to the technological marvels of his day as “improved means to an unimproved end.” How much more “marvelous” are these modern gadgets, and how dramatically unimproved is the end today? These technological marvels are often nothing more than weapons of mass distraction, and just as destructive as their military counterparts.

The personal result of distraction and speed is a gnawing feeling of dissatisfaction, anxiety, and loss of meaning and purpose. There’s a sense that something is missing. Life feels incomplete. As we will see, something is missing. But it’s not out there. What’s missing is in here. Our attention is missing. We’ve gone AWOL on reality. We’re all MIA—missing in attention. As the song says: we’re looking for love—and happiness—in all the wrong places. It’s such an irony: our inability to be fully present (in here) is what generates the sense of absence (out there)—a topic we will return to in detail.

There’s no shortage of bad news. We all know it. While there’s no need to harp about it, there is a need to identify it.

Without a proper diagnosis we’ll never find a cure. We’ll continue to speed along with everybody else, feeling the pressure to keep up, and find ourselves more and more dissatisfied. I rented a U-Haul truck the other day and right above the speedometer was this safety message, a lesson that applies to all of life: “Speed kills. Slow down and live longer.” Mental speediness—the zoom zone of the modern mind—kills the deeper experience of life. Slow down and live more fully. Reboot your soul into silence and stillness.

Studies have shown that many people are turning to drugs or alcohol to manage their stress.(5) Others are turning to entertainment, or infinite forms of addicting distraction (addiction itself is a form of distraction). Perhaps one solution is some digital detox. Perhaps the best solution is to temporarily drop out. Not out of life, like a hippie, but out of our busyness and speed. Take a few minutes to drop out of each day and into a peaceful state called meditation.

Take a break. Stop skipping across the surface of life and you may find the depth that you seek.

You may find what’s missing. Stop and drop—into the magic of meditation.

Without taking an honest look at our lives, and the suffering of others, we tend to grow numb and complacent. So many people are insensitive—literally and figuratively out of touch—with themselves and with others.

Because they spend so much time in their distracted heads they’re losing the ability to feel, and to empathize. Perhaps it’s because things in the real world are so bad that we take refuge in a virtual one.

It’s so easy and tempting to check out of reality and into a flat screen—either a literal one, or the screen of our distracting thoughts and fantasies. But if we continue to check out and the world will continue to go viral.

And we will all merrily skip our way into personal and collective hell. Distraction doesn’t just kill the full experience of the present moment—it literally kills. How many times have we heard about some tragic accident because a driver or pedestrian was inattentive?

How many times a day do we bump into things, physically or psychologically, because we are mindless? All these small accidents are ominous warnings of the impending larger ones.

Distracted people don’t notice things. They don’t perceive the clear and present danger because they’re not present for it.

As the poet Rumi said, “Sit down and be quiet. You are drunk and this is the edge of the roof.”

~

References:

3. See Brain,Interrupted by Bob Sullivan and Hugh Thompson, in The New York Times, May 5th, 2013.

4. For example,studies have shown that those with ADHD have much higher rates of criminality and drugabuse. See Paul Lichtenstein of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, quoted in The Denver Post, November 22, 2012.

5. See Managing Stress: Principles and Strategies for Health and Wellbeing by Brian Luke Seaward, Jones and Bartlett Learning, Burlington, MA, 2012.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: David Blackwell at Flickr

Read 0 comments and reply