Has anyone noticed the, “30 things you must do before turning 30,” “15 tips to improving your yoga practice,” and “50 ways to get better in bed,” trend?

Self-improvement prescriptions. Like the kind your dentist gives you: 1) Floss 2) Cut soda 3) Come see me again in six months (Obama Care permitting).

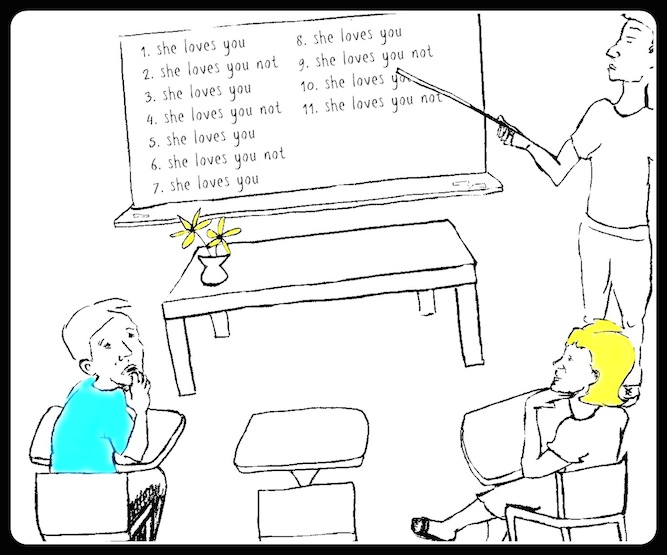

Except, unlike dentists and doctors’ instructions which communicate a few tried-and-true items to remember, self-improvement lists are subjective (while sounding misleadingly authoritative), over-simplifying issues and creating more social media buzz than genuine, life-altering support.

It’s no surprise that in our digitally charged insta-info world lists are trending. I’m fighting the urge to make this article, “10 Reasons You Should Give Up Lists.”

Lists are an easy way to organize. They are quicker to both read and write, obliterate tedious transitions, encourage succinct arguments and reduce time weeding through words. Lists are essentially outlines, which appalls English majors (our hard-earned skills of “smoothing flow” can’t be obsolete!?) but satisfies the average online web surfer.

Lists are, in short, information porn.

And there’s a time and place for them: quote collections, contest winners and recipes. Lists are useful to convey simple, uncontroversial commands: 1) Stop 2) Drop 3) Roll, or to propose utility: “16 Ways to Use Apple Cider Vinegar Every Day,” or in a manifesto: “Five Reasons We Should Be Naked Right Now.”

But lists are detrimental to our self-confidence, attention spans and interpersonal relationships when they advocate a radical life shift, unsupervised personal problem-solving or anything categorically self-improve-y.

Yet self-improvement lists are understandably popular in part because they propose seemingly instant, attainable solutions: “10 Ways to Make Him Fall in Love With You Again,” or “Eight Steps to Happy.”

While self-improvement lists make difficult problems seem surmountable, they also, out of practical necessity, overgeneralize. This universalization can result in readers failing to actualize bullets based simply on individual differences.

After enacting, “25 Attitude Shifts to Make Your Hair Bounce Like Taylor Swift’s,” or “25 Ways to Curb Your Enthusiasm,” we often find ourselves still, or back, at square one—flat haired and angry. But we got to #25?! When the quick-fix solution fails, we’re left feeling incompetent and inadequate.

Self-improvement lists then disguise their remedies as lasting solutions, sanctioning band-aiding over real healing.

These faux answers are misleading, and even dangerous. If I’m considering suicide, “25 Ways to Be Happy Again” prefaced by the picnicking model picture is useless; I need professional help. Solutions to matters of the self often can’t be found on the Internet, but rather by calling Mom and crying it out. Or writing it out. Singing it out. Sweating it out. Sexing it out.

Pick something, one thing, and get off the couch. Efforts to become our best selves require sustained strength and heart; there’s no one-size-fits-all recipe.

These lists are also deceivingly attractive because their easy-skim format condones troubleshooting our deepest darkest problems while simultaneously [insert five other tasks here].

The average Internet user peruses article titles, headings and pictures while texting, listening to music, holding a conversation, eating and working. Lists provide easy information ingestion, which makes us feel productive but actually only further scatters our minds and divides our attention.

Thus in appealing to our attention deficits, lists also enable them. Ironically, it’s usually their authors that advocate #506) Get comfy with a book in the a.m. and resist your impulse to jump on your computer or do multiple things at once.” But their list is quantifiably successful because their reader is doing just that.

Lists replace time we could spend getting better at something, refining our attention or, perhaps most importantly, developing our interpersonal life. Like porn, self-improvement lists are composed by “professionals” but devoid of authentic, affirmative relationships. And the mere fact that authors don’t know us not only makes us feel anonymous and hollow but also vastly limits their capacity to help us.

In addition to lacking personal interaction with us, many of these self-professed experts lack actual expertise. Appearing as commandments, lists give authors an inflated image of authority, even though their sample size most often consists of one—the authors themselves. And writers are usually people like me, not the Dalai Lama; their two-cents is not the Magna Carta.

In fact, authors tend to be drawn to topics they struggle with. Should we really believe that the yogi writing on mastering utkatasana likes, or particularly excels, at utkatasana herself? Nevertheless, her perspective is valuable. But an essay explaining her journey would be more honest and helpful than a list of commands of which she herself has half-mastery.

Thus while lists facilitate a convenient, even deceptive, pass over the author’s own relationship to a given topic, personal essays capitalize on authentic experience.

For example, if I’d written, “10 Reasons You Should Give Up Lists,” I wouldn’t have shared the humbling fact that, until recently, I was an obsessive list-writer and bullet-er. I compared dog breeds on ruler-drawn spreadsheets fit for data validation when I was eight; I presented my parents PowerPoints of my desired wardrobe before middle schoolers knew what Microsoft Office even was.

My adolescent self-approval hinged on how many items I could check off in the mini notebook on my bedside table; even now, I combat the urge to record my every thought and task on my too-convenient iPhone.

It’s taken me awhile to discover that lists can artificially compensate for a deeper lack. When I’m most furiously devising lists is when I feel most listless: purposeless, insufficient. And I read self-improvement lists for the same reasons I write them: to give myself a sense of productivity and competency to change.

At what point does our to-do list substitute our search for deeper meaning and relationships? The possibilities proposed by a list are precipitated by the premise that what we’re doing right now isn’t enough. The implication of self-improvement more broadly is that the present self needs to be improved.

If we stopped reading about how to be happy, the steps to making our square face sexy in pictures, the instructions to emulating such and such Harry Potter character or guru, perhaps we’d arrive at ourselves, just as we are and good enough.

In short: Let’s share our stories, expand our capacity for empathy and learn from one other, not tell each other more to do.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Travis May

Image: Author’s Own

Read 0 comments and reply