One day my friend, Joan’s, husband had an episode of numbness on the right side of his face and the next day he was dead.

It really didn’t happen that fast, but it seemed like it.

A few weeks before he died, he’d mentioned that he’d had some slurred speech as we sat chatting in my store where both he and his wife worked for me.

I’d had nothing to go on except a shock of intuition when he told me that the doctors were checking for a stroke, and immediately thought to myself that it wasn’t a stroke. It was brain cancer. Turned out I was right.

A month later Joan called and asked me to go over her husband’s obituary with her. I suggested she come to the house for dinner so we could put the draft on my computer and make all the changes right then.

During dinner, Joan leaned over the table towards me and, pointing to her breastbone, told me that she had been having a pain in her chest. Unconsciously, I pressed my fingers to my own breastbone.

“Yeah. Right there,” she said.

She had an appointment with her oncologist in a few days. Maybe it was back, she said. Maybe her cancer was back. Not wanting to hear that I told her it could be grief.

“Grief can hurt too, you know. Right there in the same spot.” I knew from my own experience that grief can lodge like a needle in the breastbone.

But Joan placed her hand against the side of her rib cage and told me she had a pain there, too.

I walked around the patio table and went over to Joan. She turned slightly and I put my hand on the sore place on her rib cage. Under my fingertips I could feel a lump there about the size of a walnut.

When I spoke with Joan a year later on the phone her voice was weak, watery. There were no more meds for her to take. She was losing weight, was unable to eat, was in constant pain and out of options.

I’ve heard the concept that we can “ripen into death.” That in some way, down deep inside, we know that we are about to reach that moment—that one and only moment and that we prepare ourselves for it. Is that what Joan had been doing since her husband had died? Had she been ripening so as not to fall too hard from the tree?

I thought of my father telling me the night before he died that he wasn’t afraid of the physical dying so much as he was afraid of the emotional aloneness of it. He didn’t want to be by himself when he stepped onto that strange and distant tundra.

I thought of a scene that ethnographer, Carobeth Laird, had written about in her memoir when she was near death after giving birth to one of her children. Her husband was weeping desperately at her bedside as he felt her slipping away.

“Don’t go,” he sobbed. “Don’t go.”

She raised her head from her pillow.

“You come too.” She whispered, “You come too.”

When I was on the phone with Joan I asked her if she thought that her husband was waiting for her.

“Oh yeah,” she said. She was sure he was. She’d been talking to him every day since he died.

Her exact words were that he was going to be there. “He was going to break her fall.”

~

Relephant read:

What Death Teaches Us.

~

Author: Carmelene Siani

Editor: Ashleigh Hitchcock

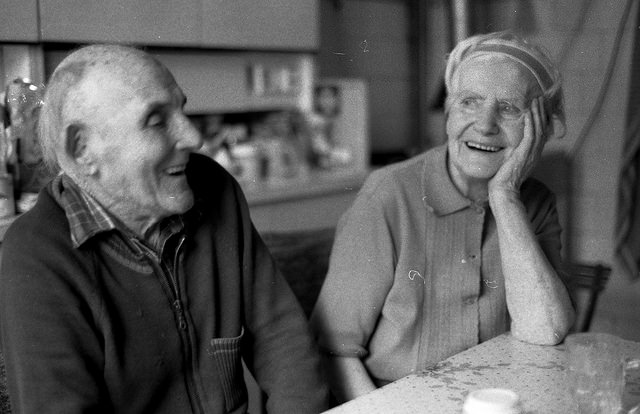

Photo: flickr

~

Facebook is in talks with major corporate media about pulling their content into FB, leaving other sites to wither or pay up if we want to connect with you, our readers. Want to stay connected before the curtain drops? Sign up for our curated, quality newsletters below.

Read 3 comments and reply