I don’t know anyone who has survived a sexual assault and reported that life carried on exactly as they had planned, despite the minor inconvenience of having their world turned upside down and their sense of safety within it utterly betrayed.

Thus, I never suspected that this would be my life. I could not have predicted completely forsaking my yoga mat for the couch and surviving vicariously through a computer screen like I did today: slamming back Diet Coke, still in my pajamas at six o’ clock in the evening, disheveled into emotional chaos but victoriously alive nonetheless.

Mindfulness in the aftermath of my assault means knowing when what is needed to nurture myself is a far cry from anything I’d do while practicing Ashtanga, and learning to accept that this is perfectly okay.

A true yogi knows when to get the hell off the mat and breathe into the true needs of the moment.

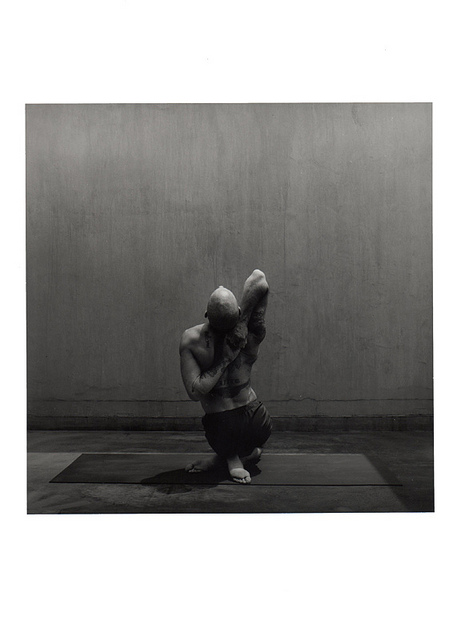

If you had asked me yesterday if I still considered myself a yogi, I would have balked at the suggestion that any of the practice’s joy and peace could remain within me. Practicing Ashtanga has always centered me unlike any other of my many attempts to soothe my rabid brain. The specific set and sequences of Ashtanga’s asanas provide me with a consistency I struggle to find in the upheaval of a daily life ruled by internal mental illness and external sociopolitical upheaval. It allows me an opportunity to celebrate my body and develop physical, emotional, and spiritual strength and peace because Ashtanga throws me no curveballs and, therefore, assures an arena to advance my practice with more ease and joy.

That is why I initially found solace in Ashtanga yoga when recovering from self-destruction and childhood sexual abuse in high school. It has since remained true to me, despite needing to take pause from the practice following a significant back surgery, but I never wanted to test the strength of these truths with as much desperation as I have following being victimized again in college. I doubted they were strong enough to hold this new level of pain I am experiencing in the aftermath, and yet they do.

Reconnecting with the spirit and practice of Ashtanga, slowly and gently, has reaffirmed for me the truths I found in it over two years ago.

The consistency of the asanas is again giving me safety when little feels safe, and I am relearning to nurture and celebrate the power of my body and the grit of my spirit with each reliable asana.

But it took me many months to trust myself to get to this place, to allow myself to bend into downward dog with the faith that I would not break. I believed myself to be completely trapped in the stagnation of my skeleton closet, which was not a comfortable living space (skeleton closets rarely are). Stories are not meant to be obscured behind vacuums and one’s humanity does not fare well when hung next to old raincoats, but because there was no eloquent way to say that it was still always raining trauma for me, the skeleton closet and I reluctantly signed a roommate agreement and settled in for the long-haul.

Today I told myself that it would be a good day. I did not bother acknowledging that assigning this pressure to myself does nothing of benefit for the struggle within; I’m well aware of that. At least, as aware as I can be with a mind that spends most of its time reliving exactly why skeleton closets exist for far too many queer people: they are places to bury our queerness so that our loved ones won’t have to bury our bodies. I learned this personally on September 4, 2015, when I was sexually and physically assaulted at my college because two of its other students didn’t approve of me. Despite the nightmare of their corrective rape, they simply could not fix what was not broken.

There is no getting around the fact that the assault has changed me forever. However, being profoundly changed is not synonymous with being irreparably damaged and doomed to disintegrate—unless I limit my understanding of the value of change to how well I am able to perform in its aftermath, which is how I framed the merit of my survivorship for months. After the assault, I deemed myself meaningless to society because I felt I could no longer interact with my community as a bodhisattva would. I also had absolutely no practical understanding of how to help myself. Despite how patiently I have been taught over the years to no longer hang myself or my potential from the gnarled branches of my family tree, I was completely unprepared for recovering from the effects of being sexually assaulted as an adult.

After being assaulted, I had to relearn how to hold my own personhood with the same dignity and respect that I am making my life’s work to champion in others. Ashtanga is helping me with that just as it did in high school, but I didn’t think even yoga could inspire in me enough resilience to recover from the emotional and physical scars left by my perpetrators’ hatred.

Though hopelessness may sound like a perfect assessment of my condition, I think grief is much more accurate. I was in mourning for the many aspects of myself that I felt my attackers had succeeded in killing that morning, and I mourned not being able to articulate the brutal and isolating process of grieving for those aspects of myself. But today, when I stumbled to my partner’s couch with my computer, I somehow tripped over the bodhisattva of myself and my grief shifted. The bodhisattva had been waiting patiently inside my skeleton closet with me all along. He held my grief gently as I sat for hours on the couch, exploring my story, delighting in the discovery that to be changed by tragedy is not at all to say that I have become one.

It is bizarre and astoundingly beautiful, the accidental rediscovery of a bodhisattva within oneself after an act of incredible violence and all that it can teach you.

For me, I found him through the blessed anonymity of the Internet (which my partner assures me is rarely truly anonymous, but it’s good enough for me), where I could share the victories, struggles, humor, support, and healing of my journey with others without experiencing either shame for the quality or guilt for the quantity of space I take up. I regained contact with my integrity by abandoning all of the pressures I placed on myself to be productive or composed and allowing myself the freedom to express truths and challenge lies however they were evident. I took myself as I was, and in so doing I found that I have even more to give to others. That, to me, is the buddha nature that outlives a massacre.

I began this piece by expressing that I did not ever expect this to be the state of my life. I absolutely didn’t, but not only because of the ways in which it has fallen apart. I am also amazed by the Ashtanga-like experience of putting it back together. Recovering from the hate crime in many ways parallels my experience of Ashtanga: It is a careful balance of boldness and gentleness, its process requiring the courage to be both flexible and strong. Balance is found even after having lost it completely and judgment is forgotten as the breath is remembered. Trusting the process of healing is like trusting the progression of Ashtanga, and though there are definitely more curveballs in trauma recovery than in yoga, I am relearning the consistency and reliability of my own strength and resilience as well as patience as I learn and practice the art of living.

Above all, I have become more than a tragedy: I have learned how to hold grief and meaning in the same pose and reclaim the bodhisattva within.

Author: Tristen Taggart

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Barry Silver/Flickr

Read 0 comments and reply