It’s been two years to the day since the love of my life ended our relationship.

We tried to make it work. We even went to couple’s therapy. I remember at our first session the therapist asked me what I was feeling.

I couldn’t get a handle on the question.

What am I feeling?

Was he talking about the Israel-Gaza conflict, or the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, or the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson? What about the random shootings that are happening on a regular basis? How about global warming?

I glanced at several plaques on the wall, diplomas and certificates, then I gazed into his eyes and said, “I need a context for the question.”

“How do you feel being here?”

“I’m here because I care about Melisa and I want to work this out.”

“But how do you feel?”

“You mean about the hundred and twenty-five dollars an hour it’s costing me?”

“What do you feel emotionally?”

I glanced over to Melisa, searching for an answer. She gave me a smile of encouragement.

“Emotionally? What’s that mean?”

I heard a sigh or maybe it was from outside. I felt the doctor’s eyes upon me, I saw my reflection in his glasses.

One hair curled out of his nose. I couldn’t take my eyes of off it.

“Do you feel happy or sad or fearful or angry or anxious?”

“I feel hungry.”

I had to drive to our second couples-therapy session straight from work. It was rush hour. Traffic stalled. I remember thinking that “therapy” was stacked against me. It was like diaper training. I didn’t want to do it. I wanted to shit on the floor and make you clean it up.

I felt manipulated, resentful, and ripped off.

I glanced at the clock on the dashboard. I was going to be fifteen minutes late, which made me feel better.

When I arrived, Melisa acknowledged me with a scornful expression, and this made me feel even better.

“What are you feeling, Tom?”

“Happy.”

At our third couples-therapy session (now I’m $375 into it) the doctor asks, “What are you feeling?”

“I feel like there’s something missing in my life. Even with the great sex, the powerful connection, and the intelligent conversation, there’s a subtle churning in the depths of my abdomen, like I’m drinking eighty-five-percent whole milk, missing the one-hundred percent pure.”

“Do you feel existential anxieties?”

“Existential anxieties? I don’t even know what that means.”

“The pains of human existence.”

“I thought therapy was supposed to help me, make me feel better.”

“But if it’s there, these feelings, it helps to acknowledge them.”

I closed my eyes and dove within. After a long pause, I said, “I feel the gravity of this body: the weight, the struggle, the decay, the transgression. I feel the body’s inevitable descent is in opposition to the cellular drive to survive—the opposing forces of a bad design, and under the surface, suppressed, and sublime, is the knowledge that the body will die. My days are numbered.”

From the clock on the wall, I heard the second-hand, twitch and click forward, twitch and click forward, twitch and click forward.

Melisa stared at the floor.

The doctor twirled the bottom of his beard, smiled, and said, “Very good, unfortunately, our time is up.”

That was the end of our therapy and my relationship with Melisa.

Here’s what I got out of it: I was alone and I was going to die.

For the next two weeks, I hunkered down in my flat with the drapes shut and the heat cranked up. I only ventured out for food or drink. I spent my time drinking beer, smoking pot, and watching Judge Judy. I ate Chinese for lunch, pizza for dinner, and an occasional Hungry-Man fried chicken for nostalgia, which had been swirling in my head.

I’d been nostalgic for the past week, which surprised me since I never had friends with whom to share memories of profound, or ecstatic, or heartfelt moments.

How could I be nostalgic? Nostalgic for what?

Perhaps I was more lovesick than nostalgic—or maybe I was nostalgic for another time, or another life, or for something I once knew that was now gone.

Finally, I pulled myself together and spent the next two years reading the Upanishads (Hindu sacred texts), which were so rich, I could only read a couple of paragraphs a day. At the same time, I studied Buddhist texts. When I wasn’t reading or contemplating, I meditated which quieted my mind and gave me a refreshed sense of peace.

I practiced yoga.

I was a peaceful Shiva warrior, radiating sun-love energy.

As I look back over the years, I was always practicing something or reading something or contemplating something.

I was always doing something.

Isn’t the essence of these teachings more about not doing than doing, more about not knowing than knowing—doesn’t fullness arise from emptiness?

If I’m already free, what am I practicing to be? How can I practice the truth of who I am?

I thought about stopping yoga and meditation and inquiry. If I just stopped and burned through every impulse to do something—what would happen?

But first, I’ll make popcorn and scan the babes on Match.com, then I’ll post something profound on Facebook:

Silence is the language of god,

all else is poor translation.

~ Rumi

Author: Tom Marino

Editor: Renée Picard

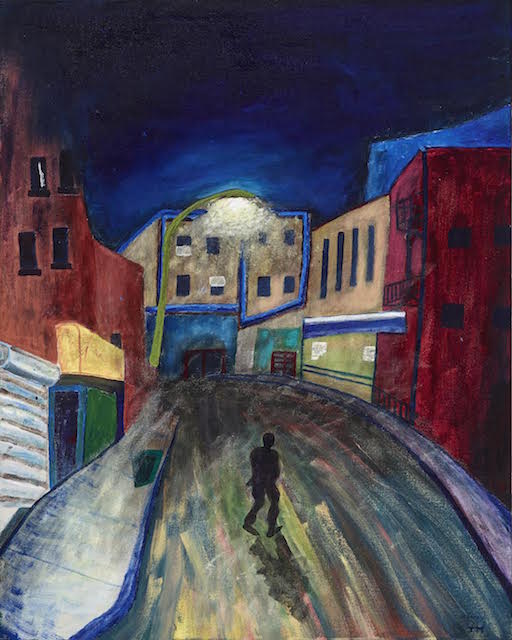

Artwork: Author’s Own

Read 1 comment and reply