“Writing the next Great American Novel?” asked a man’s voice through a half-whisper.

“I hope so,” was all I could think to say, glancing up at the sudden interruption.

“Really?” His interest seemed genuinely piqued as he came to a stop at the far end of the table where I sat. His face was mild and unthreatening.

“Well, not really,” I shrugged, “I just like to write. Maybe one day it’ll turn into something, but for now I’m just sort of collecting my thoughts.”

He nodded. There was an extended pause, so I smiled politely and looked back down at my laptop to find where I’d left off.

“Turn off the critic,” he said, still standing there when I glanced back up.

“Yeah…that’s the hard part,” I laughed.

“Write fast,” he added without hesitation, offering a solution to the problem he’d just presented.

Now, I was aware that this type of wisdom was either profound or completely generic. But for all I knew, he could have written the latest Great American Novel, so I decided to indulge him.

“Hmm. That’s a good point,” I said. I thought about how some of my best ideas roll out on the fly when my focus is soft, and I’m not chasing down inspiration. So I could see how writing fast might be a good way to outpace that inner-critic.

Still, I wasn’t entirely convinced. And the more I thought about it, the better I understood why. I happen to know that the critic doesn’t always show up as the clichéd voice who tells you your work is sh*t, and you shouldn’t waste another minute of your life trying to write something worthwhile. Sometimes, it does say that, but the critic can also be the voice of reason that keeps us anchored to reality—the devil’s advocate who challenges us to consider ideas from a new perspective. She reminds us to go back and examine our intentions often and sees to it that our words are an accurate reflection of them.

I didn’t say any of this out loud, but I had spent a lot of time thinking about my own creative process and have learned to give myself the time and space to let it develop naturally. So when he asked if I’d heard of process writing, my Type B personality revolted. But before I could say–-god no, please don’t make me cluster and outline—he was off to grab some scratch paper from the circulation desk.

When he came back, I tried to redirect the conversation.

I started off by saying that his advice had really caught my attention because it was a subject I had been fascinated with lately. I told him how I tend to think of the logical left-brain as the editor or the critic. And seeing as how language is more of a left-brain function, you can’t really get mad at it for showing up when you sit down to write.

“Still, the creative right-brain needs to be able to run free,” I continued, “Without the sensible left-brain breathing down its neck and constantly reigning it in.” I wondered if it was an inherent problem with any kind of work that combines logic and creativity.

I thought it was a pretty solid point.

He didn’t. He furrowed his brow and stared hard as if to examine me for mental illness. “You’re overthinking it,” he said flatly before adjusting his reading glasses and starting to scribble down some notes.

I looked on patiently as he walked me back through my ninth grade English class with all the brainstorming, clustering and Roman numerals.

Then he leaned in as if he were about to hand me the key that would unlock a lifetime of literary success.

“Why do you write?”

At this point, I suspected I’d better keep it brief. It was clear he wanted an answer that started with, “Because…” and begged no further questions. But it’s hard to summarize such a complex topic in just a few words—which hindsight has shown me would’ve been a perfectly good answer.

Then after taking a moment to think about it, it came to me: “Because I want to change the world.”

“Oh. I thought it was going to be something good!” he scoffed, shooting a playful smirk in my direction. If I didn’t know any better—and if it weren’t for the fact that he was of retirement age and not a 14-year-old boy—I might have guessed he was mean-flirting with me.

I chuckled reflexively, slightly amused by his sarcasm. I was aware that my response probably sounded as grandiose and self-important as it did naive. But knowing that it was none of these, I circled back to add some context.

In a self-conscious scramble to try and make my point, I started to think out loud about how the evolution of the written word had been both the seeds and the fruit of civilization; that it had been an incredible tool for self-discovery and self-expression.

But before I could finish my sentence, he was shaking his head as if he’d heard all he could take. “You’re trying way too hard,” he said, looking exhausted. “Just write. You don’t need to wrap it up in some big intellectual package. Forget all that evolution crap and just write.”

Hmph. “Well, I was until you sat down,” I thought to myself.

He peered at me from over the top of his glasses almost as if he’d heard my thoughts. “Sounds like someone spends a little too much time in their own head,” he scolded.

“Her. Her own head,” I thought.

Suddenly, I too was 14, and I couldn’t decide in the moment if my defensiveness was fueled by latent authority issues or if I was justified in my sudden contempt for this man.

What just happened? And who the f*ck was he anyway?

My face was hot, the air felt thick, and I had the overwhelming urge to flip him off under the table, a form of silent protest I found rather empowering in my childhood. But instead, I took a slow breath and sat there quietly nursing my wounds as he went on to tell me about a writing class he once taught at the state prison.

“You know,” he said, his brow still raised, “Some of the least educated men in that class wrote the most beautifully.” He continued, driving home his slam dunk with pursed lips and a look that said, “Take that smartypants.”

I tried to let it go. I am inspired by the notion that one need only a pen, paper and a story to tell in order to be an effective writer—that raw and honest expression trumps the false safety of pretense.

But wait. Isn’t that what I had been trying to express—that writing is about self-expression? Apparently, he hadn’t heard any of what I had said. Apparently, what he heard was pretense.

I left the conversation feeling defeated and misunderstood, replaying the exchange in my mind and wondering if there was anything I could have said that wouldn’t have been dismissed as empty rhetoric.

“Silence the critic.” I was tempted to take his advice.

But no. Writing, for me, isn’t about purging myself onto paper. It’s about cultivating awareness. That means listening when I don’t like the sound of what I’m hearing and searching for the truth in it, even if that truth might oblige me to make changes I’m not yet sure how to make.

It’s practice for recognizing the subtle difference between inspiration and distraction. Intuition and impulse. Honest self-reflection and self-doubt. It’s figuring out what to keep and what to toss out. One moment, one word, one step at a time.

See, writing isn’t about self-indulgence. It’s about self-mastery. And I think if any of us really wants to change the world, that’s a pretty good place to start.

Later that night, I sat down with an old college-ruled notebook and a blue-inked pen, fanning through it until I found a clean sheet of paper and drew a circle in the middle of the page.

Inside the circle, I scribbled the words, “Why I write.”

.

Author: Suanne Ringlein

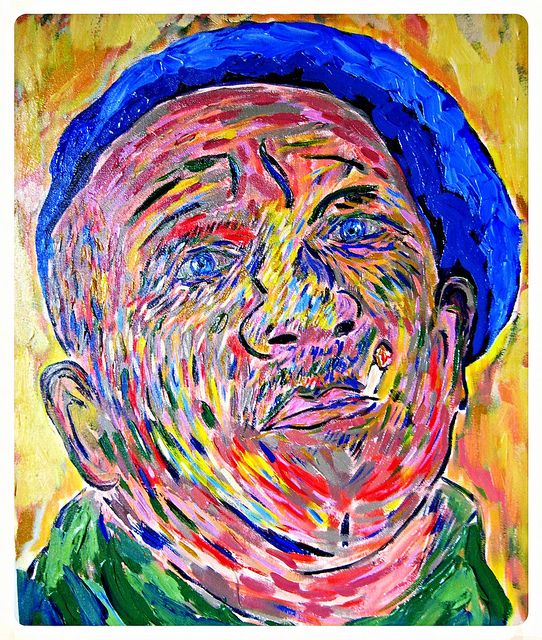

Image: Flickr/Steve Hammond

Apprentice Editor: Thayne Ulschmid; Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Read 0 comments and reply