These days, advice to “be in the moment” is served up more often than bean burritos at a Taco Bell.

The phrase is meant to refresh our awareness and return us to the here and now. But the lesson—uttered by every spiritual guru with functional vocal chords—has lost its intended punch.

The problem is that the idea of awareness has been confused with awareness itself. The concept has been analyzed, studied, and examined ad absurdum. Defining this state of mind, however, misses the point entirely. In fact, most of life defies description.

“We suffer from the delusion that the entire Universe is held in order by the categories of human thought,” wrote philosopher Alan Watts, “fearing that if we do not hold onto them with the utmost tenacity, everything will vanish into chaos.”

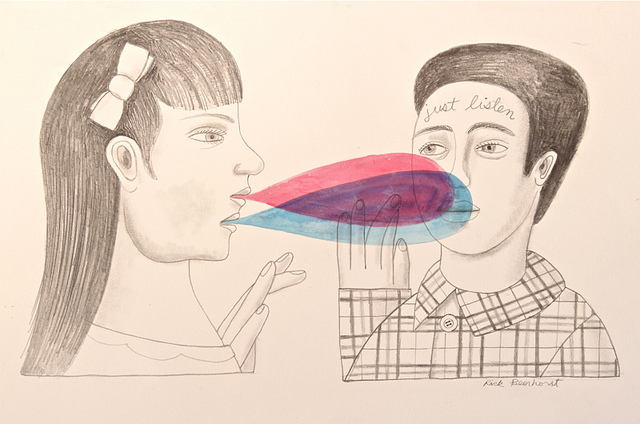

We trim down our experience to a handful of sounds we call words. This is, no doubt, useful for living in modern society. But it’s all too easy to lose touch with the reality these grunts aim to describe.

I’m not trying to play philosophical games. From birth, our thoughts are programmed with language. We learn to associate dynamic events with a few letters and a certain noise. The colossal expanse above our heads is simply the sky, and—with our minds caught in this concept—we grow oblivious to its changing colors, clouds, and tones. Raw experience, in this way, is filtered down to a single syllable.

Enlightenment—the goal of many spiritual practices—is a noise that causes particular trouble. It puts undue pressure on those who seek it. The confused devotee might sit for hours, wondering when this glorious state will come. This is not a mental pattern we want to cultivate.

We label emotions too. We quest after something called happiness, thinking there must be a readable formula for joy. But at the core, don’t we simply crave pleasant feelings? These moods, of course, can’t be talked about with any accuracy—only felt. Happiness is merely a word that’s useful for selling books.

The words “I” and “me”—powerful terms that fragment our present experience—deserve a mention here. Reality is, at base, impersonal. From moment to moment, thoughts, feelings, and sensations arise in consciousness. Then we label them “mine.” My problem, my ache, my itch. In this way, we identify and fix our physical and mental lives. Meanwhile, the real world keeps changing. We try, of course, to adapt. But we do this with the old, conceptual “me” at the helm. This is like trying to play Netflix on a VCR.

Let me reiterate: I’m not suggesting we abandon words. Language has allowed humans to collaborate and build civilization. It’s also handy when we want to get someone’s attention without making loud guttural noises. But if we never step away from the conceptual matrix, we’re neglecting a seething mass of instinctual wisdom.

There’s an ancient Buddhist parable that seems apt here. A man is shot with a poisoned arrow, and, as he bleeds out, a doctor rushes to his side. But before the doctor can remove the arrow, the wounded man wants to know the name of the fletcher. Then he’s curious about his assailant’s height. Then the type of feathers that adorn the shaft. The lesson is simple and direct: we are so absorbed in petty details that we can miss our life slipping away.

“Instead of having some particular object in mind,” counsels Zen legend Shunryu Suzuki, “you should limit your activity. When your mind is wandering about elsewhere you have no chance to express yourself.”

Limit your activity. This is Zen. The mind is most effective—and in a calm, “flow” state—when focused on a single activity. This practice also subdues our tendency to label everything with the proper noise.

We think too much, and these thoughts are constrained by language. We even think about thinking. Similarly, this article was my attempt to verbalize the problems with verbiage. It’s clear: thinking is not an optional activity. Yet if we don’t notice this compulsory habit, we’ll spend our lives distracted and confused. And a distracted mind, studies have shown, is not a happy mind.

But if we let go of words for a moment, maybe something extraordinary will happen. And this time, I won’t write about it.

~

Sources:

Suzuki, Shunryu, and Trudy Dixon. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. New York: Walker/Weatherhill, 1970. Print.

Watts, Alan. The Wisdom of Insecurity. New York: Pantheon, 1951. Print.

“A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy One” Scientific American.

~

Author: Brian Stanton

Images: Rick&Brenda Beerhorst/Flickr

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Read 13 comments and reply