For the past year, I have been engaged in research on a documentary series called “Urban Sutra.”

The series is about individuals and organizations who are harnessing the therapeutic aspects of yoga and using it in conflict zones as a transformational tool. They bring healing and reconciliation to communities traumatized by war, upheavals, and personal tragedy.

The film highlights a group of brave individuals—from places as far-flung as Colombia, Palestine, India, Kenya, Egypt, and inner city New York—who are dedicated to transform the world through yoga and meditation. These people bring the practice to those who need it most: the forgotten, rejected, and disenfranchised. These include maximum security prison inmates, inner city youth, addicts at drug rehab facilities, returning military veterans with PTSD, and Middle Eastern refugees.

Many people turn to yoga as a therapeutic modality after suffering some form of mental, emotional, or physical distress. Its effectiveness at alleviating these conditions is why it has proliferated rapidly the world over.

I too had found yoga at a particularly toxic phase in my life and it had helped me emerge from a period of darkness—the reason why the subject matter is especially meaningful and resonant to me.

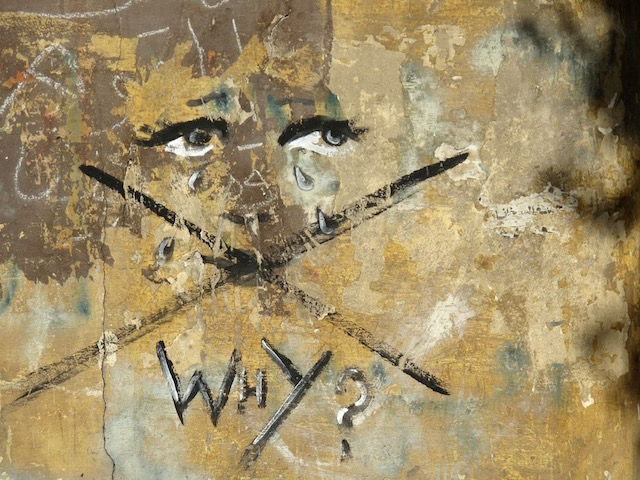

It was during the course of my research that I came across Mira Shihadeh, a Palestinian yoga teacher and artist living and working in Cairo, Egypt. She teaches and practices Ashtanga yoga, from the tradition of the Pattabhi Jois in Mysore, India.

In this wide-ranging and candid interview with me, she spoke about teaching yoga in the Muslim world, the intersections, and fault lines between yoga and religion, how yoga can be a catalyst for transformation in an increasingly polarized and fragmented world. We also talked about the ways in which this ancient practice can serve as an instrument of political and social change.

1) How has your religious-ethnic background affected the way you view and practice yoga?

I am Palestinian by origin, a product of the diaspora, and a U.S. passport holder, which means (until recently) that I can travel anywhere without interrogation. Well, anywhere but Israel, as I find the style of interrogation rude, irrelevant, and therefore stressful, as it would be for anyone trying to visit family or to explore their apparent “roots.”

I am Christian, yet I generally hesitate to say so since the majority of Palestinians are Muslim, and this seems to serve as a way to separate our people and therefore our cause. Like in India, being a minority is often used to separate a country’s societies in the government’s “war on terror” narrative. I am far more fortunate than many Palestinians who do not have the same opportunities as I have had in life.

What unifies us as a people is what will always be of enduring interest to me, but the responsibility of research into what truly divides us, from speech to action, needs to be urgently addressed, rather than shrugged off as “politics.” Extolling the virtues of “oneness” is not enough—it’s lazy. How can anyone experience true “oneness” without intimate knowledge of the dynamics of what divides us? True awakening implies a willingness to get one’s hands dirty; it means not caring for popularity.

2) Who are the people you teach yoga to? What difference has it made in their lives? Describe your teaching style.

I teach yoga to a wide variety of people. I strive to deliver it as an empowering collaboration between the teacher and the student, as long as there is enthusiasm. To me, it is a creative process: to feel present and to practice mind-body wisdom and awareness as a life skill. It gives my students a sense of how they can navigate the rest of their lives in their bodies.

Most of us are reluctant to be in the “here and now.” This is a survival strategy for stress and trauma: We have so much unlearning to do. As a student of psychology and now as a teacher of yoga, I feel I am truly working in a field I have been preparing for all my life.

The tragedy is that the mind-body connection is routinely severed through academic or scientific studies. I center my teaching on how wise our bodies really are, and what it means to actually “feel” and trust oneself. If we can only get a sense that we have been duped, we may be able to see reality in a clearer way; but many of us are too distracted for that type of reflection, especially modern day yogis from both India and the West.

Over time, and especially in the last few years, I devised a system of scholarship for traumatized individuals who truly need to learn empowering skills—especially with the recent crackdowns in Egypt on journalists, activists, lawyers, and any form of dissent.

My Shala is to me like a study in utopia, where the rich support the poor, the students who truly want to learn go far; and they are characteristically few. Like any Mysore program, the turnover is high and the student gets in proportion to what they can give in dedication. Questions of what “progress” is are often examined. We are researching life.

I love what I do, and I intend to remain a beginner student for the rest of my life—I always review what I think. There seems to be a price for this, but with time and experience, I realise this price is really nothing.

3) How can yoga be used as a healing tool in conflict zones?

Yoga can be a healing tool, to put it extremely simply. For communities affected by conflict, yoga can potentially alleviate PTSD symptoms, transforming our reactions and relationship to fear at the very core. For communities that, unconsciously or consciously, practice oppression, PTSD is not the main focus. Often yoga can be a trigger for unpleasant experiences and anxiety.

If the intention of both study and the teaching is sincere, self knowledge would hopefully lead to eradication of fear, fear of the other. “When the student is ready, the teacher appears,” an old saying goes. I do not believe yoga necessarily offers “reconciliation” in conflict zones as some sweepingly claim. People need to practice authenticity one by one, and see the big picture—and it’s not always a pretty one.

I focus on fear because whether one is traumatized, it’s the one common denominator to deal with in all conflict zones. We can only start with ourselves in time to reach others, one by one.

4) How do you explain the religious aspects of yoga to people who are not familiar with the cultural context it emerged from?

Living in a Muslim country, I do not teach chanting unless I am asked out of sincere interest; I cannot impose it on anyone. I try to deliver it as a breathing practice, a movement breathing system, or a study in mind-body connection.

Most people come to yoga because of back problems, or the multitude of ailments that can result from stress, hearing that yoga might offer a solution. As I mentioned earlier, I avoid teachers who are barking orders without compassion for what the student has come to learn, perhaps because they were taught that way—which is a lazy excuse for confusing their students. I am grateful that none of my teachers were like that, or else I may have decided yoga is not for me.

My teacher, Eddie Stern, often reminds us that gurus are a cultural phenomenon that belong in India, not the West. Any true guru would also define himself as a student, and only seek to empower his or her student. As teachers and students, we need to be more discerning on a moral and ethical level.

5) Have you experienced problems with conservatives in the Middle East who do not like the religious connotations of yoga?

One does not have to be a religious conservative to dislike yoga’s religious connotations. Atheists often reject it even more! Many of my students simply want to learn yoga in order to deal with the stress of Cairo and life in general. Others who are quite religious may feel more of a connection to their spirituality through the practice.

I often get told by Muslim students that their prayer has taken on a deeper quality since starting a personal yoga practice. As I said, initially this is delivered as a breathing movement system. I generally like to avoid problems if I can, so out of respect for being in a Muslim country, I keep all dogmatic ideas out of it. This is the way I was taught, in New York as well as in Cairo. If one is in the practice long enough, they may come to experience that attachment to dogma of any kind will not serve them in the long run.

Here is an excerpt from Krishnamacharya’s (known as “the father of modern yoga”) “Yoga Makaranda.” Krishnamacharya didn’t have the authority to practice yoga, according to the Shastras. He was not only way ahead of his time, but certainly understood the times we are in now:

“Everyone has a right to do yoga. Everyone—brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya, sudra, gn ̃ani, strong, women, men, young, the old and very old, the sick, the weak, boys, girls, etcetera, all are entitled to yogabhyasa with no restrictions on age or caste. This is because yogabhyasa rapidly gives maximum visible benefits to all. It does not stop anybody from acquiring the visible results of practice, whatever their capabilities. Everyone is entitled, irrespective of caste, to follow the path of yogabhyasa.

But many do not agree with this opinion. This only reveals their confusion and the absence of a sattvic state of mind. (The sastras do not forbid yoga for anyone.)”

~

Author: Vikram Zutshi

Image: With a permission of Mira Shihadeh & Urban Sutra

Editor: Sara Kärpänen

Copy Editor: Khara-Jade Warren

Social Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Read 1 comment and reply