The lots were big on the dead-end street where I grew up.

Long green lawns stretched across the landscape draped in clover and dandelions, making constant work for honeybees.

There were no fences to block the view or contain our streetball games, and we played across the yards of friends and neighbors without caring much about boundaries. We knew to use a tennis ball to avoid breaking any windows.

Mr. Bremer’s house sat way back off the road beside a patch of woods that was our playland frontier. We were explorers looking for caves, tree forts, or snakes. We tested our strength by climbing trees or daring each other to jump the drainage creek without sliding back into the mossy slime. It was the perfect cocoon of danger within safety. We could flail about the wilderness feeling like reckless buccaneers, knowing we would be home in time for the normalcy of a hot supper and homework. We knew nothing about the raging world outside the cocoon of Vietnam, riots, lynchings, civil rights, or political scandal.

Our play taught us how to police ourselves under the rules of the social order. We played hard, didn’t tolerate cheating, and tended to each other when we got hurt. We always wanted to do the right thing. We learned that we were not alone; there was a place we belonged.

In 1970, Geno moved into a house down the street, the first African-American family in our neighborhood. The people next door promptly sold their house. My parents explained that some people were prejudiced against black people but that this was wrong. I made it a point to show that I was not like that. I introduced myself to the family, and Geno and I played hot wheels and board games at his house and mine. We welcomed Geno into our gang of boys who played baseball and football in the yards around the neighborhood. He fit right in.

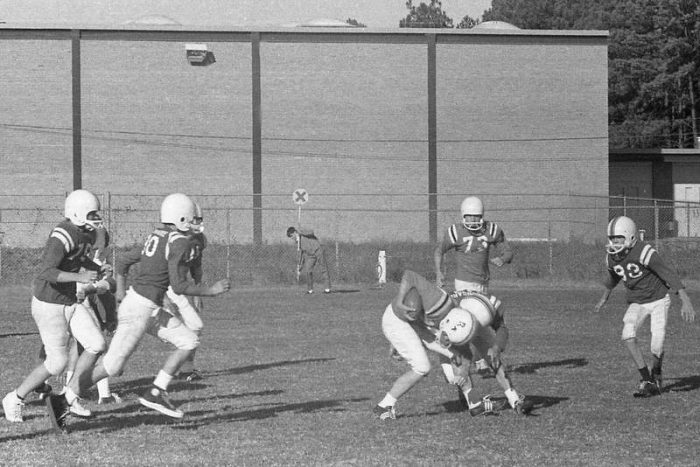

We sometimes played a one-against-all tackling game. We would throw a football high in the air, and whoever got it would run for the goal line while everyone tried to tackle him. We had a rule that you couldn’t tackle someone around the head, like bulldogging in a rodeo. If someone did, we immediately called him out.

I don’t know where it came from, but we used a racial slur to name the infraction. Maybe one of us heard it from his parents; maybe it had been passed down as an inheritance from generations of older boys who had aged through the neighborhood. I didn’t think anything about it at the time; it was just a word we used that meant the tackler had broken the rules. One day, we were playing the tackling game and someone’s arm slipped over the runner’s head.

One of us shouted, “Hey, no nigger tackling!” I don’t remember who said it; it could easily have been me.

And then, right on its heels, someone else shouted, “Guys! Geno’s here.” A shock wave hit us, and the group went silent. I looked over at Geno. He stood by with a blank expression. No one said anything.

We finished the game and everyone went home, unusually quiet. What had been a casual word that we dropped with ease now had a weight we had not seen before. It was no longer pointing at some imaginary rule-breaker. It was pointing at someone we knew and wanted to be friends with.

Geno never played with us again, though I regularly went to his house to ask. I felt the need for repair, to our friendship and to the cracks that had surfaced in our cocoon. I wanted things to return to how they had been before the word had been spoken, but sometimes cracks come at a cost.

We thought the rules were there to protect us, that the social order knew what was good and what was bad. But between the cracks, I could see our moral code had been too small, that we had left some pieces out. As children, we are more vulnerable to the shock that comes when something true is revealed, but we are less able to articulate its effect. So we stand there, with blank expressions, trying to see where it fits.

I would walk over to Geno’s house with a sensation in my stomach, one that I can now name as a mixture of hope and dread, and ask him to come out and play. But he would shake his head in the doorway and say he was busy or didn’t want to. We didn’t know how to talk about it, but we both felt the pain of the cracks. He more than me, I am sure of that.

After a while, I stopped asking him.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

Read 2 comments and reply