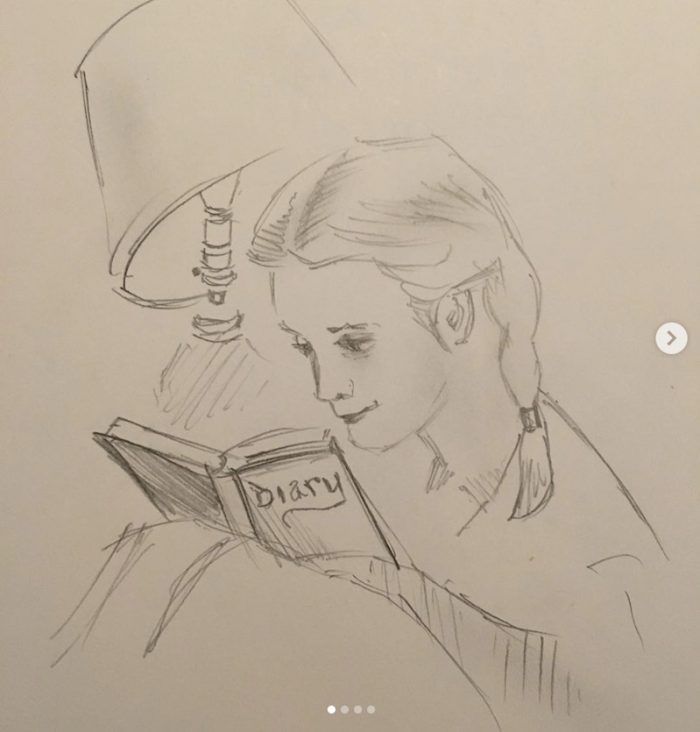

Above: my seven-minute mindful art sketch with Kripalu at the Norman Rockwell Museum of a detail of Norman Rockwell’s “Day in the Life of a Little Girl.” And, if you click here, the work by Rockwell it’s based on.

Waylon at Norman Rockwell Museum & Kripalu.

I’m in Western Mass following a fun 18 hours in NYC.

I’m at Kripalu, a retreat center for yoga, meditation, healthy living. The food is amazing, yummy, healthy, tons of vegan options though they serve meat and dairy too. I’m here for an art/meditation/yoga retreat, as press, and working a bit day-to-day on Elephant Journal.

The reasons I came: to finally check out Kripalu, which I worked with way back in ’99 when I was a kid learning program development and marketing with Jeff Waltcher in the Boulder offices of Shambhala Mountain Center.

And to see Norman Rockwell’s museum collection, and his studio.

I’m in heaven. I also just love taking classes and learning and meeting people who I wouldn’t normally hang out with–old, young, diverse backgrounds and heritage, and from all over. Today we did a 7-minute exercise after touring the Museum and the grounds, with historic buildings and his art studio, where we sketched a detail of a painting that we connected with.

For those who don’t know Norman Rockwell, he’s remembered mostly as that most American of illustrators. But his work goes in the opposite of cliché–into the lives of ordinary people, the details (like good writing) not the artifice in daily life, and touches on themes of liberty, colonialization, segregation, civil rights, nuclear war and peace, and the best of fundamentally good humanity through it all.

He managed to be quite controversial in his time, which we conveniently forget, now—but he was the opposite of nationalism, he was a humanist, a daily cyclist, a modest and funny story-teller who managed to include serious and even solemn or heartbreaking themes into his work while keeping him accessible.

If I could do that, in my work, I’d die (and live) happy.

When I was in high school, in Vermont (a state Norman Rockwell spent years in), I was thoroughly involved in art, and contemplated going to art school. I had a wonderful bold brash and funny art teacher, Mr. Golden, who cultivated us all. I was honored to do a mural on a wall of St. Johnsbury Academy (I struggled with the medium, I’m sure it’s gone now).

But for all my hypothetical talent and passion for art, I didn’t have the guts to go into art as a profession. I didn’t know how to make a living doing so without doing commercial art or art for commission, which at the time I didn’t want to do. And I’d already been broke my whole life, and didn’t want another few decades of that.

Now, I think I could jump into art professionally—with the networking, galleries, openings—and enjoy and succeed at it (whether I have any talent left, dusty as it is with disuse, is another question). But then, I didn’t have the tools, or the confidence.

Elephant Academy—my online training school in Right Livelihood—trains our students in the skills you need to join your love with your work, and make money doing so, and be of benefit doing so. If I’d had it then, I might be an artist, today. That thought makes me want to cry, a little.

Join Elephant Academy.

More: (click for full)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBL6tkXAxPf/

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBrs5bBgxsj/

https://www.instagram.com/p/CB6gYozH3sv/

Could have been this week, or last, not 55 years ago.

Southern Justice, also known as Murder in Mississippi, by Norman Rockwell, in 1965.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 22 comments and reply