Lately, in my liberal and progressive circle, the issue of whether or not government buildings should fly the Confederate flag has turned into a public forum for bashing the South as a whole.

I have absolutely no doubt whatsoever that the Confederate flag has no role to play in our government institutions, and that flying it perpetrates a long and incredibly entrenched tradition of organized racism, bigotry, and terrorism. I believe, without any hesitation in my heart, that this flag must come down as quickly as possible, and that we as a nation will be better for it.

At the same time, I really want our country to pause for a minute, to add some nuance and deeper understanding of what the flag means to some of the people in the South.

Not every single person in the South, who uses the Confederate flag to self-identify as Southern, is racist.

Yes, when they use the flag, they are inevitably (despite their best intentions) behaving in a way that communicates an allegiance to racist ideals. And yes, as a nation, we need this to stop immediately. But we are not using very effective ways to communicate this need.

We are telling them instead of showing them. We are yelling at them. And although this might be necessary at this point (sometimes we must yell when the issue at hand is extremely urgent, as it is in this case), we should also listen and show some amount of understanding that not everyone who flies the Confederate flag is intending to communicate a racist message.

I was raised in Kentucky—on a farm that was smack dab in the middle of rolling knobs. “Knobs” is the word the locals use for the beautiful forested hills that in the fall become a riotous cacophony of color that you have to see to believe. In the spring, the woods are filled with sassafras trees and dogwood. You can eat the leaves of a sassafras tree, or dig up the roots and make a tea from them. Both the leaves and the root have the most distinctive taste — a taste that is unique and strong just like Kentucky itself.

On one side of our farm there was a hollow. A “hollow” is a ravine between two knobs, that creates a tight valley where the foliage allows for mushrooms, snakes and turtles—even snapping turtles. The snapping turtles are huge, ancient-looking creatures. When you stumble across one on a walk, you question your own eyes, because it’s hard to believe that such an amazing animal could be living so near to you—and you had never seen it before!

The sights and smells of the land, the way blackberries grow wild in abundance, the smell of the deep, fertile earth with all of its secrets, the creeks that sometimes overflow after a deep rain fall and then recede to expose perfectly formed arrow heads made by the Native Americans who used to live on this same land—all of these things feel like secrets to me. Secrets that the Southern people share.

There are other secrets too—good secrets. Not shameful secrets like racism and bigotry. Beautiful secrets that small towns carry—how your neighbor is someone whose ancestors once farmed the land beside your grandmother’s grandmother. How—over generations of living in the same town—the people who live side by side with you are something more than neighbors. Not family, but almost.

There should be a word for the relationship that people have when their families have lived beside yours for many generations. The joke of cousins marrying, and the ways in which the rest of the country makes fun of the South for this possibility, is micro-aggression against the South. It’s a way to take a little stab at them, and afterward claim we are just making a light joke, and any offense they take is on them. They’re being too sensitive. Taking offense when we were just joking. If they take offense, we imply that it’s because they are so backward that they don’t even know enough not to take offense at such a minor infraction.

Every time we do this, we are calling them fools and trying to get away with it.

There is a history in this country of micro-aggression against the Southern way of life. And when we try to shame the entire Southern part of our country over the issue of the confederate flag—without acknowledging this ongoing problem of communication—we are working against the bigger and more important issues at hand.

Right now, our whole country is lashing out at the South, and we need to stop if we want to have any hope of accomplishing what we need to accomplish—real movement toward better understanding and inclusiveness for everyone.

We need to give Southern people a chance to tell their experience, without judging them. We are asking a large group of people to make an enormous change, in more ways than one. This is hard on both sides and requires kindness toward each other.

We want the South to recognize that the confederate flag is a symbol of racism and must be removed from public places. But just like the flag is a symbol, the entire discussion is a symbol of a greater conversation, and we need to recognize this truth.

Any discussion of the issue that pretends the only thing we are asking for is that they remove the offensive flag, is avoiding the bigger conversation. And let’s be honest, we’re not asking, we’re telling. Demanding really, if you look at most media on the subject. We humans—when we have insight into right and wrong—cannot seem to help becoming loud, strident, judgmental and preachy. I include myself in this category. It feels almost impossible to avoid.

What we are really telling the South, when we tell them to take down the confederate flag, is that we know better than them, and that they need to learn some things the rest of the country knows already. We are telling them that they should bow to our greater insight.

We are preaching to the South. We are telling them, instead of showing them, what is important. And we are judging them. We are trying to be their body, heart and mind for them, when they have their own unique body, heart and mind.

In the present day, it is almost the rule in our country that we move from place to place and take jobs in different places—put down roots and learn another local variance on all the same things. One of the beautiful things about America is that we have so much variation in our culture.

I have lived in many places in the United States. I grew up in central, rural Kentucky, moved to Brooklyn when I was fourteen and Boulder, Colorado when I was sixteen. From there, I moved to Cincinnati when I was eighteen, State College, Pennsylvania when I was twenty (also Telluride and Boulder in my twenties), then San Francisco for ten years and finally, Denver where I have lived for the past eleven years.

Every place I have lived sang the same tune in a different key. There was always, always a refrain humming along in the background of the local conversations, about municipal rules and regulations that went something like this: People who haven’t lived here for a long time, don’t understand the situation. They are coming in here throwing their weight around, and we don’t appreciate that.

I suspect that no matter where you live in the world, this little ditty is familiar.

It’s because there is not a human being on the planet that likes being told what to do. And this is especially important when the person doing the telling doesn’t have enough knowledge to understand the so-called problem they are trying to solve. The resentment inevitably builds if the outsider trying to give instructions does not have an ear for emotional subtext—if the person giving instructions cannot see, really recognize and respond to the other person’s feelings on the issue at hand.

Feelings in the South are running high, and we as a nation need to listen.

Yes, the flag is a symbol of racism. Yes the flag should come down from public places as quickly as possible. However, we need to understand how this makes people—who have flown this flag with no intention of supporting any aspect of racism, much less slavery—feel. We need to actively listen. If we have any hope of making this change in hearts and minds, and not only bodies, we need to actively listen.

Active listening involves mirroring other people’s feelings.

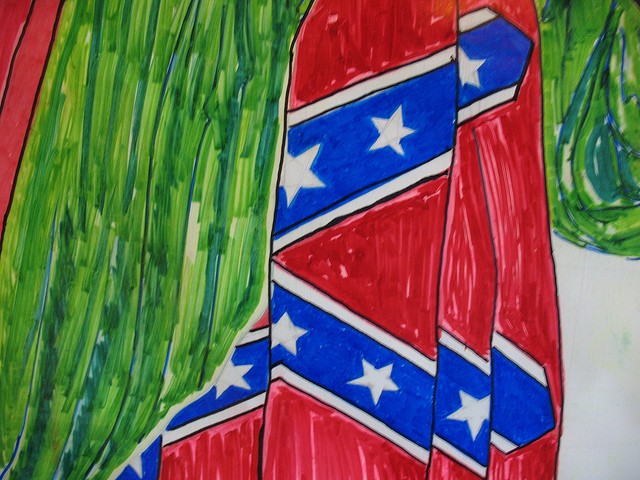

The summer I turned fourteen and moved from Kentucky to Brooklyn, I painted a Confederate flag on the wall of my bedroom. I felt scared in my new home—scared of all the many things that were new and different. In Kentucky, I had only one African American friend. I had never lived with so many different shades of human. I feared my new home in all the stereotypical ways that you can imagine.

I was a small, white female with a strong Kentucky accent, and let me tell you how scared I was—I didn’t walk anywhere outside my apartment without putting my keys between my fingers, so that if someone attacked me, I could try to take their eyeball out.

I tried to appear aggressive and in control, because I thought that at any minute, someone might try to hurt me. I was afraid of people giving me drugs, tricking me out of my hard-earned allowance, misleading me on the bus to places where they might rape me, making fun of me and laughing at my small town ways.

It took time and patience for me to learn to fit in, at least a little. I knew everything was going to be okay when I earned a tiny bit of fame in my high-school halls for being the girl with the accent. It was funny to me, that in this town where so many different nationalities seemed to be present—there were people from Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nigeria, Puerto Rico, Italy, Russia, Poland and so many more—the girl from Kentucky as the foreigner.

In between classes, as we all filed out of one room and made our way through the halls to another, it was more the rule than the exception that someone I didn’t recognize would yell, in a friendly manner, “Hey Kentucky!” (That had quickly become my nickname.) “Say orange!”

I would smile and yell my version of the word “orange,” then I’d receive a round of good-natured joking, and I knew that it was okay to be different. I was an oddity, but no one thought this was something to attack. My Brooklyn classmates found this interesting, not scary.

When you live in the South, and your family has lived in the South for so many generations, things that are different tend to be scary. This is not unique to the South. It is just human nature. But it is pronounced in the Southern parts of our country, because of the fact that there is a tradition of staying put.

It is common in our country to move around, to travel and to talk about the value of doing so. What we don’t often do, is recognize the value of putting down roots. Communities that have many generations of families that have lived together, have a deep and abiding nature, that we don’t often recognize as necessary and valuable.

If you’ve never lived in a rural place or a small town, you might not realize what this does to a soul. You might not know that there is value in this, and you might say something like, “Those people in that small town—they don’t know what they’re talking about because they haven’t traveled. They haven’t seen the world and exposed themselves to all this other stuff. So we need to expose them. We need to tell them what’s what.”

The more interesting thing would be to listen.

When I painted the Confederate flag on my bedroom wall in Brooklyn, I was not referencing slavery. Okay, I might have accidentally been doing so—and I see that now. But at the time, I was telling the world this one thing and this one thing only:

“I am from the South and you should fear me. I am strong and independent and I don’t take orders. You don’t understand because you haven’t lived there. You only know the stereotypes of the South and the real South is something different—it’s an in-secret that you don’t have access to unless you spend a little time there.”

I agree that the Confederate flag is a painful reminder of our nation’s brutal history and the genocide we committed. I agree that we should stop using the flag as a symbol of Southern pride.

As a country, our hearts and minds are expanding to make room for other ways of doing things—for inclusiveness and acceptance. For understanding and healing. If the United States had a body, it would be turning right now and walking slowly—too slowly for many of us—toward a place that is so much better than where we’ve been.

We all know we need to make room at the table for people who are different from us. We are only as strong as our weakest and most vulnerable people. We need to see less economic divisions, less racial divisions and less gender divisions. Mostly, we need to stop stereotyping each other, and start working together. I think our entire country agrees with this sentiment. And the people who don’t—the people who would commit crimes and fill their hearts with hate because they are threatened by the need to work together—we can and should isolate them, and protect ourselves from them. Hate should not be condoned in any form. And the people that would lead with hate and act with hate, have no place among us.

There are many marginalized people who deserve a place at our table. We must invite everyone to participate. There is a population that I think we are forgetting—people who also need to be included in this slow move toward a better life for us all. That population is the South.

The little girl who displayed a Confederate flag on her bedroom wall—because she wanted the world to believe she was strong and independent, not because she was racist—also has a place at the table. Listening and understanding her perspective—showing her how the flag she painted miscommunicates and actually works against her message—this is the most effective way of getting her to the table. Not yelling at her and shaming her for doing something that we don’t understand.

When we have conversations with people we care about, we know that active listening, true understanding and real empathy help us in our efforts to communicate. Sometimes, this is more painful than other times. In the instance of the Confederate flag, the pain reverberates through our nation, because of the way the roots are planted so deeply, and because of the continuing hateful aggression and crimes (big and small) against minorities that happen on a daily basis.

This is so important and urgent that we must all work hard to change it. At the same time, we must recognize that most of the people in the South who are emotionally attached to the Confederate flag, love this flag for the ways in which it is a symbol of how they once stood up to a government body that they perceived as a bully.

Whether or not the North was a bully to the South during the Civil War is up for debate. Whether or not the South perceived the North as a bully, is not. The fact is, the South felt stepped on and misunderstood. We are re-activating those feelings in them again when we do not take the time to understand this one simple fact.

We can, and should, judge our ancestors for their crimes. But we also can, and should, listen to and understand our friends, neighbors and families. Those who have not committed any crimes and have no hate in their bodies, but who still feel attached to the flag.

Because the most powerful change happens when we do not force someone to do something different, but we change their hearts and minds, and then they make this change of their own free will.

Hanging the Confederate flag is not, in and of itself, a crime. It is an offensive assumption to judge a body of people who hang it, as racist. If we do not see that, we are not understanding, and we need to seek understanding, in the same ways we are demanding that of others.

.

Relephant Reads:

Why we shouldn’t be so fast to ban the Confederate Flag.

About that Symbol of the South.

.

Author: Emilie Mitcham

Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Photo: Flickr/Cuauhtemoc-Hidalgo Villa-Zapata; Flickr/eyeliam

Read 4 comments and reply