Funerals are necessary things. They allow the mourners to ritually memorialize the deceased and to provide a container for shared loss and grief.

But to what extent is that grief allowed to express itself in such settings, if at all?

When my father died we were going to have his memorial service at the nursing home where he’d spent 12 hours a day every day for 10 years sitting at my mother’s side while she died of Alzheimer’s, but we decided against it.

While my father had assumed heroic proportions at the nursing home for his constant vigilance and attention to my mother, the people there didn’t know he owed her that much. They didn’t know he owed her for all the broken promises, for all the other women, for all the flying plates and slamming doors and for the sheer hell of being married to a Purple Heart/Navy Cross U.S. sailor that suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder before it became so well known that they had to give it an acronym.

Besides, by the time my mother was in the nursing home, my father had nothing else to do with his days. He was getting old and wasn’t too strong himself and in the end, he felt guilty and, if guilt can change a person, it certainly changed him into the simply sweet old man he had become by the time of his own death.

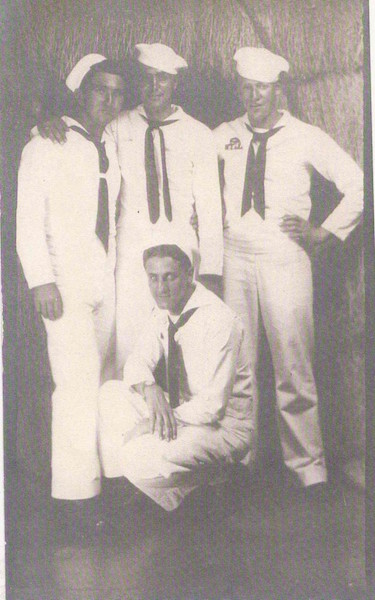

At the end there was $2,000 left in his checking account. His entire estate. My brother and sisters and I used it to pay for the burial of the ashes and the memorial service where a priest from the Veterans’ Hospital said Mass behind the dining room table in my living room and a black and white photograph of an eager young sailor in white bell bottom trousers, stood silently nearby.

My sister sang Ave Maria and my nephew played the guitar as our intimate family group reminisced about the man who connected us to each other. It was a simple and touching tribute to an extremely complex person and when the ritual ended, my brother stood up and announced, “Let’s eat!” rubbing the flats of his palms up and down together the way our dad always did.

So, we ate and we drank and we laughed and we played Sinatra and Bocelli and Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World, the song my father had requested we play at his funeral. I was sitting on the patio with my six-year-old granddaughter on my lap when it hit me. My larger-than-life father, the flawed and highly charismatic man who stood in the spotlight of my life wasn’t there to eat salami with us or drink martinis with us or to make jokes with us and he never would be with us again and I cried as quietly as I could; I cried.

“It’s all right, nana, it’s all right,” my granddaughter had said, her little girl arms coming round me. In the background I could hear Louis Armstrong proclaiming that this was a wonderful world and a rush of feeling swept over me. The last thing I wanted was to hear Louis Armstrong singing about how it was a wonderful world. How could it be a wonderful world with the first man in my life gone from it forever? The man who took with him the memory of riding on his shoulders when I was three or of him teaching me how to cook “real” Italian food or of hearing him sing opera in the shower every morning? How could it be a wonderful world when the man who was all the wonderful things he was—as well as all the not-so-wonderful things he was—had taken a huge piece of me with him when he died?

I didn’t want my father to be gone and I was angry at him and lonely for him and filled with grief for him all at the same time and, no, I didn’t want to sit and cry quietly.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to roar, “No!”

But that wasn’t the place or the time for such expression.

In fact, I would swallow my “no” for over a decade until, one day, entirely unexpected, I would see on my Facebook feed a group of students halfway round the world mourning the loss of their beloved teacher/father figure. When I stopped and watched, it occurred to me that they were behaving exactly as I had felt like behaving all those years ago at my father’s Sinatra/Bocceli/Louis Armstrong memorial service.

Hot tears began pouring from my eyes as the mourners bravely, unashamedly called out their feelings, their grief and their loss. So moving, so powerful was their call that it swept me up in it and I felt myself calling out with them in my heart.

A wave of gratitude washed over me for those mourning, wounded students; gratitude for their animal sounds, for their raging and for their wailing.

Were it possible, that is exactly what I would have done at my own father’s memorial but for a myriad of reasons—culture, tradition, personal reticence—it simply was not possible. Through the students’ fully expressed paroxysm of grief however, I finally felt I had fully expressed my own.

“No!”

And with my cry came a relief such as I had not known.

I replayed the students Maori Haka several times, letting my tears flow while raw emotions washed over me.

Just before I watched it for the final time, I felt myself saying inside, “Yes. Yes, dad, ‘It’s a wonderful world.’”

~

Relephant:

The Only Nice Thing My Mother Said to Me When I was Growing Up.

~

Author: Carmelene Siani

Editor: Travis May

Image: Author’s Own

Read 0 comments and reply