Growing up in the 60s and early 70s, my Irish mother had a favorite idiom with a practical application. It was, “waste not, want not.”

Although not yet the era of recycling in Ireland, it had the same mentality: don’t toss what can be reused, albeit in a different, less appealing form. Like turkey broth soup complete with gizzards.

Point being: if it’s reusable, not poisonous, and still edible, it would be an egregious act to discard it and go shopping for fresh food we can’t really afford. Thus producing unnecessary expense and waste.

Thomas Rau, an innovative German architect, has dedicated his life to reinventing the way we design, produce, and market our materials, so that they are put at the service of the consumer on a rental basis—not on an ownership basis whereby we discard everything from light bulbs to refrigerators once they have died their predetermined death. Thus accumulating more waste and expenditure that serves no-one but the fat-cat entrepreneurs who have rigged their products to live a limited lifespan. Why? Obscene profits of course.

His ideas are collected in the Turntoo concept, which is a fundamental shift in the way that products, buildings and other designs are considered. In essence, the idea purports that any artifact—from a bicycle to a skyscraper—is a resource bank for raw materials.

From this, it follows that the item’s original material is still usable at the end of the product’s life cycle. So why dispose of it? A building may be taken down after 30 years, but the steel within is still perfectly usable. Here Rau goes one step further in proposing that we design our buildings, cars, and so on, in such a way that they can be disassembled as easily as they were assembled.

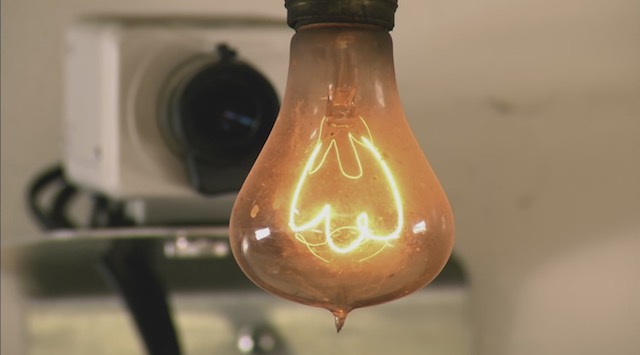

In his view what the consumer really wants is a service, rather than an object. You want adequate lighting in your home, you don’t need light-bulbs ad infinitum.

Yes, but businesses don’t want you to buy a single light bulb that can burn longer than you’re alive; they want you to buy many bulbs over the course of your life. Therefore, if sustainable products are going to make it, this requires a new economic model. The End of Ownership documentary tracks Rau’s progress as he presents this new model to the business community.

Shortly after Thomas Edison invented the light bulb, a committee assembled to determine the economic viability of such a product. They agreed to maximize their profitability by designing an inferior bulb that would bow out at 1,000 hours. Such fabricated limitations on the bulb, ensured that many more bulbs could be sold. In Rau’s view, their decision spawned an environment fraught with waste that placed an unnecessary responsibility on the consumer.

(For fun, why don’t you check out the world’s longest burning light bulb, hanging from the ceiling of a Livermore fire station in California for—wait for it —114 years! And still going strong.)

As noted in the documentary:

“Rau approached the Phillips technology company with a proposal: produce lighting solutions that work for the consumer, and assume the power costs as their own. In theory, the benefits of such an approach would be desirable for the consumer, the business, and the environment. The consumer essentially pays a rental fee for their lighting. Since the company is footing the electric bill, the product they provide is carefully designed to operate with extreme ease and efficiency to keep costs low. Currently, the program is rolling out across the business sector, and is resulting in astronomical energy savings for all involved.”

Rau’s revolutionary new economic energy model has much potential beyond the light bulb. The public housing sector is now creating more efficient appliances throughout their properties as a means of saving money for their tenants. Meaning low income tenants can now rent high quality appliances for a modest monthly rent. And if it goes on the blink, the manufacturers who have provided the service, will gladly repair it.

And when it eventually needs to be replaced, this “bank of raw materials” will not end up in the landfill. But will be redistributed in the manufacture of another quality appliance, with minimal or zero waste.

Now selling stewardship, service, and moral responsibility may not be the next in vogue trend in the marketplace of aggressive commerce. But, from where I stand, its innovative entrepreneurship and raw passion for the common good of Earth and humanity, will not be going away any time soon.

~

Author: Gerard Murphy

Images: Video Still

Editor: Travis May

Read 0 comments and reply