Waiting for my father’s flight to land, I was nervous and apprehensive.

It had been over 10 years since we’d seen each other. I worried whether there’d still be tension between us or whether we’d recover that precious father-daughter bond which had always united us in the past.

It had been as many years since my parents finally separated after 40 years of marriage. This violent tearing of the fabric of our family produced wounds that are still felt by each of us—my father, my mother, my sister, and me. The emotional fallout led to a breakdown in communication with our father.

Watching our families disintegrate is a raw and painful experience no matter what age we are.

My sister and I were both married with children by then, and it had also been clear for decades that there were problems in our parents’ marriage. All those facts did not lessen the pain.

In the process of separation, our mother had somehow slipped into the victim role and my sister and I had somehow slipped over to her side.

I remember my last conversation with my father before the silence…

He was trying to explain something to me, but I could not bear it and cut him off, sticking to the official line that my mother was the suffering party and that he was a coward. We often call men cowards when they are unable to express their emotions openly and instead hide, lie, and cheat. But everyone has their own point of view and everyone deserves to be heard.

I did not know then—still attached to a singular version of the world as I was—that many years would pass until we would speak again. Now that we are talking, we try to make sense of all the lost years and of what happened to my parents and us as a family.

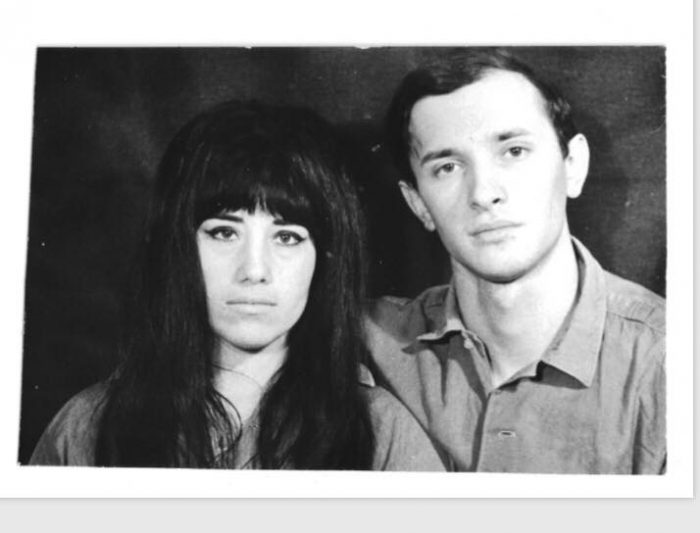

What I realize now is that my father is not your “typical” coward. He’s even been called a hero. He had the courage, passion, and strength to question and stand up to the authorities in a totalitarian state and fight for his human rights and freedom of speech. He finally broke out of the Soviet Union, after years of being persecuted and imprisoned, and pivoted the destiny of his children, driven by the desire to give us a “better” life.

Yet that same man could not summon the same courage to face his own emotions. To stand up to my mother. To disentangle from the guilt and pressure to keep it all together for us, his beloved daughters. The thought of facing the woman he chose and married, with whom he raised and educated children, and shared many decades of life, and telling her that he was unhappy was unbearable.

He was not afraid of risking his life to stand up to an authoritarian regime, but he was completely helpless in the face of his own emotions, and expressing them to his partner. He felt guilt and self-hate for being unhappy despite my mother’s best efforts and sacrifice.

As I observe both of my parents now, I cannot help but admit that they are both so much better apart. Having left the familiar setup of their marriage, they have both had to rebuild their lives practically from scratch in their 60s. It has been hugely disruptive for them and all of us. Habits, no matter how detrimental, are comforting. We all prefer the familiar to the unknown.

My parents’ biggest mistake was holding on too long to the illusion of what a family is and ignoring their own emotional signals.

Both of them were completely unaware of the concept of self-love, having been raised in a state where individual human life held no value. Had they been more attentive to their feelings and allowed themselves to express them, perhaps they would have been able to act sooner—either to improve their relationship with each other or to make the difficult decisions to separate and give a new life a chance.

Perhaps, they would have been able to communicate and find a balance through acceptable sources of joy outside of their marriage, whether from creative pursuit or other relationships. Instead, they both kept quiet, each in their misery, silently blaming each other for not living up to the dreams and potential of the projections of their youth. My parents kept their marriage together out of the ingrained belief that they are not worthy of personal happiness, using children as the excuse to not disrupt the status quo.

Such a life is unsustainable—it poisons and destroys everyone who participates in it.

Having had the distance of several years to observe this story, I would like to tell all the parents who override their need for personal happiness for the sake of their children: we, the children of unhappy parents, can spot the lies, the tension, the misery. Even if there are no dramatic fights, we notice silent tears, we pick up on the sadness, the despair.

Moreover, the way parents choose to deal with their unhappiness sends powerful messages to their children about how to deal with problems when they inevitably arise in their own relationships. Lies and words left unspoken leave scars and wounds just as deep as the wounds of a breakup. It is not by keeping the lid on pain, nor through silence and fear of emotional outbursts that we will keep our children out of harm’s way.

A lack of self-respect and boundaries and making too many sacrifices sends the wrong messages to our children about what we should be willing to accept in a relationship.

Having been married for over 25 years myself, I by no means preach to run at the first sign of dissatisfaction. It is important to disentangle whether we are unhappy out of disappointment which arises out of our own unrealistic expectations, or because our relationship truly blocks us from being ourselves.

One of the most striking realizations is what miserable people both of my parents had become within their marriage—each stamped with profound loneliness and lack of connection. Many years of unhappiness made them close in on themselves and even withdraw from us, their children. They became so low on vital energy that they turned into mere shadows of themselves.

As soon as they freed themselves from their dysfunctional union, they were each able to reach their potential. Amazingly, nothing was an obstacle—not their age, nor their circumstances. As soon as they stopped bending themselves to the prison of conditioned expectations, they each relatively quickly rediscovered their former selves and have both grown into people whom I am proud to call my parents.

My mother—who I always remembered as a crying mess of loneliness and depression—has, in the span of five years, become a cheerful and happy person with lots of friends and a vibrant and active life, which she never had when she was much younger and married.

My father—who also seemed beaten, incapable of taking care of himself, and withdrawn in my last memories of him—is a wise, calm, and self-sufficient man today, who relishes being alive and free.

We are so programmed in our expectations and ideas of marriage and how it is supposed to unfold. A tool of patriarchy designed to keep everyone in assigned roles, it’s become a prison of sorts. The expectation of a spouse as deliverer of solutions for most of our needs and desires leads to inevitable disappointments. There is no single formula for what makes us happy in partnership, each of us is unique, and messy, and human, each with our own stories and familial dysfunction.

Having three children of my own, I am well aware of what is at stake when a marriage falters. We all want what’s best for our children. But as a daughter of two sadly married people I say that children need and deserve happy, thriving, and well-adjusted parents more than they need married ones. The way our parents treat themselves and each other sets us up for life, affecting our own future happiness.

As I stood at the airport, with my heart pounding, looking at every older man coming out into the arrivals area, watching reunited couples, parents, children, and friends hug and kiss and happily exclaim greetings and pleasure at seeing one another, I wondered, “Will I recognize him? Will I cry?”

There are faces you will never not recognize. There are bonds that cannot be severed.

A hug. A kiss. And the world is restored.

Divorce is the best thing that happened to my parents.

No child ever wants to see their parents separated; it is painful no matter what your age. Issues of loyalty and abandonment trigger wounds that require open communication and compassion in order to heal. But to see the people we love happy is worth it.

I only now realize that had my parents stayed together, I may have never known them in that state.

Read 43 comments and reply