Jack Laws had one enduring memory from his meeting in Denver that day with the wildcatter who bought 35,000 acres of farmland nearly two decades ago, and it had nothing to do with 9.11. When he sat down in the fancy conference room on the 24th floor of the Anaconda Towers, there were four framed black and white photographs, 3-foot x 3-foot, of water gushing from pipes on a farm. Jack laughed to himself. Marcie had been right — he’d been looking for water “from the get-go.” Marcie was always right.

Meanwhile, Marcie was finishing up two days of meeting with El Paso officials and had shaken hands over a deal to sell the rights for $10 million worth of water, the beginning of an endgame for the Laws that could net them 10 times that much money in a decade. But there was a catch, a potentially fatal flaw in their strategy that could blow up the whole deal, and, uncharacteristically, a misjudgment of trust.

At the root of their problem was Winfield Edelman, an Austin attorney who had a history of working with water utilities and a reputation for doing whatever it took to shape the Texas Legislature in favor of a client, even if that meant bending the rules or buttering up a congressman with Cuban cigars and the occasional high-priced escort. At $500 an hour, Edelman had helped the Laws come up with the underlying strategy for their water play, beginning with the Denver group buying their land and the Laws easing out of farming altogether over two decades. Under that plan, the Laws would retain rights to as much water as they could pump from the Bone Springs-Victorio Peak Aquifer and shed the endless headaches of farming in the high desert of West Texas. Edelman knew the science and politics of water in Texas, having worked for several utilities in his early years before earning a law degree at a local night school. Right of capture, which entitled landowners to as much water as they could pump, was the law of the land in Texas, and based on that Edelman assured the Laws that they were sitting on a goldmine.

“Slamdunk,” Edelman told Marcie over pork-cheek quesadillas and dirty martinis in the bar at the Driskill Hotel in Austin, and extended his hand for a ceremonial fist-bump.

Marcie was no stranger to those silly male bonding rituals, but she felt put-off by Edelman’s oily confidence. “What?”

“It’s a basketball thing.

“Oh. What if the law changes.”

“Trust me; it won’t.”

Nobody knew Edelman was playing all ends against the middle, working with two other large Texas farming concerns and a group of small-hold farmers pushing for a change in the rules that could bring down the Laws’ house of cards. They knew full-well what the land barons had up their sleeves, and were concerned that thirsty major Texas cities would pump the aquifers dry, leaving them with land where nothing but cactus and mesquite could grow. The concerns of the small-hold farmers, representing thousands of votes across the state, were no secret, and fists flew on more than one occasion at heated city council meetings. They were pushing wherever they could to amend the law in a way that limited water rights to an average of what was used during a 10-year period, which would cut the legs from under big landowners like the Laws who had all but stopped farming with an eye toward selling water instead. And the gerrymandering of water districts, particularly in West Texas, had made it even more complicated.

Everyone lawyered-up when the law was changed in 2003, in a cluster of cases that would eventually be decided by the Texas Supreme Court.

All Edelman wanted was a plate of Tex-Mex and a few Coronas at Rosa’s Cantina, the iconic hole-in-the-wall immortalized in Marty Robbins 1959 country classic, El Paso. After the law was changed, Edelman had received some threats — phone calls, slashed tires and the like – but he figured it would be safe for one last meal at the nondescript cantina on Doniphan Ave. east of downtown El Paso before heading to Austin. Being Tuesday, the Don Haskins Special was the featured dish, and Edelman had a craving for the lump of Mexican-style meat loaf, mashed potatoes, corn and Spanish rice. He sat in a corner under a racy 1950s-era poster of a busty pinup gal in a bathing suit and sombrero sitting seductively on a wooden fence thumbing a ride down some deserted West Texas highway.

Edelman was feeling pretty good about his grifting after the meal and two shots of Don Julio, and sung a few lines from that old Marty Robbins song while walking with a cocky swag to his black Cadillac El Dorado. “Out in the West Texas town of El Paso I fell in love with a Mexican girl.” Edelman unlocked the Caddy. “Nighttime would find me in Rosa’s Cantina, music would play and, …” he stopped singing as a vile smell poured from the open car door. A disemboweled skunk lay across the dashboard, with a note hanging from the blade of a knife stuck in its chest. “Just keep driving.” Edelman felt Rosa’s meat loaf and mashed potatoes surge through his bowels as he fumbled with the keys, and some of that cream gravy seeped into his boxers with the crack of a rifle and a dull thud into the side of his car. He was out of the parking lot in no time, but not before another bullet hit a few inches from the first.

Edelman never told anyone about it. But he dug out the slugs and took them to a gun expert in Austin, who told him they were from a 30.30. That was his last visit to El Paso.

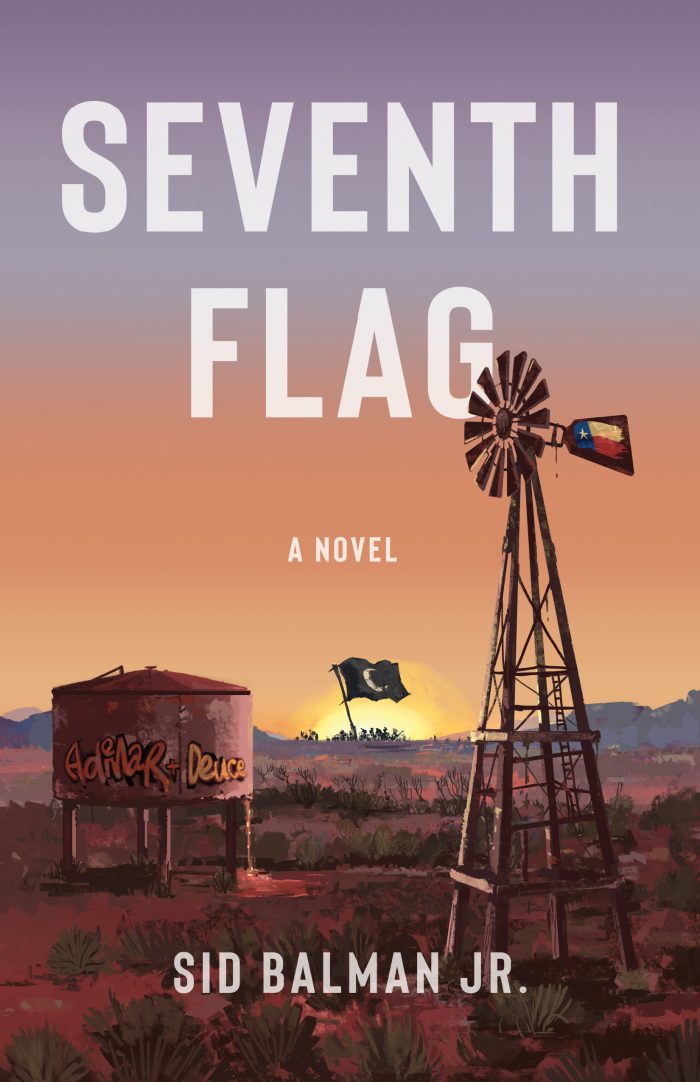

The above is an excerpt from Sid Balman Jr.’s debut novel. A Pulitzer-nominated national security correspondent, Balman has covered wars in the Persian Gulf, Somalia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo, and has traveled extensively with two American presidents and four secretaries of state on overseas diplomatic missions. With the emergence of the web and the commoditizing of content, Balman moved into the business side of communications. In that role, over two decades, he helped found a news syndicate focused on the interests of women and girls, served as communications chief for the largest consortium of U.S. international development organizations, led two successful progressive campaigning companies, and launched a new division at a large international development firm centered on violent radicalism and other security issues on behalf of governments and nonprofits. A fourth-generation Texan, as well as a climber, surfer, paddler, and benefactor to Smith College, Balman lives in Washington DC with his wife, three kids, and two dogs.

Read 0 comments and reply