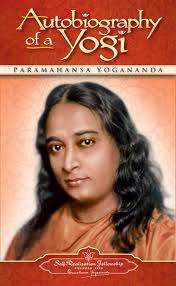

Of all the books written in the 20th century, few if any have launched, inspired, or augmented more spiritual paths than Autobiography of a Yogi. And Paramahansa Yogananda’s iconic memoir is still going strong on its 75th anniversary, more than a century after the author set sail from India at age 27 to offer America the precepts and practices of classical yoga.

The AY, as many devotees call it, is not just an enthralling depiction of a singular life. In fact, readers are often surprised to find that biographical elements occupy fewer pages than they expected. Indeed, so much of Yogananda’s personal story is left out that I was moved to fill in the gaps with a book of my own, The Life of Yogananda: The Story of the Yogi Who Became the First Modern Guru (Hay House, 2018).

Yet the non-biographical content helps explain why the book is so beloved around the world. It offers an intimate view of Indian life at an earlier time. It paints vivid portraits of gurus, saints, and exceptional human beings like Mahatma Gandhi and the revered author and educator Rabindranath Tagore. It demystifies Indian philosophy for the secular, the scientific, and the spiritual alike. It lures readers out of their comfort zones and, in many cases, transforms their view of the world.

And, oh yes, it offers vivid details of miracles and wonders.

When I was working on my Yogananda biography, I had a graduate student quantify the miraculous occurrences in the AY. She counted 132, covering 44 percent of the book. Consider some of the chapter titles: “The Levitating Saint,” “My Guru Appears Simultaneously in Calcutta and Serampore,” “Rama is Raised from the Dead,” “Materializing a Palace in the Himalayas,” “The Resurrection of Sri Yukteswar,” and an attempt to explain such wonders in rational, scientific terms, “The Law of Miracles.”

Why did Yogananda devote so much space to material he must have known would be greeted with skepticism? Perhaps he told us why by including this biblical passage on the title page: “Except ye see signs and wonders, ye will not believe” (John 4:48 KJV).

And capture attention he did. In my experience, the book has two kinds of fans: those for whom the extraordinary feats and supernormal powers are the main attraction and those who dismiss the astounding tales as fiction but love the book anyway.

The seminal text was the crowning achievement of an intense writing period. Yogananda had spent the better part of the 1920s and 1930s crisscrossing America by rail, delivering countless lectures, teaching yogic techniques to thousands of students, establishing a monastic order, and building the organization he founded, Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF), into a viable institution with centers in most major cities. Then he decided it was time to stay put and focus on his written legacy.

A former resort hotel on a Los Angeles hilltop had become his home and international headquarters, and SRF had acquired additional properties in the city, in the desert east of L.A., and in the seaside town of Encinitas north of San Diego. In the more serene settings, Yogananda kept stenographers, typists, and editors busy day and night, working with his prodigious outpouring of handwritten and spoken words.

Of the many projects he worked on, the one he felt would assure the long-term success of his mission was the autobiography. He worked through numerous drafts, helped by his disciple and principal editor Laurie Pratt. The road to publication was not smooth. Rejection letters prompted a series of rewrites, with the author in California exchanging drafts by mail with Pratt, who had been dispatched to New York to oversee publication. Exactly what the publishers’ objections were is unclear, but certainly the esoteric subject matter was a factor, as was the timing: The world was at war and America was mobilized. When the war ended, a prescient publisher finally stepped up to the plate.

The contract with Philosophical Library, a relatively new firm that would go on to publish 22 Nobel Prize winners, was signed on August 12, 1946. It called for an initial printing of 7,000 hardcovers. There was no advance. The publication date was December 1, 1946, and the price of the book was $3.50. Those who know the book’s classic orange cover—with the author’s deep, dark eyes seeming to gaze intently at the viewer—will be surprised to learn that the initial cover was blue.

Reviews were more favorable than one might have predicted for that era, more than two decades before a parade of gurus came to America and practices like meditation became mainstream. With few exceptions, publications large and small found reason to praise it. Newsweek magazine was surprisingly insightful: “Writing for a Western world that seldom understands and often scoffs at the yogi search for union with the Cosmic Spirit, Yogananda, an authentic Hindu yogi, has tried to explain by telling the story of his life. Autobiography of a Yogi is more than an apology for yoga and its techniques of meditation; it is a fascinating and clearly annotated study of a religious way of life, ingenuously described in the lush style of the Orient.”

Some have disparaged that lush style as old-fashioned, but to most readers it’s part of the charm. And it didn’t prevent the memoir from earning the praise of prominent figures such as the scholar W. Y. Evans-Wentz, who wrote the book’s preface, and the German novelist and Nobel laureate Thomas Mann.

The book was not exactly a best seller, but it sold at a steady clip, dramatically raising awareness of Yogananda and his work around the world. When AY was published, SRF had 13 centers in the U.S., a few in India, and one each in London, Mexico, and the Gold Coast (now Ghana). Five years later there were 24 in America, six in Mexico, and multiple facilities in Africa, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere. The book, Yogananda observed, accomplished “what I meagerly did while traveling and lecturing to thousands.”

Yogananda revised his magnum opus in 1951, the year before he died. Mistakes were corrected, material was added based on queries from readers, a new final chapter (“The Years 1940–1951”) was written, and because India had achieved independence in 1947, Yogananda offered, like a bouquet, a proud tribute to his homeland in a lengthy footnote.

He lived five years and three months after his seminal text was published. During that time he worked as hard as he always had, which was very hard indeed, making sure what he’d built would endure after he was gone. To that end, he continued his robust literary output, groomed disciples to carry on the work, and secured SRF’s financial future. The AY contributed to those goals in at least two ways: Book sales brought in revenue, especially after SRF acquired the rights in 1953; and it drew a flood of new students to Yogananda’s teachings, some of whom went on to become instrumental in cementing his legacy.

Over the decades, SRF has periodically updated the book and embellished it with new photographs, captions, and footnotes. To commemorate the 75th anniversary, the organization has produced a deluxe edition with elegant features and more than 100 photographs. (Crystal Clarity Publishers, an offshoot of Ananda Sangha Worldwide, publishes the original 1946 text.)

The book that Yogananda said “will be my messenger when I am gone” has been exactly that. Like all perennial books, it has been discovered anew in each generation, with periodic surges of publicity, such as when Beatle George Harrison revealed that he kept stacks on hand to give away (“if I hadn’t read that,” he once said, “I probably wouldn’t have a life”), and when Apple founder Steve Jobs decreed that copies would be handed out at his memorial service in 2011. Precise sales figures are unavailable, but the book is estimated to have sold at least 4 million copies in English, and it’s been translated into more than 50 languages.

Factor in all the copies that were borrowed from friends or libraries over the decades, and the number of readers at least doubles. In the 1960s and 1970s, the autobiography might have been the most passed around of all the books that turned counterculture seekers toward the East. I still have the copy I borrowed in 1970, and I joke that I write about Yogananda in order to work off the karma of never giving it back. (Hey, it cost five bucks then, and I didn’t have that kind of dough.) I had already stepped onto my spiritual path, and while I never became a formal student of Yogananda, his book solidified my commitment and has enhanced my perspective ever since.

Now, of course, the AY can be found everywhere—small-town libraries, health food stores, and yoga studios alike. There are many reasons why Yogananda has been called the 20th century’s first superstar guru, the father of yoga in America, and the most influential Indian teacher to come to the West. Among those reasons are his gift for integrating East and West, ancient and modern, spirituality and science; a personality that inspired devotion and loyalty; his reluctant but highly competent administrative skills; and his tireless dedication to his mission. But perhaps the biggest factor of all is that epochal text.

During the takeoff of a flight not long ago, the stranger in the seat next to me clutched a well-worn book with trembling hands. When we reached cruising altitude, she relaxed, and I could see she’d been reading Autobiography of a Yogi. She suffered from fear of flying, she told me, and the book always calmed her down.

Read 1 comment and reply