Elephant Journal Logos:

Email us for hi-res logos.

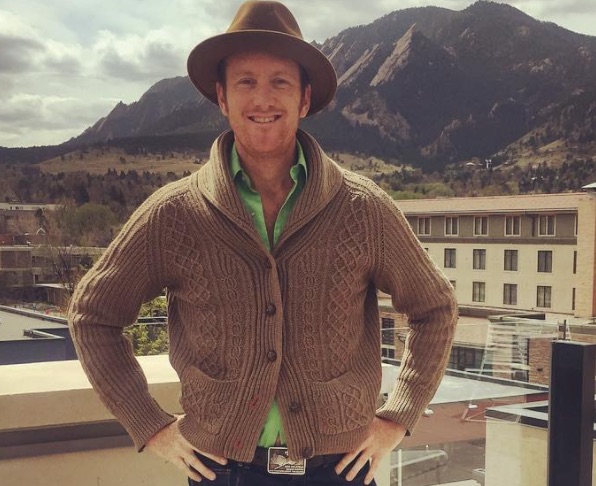

Waylon Lewis photos & bio:

Waylon Lewis, founder of Elephant Journal, the world’s largest mindfulness community, is the host of Walk the Talk Show, an award-winning video series & podcast. A first-generation Buddhist or “Dharma Brat,’ he’s the author of the best-selling “Things I would like to do with You,” and now “It’s Never too Late to Fall in Love with your Life.” He aspires to help change our world for the kinder, and have some fun along the way.

Or

Waylon Lewis is a “Dharma Brat,” or second generation American Buddhist. Founder of Elephant Journal and host of the Top-10 US Video Series “Walk the Talk Show,” he’s been named Treehugger’s Eco Ambassador & Changemaker, Discovery Network’s “Green Hero,” “Prominent Buddhist” by Shambhala Sun, Greatist’s 100 Influential People in Health & Fitness, & 5280’s Top Denver Single. A mediocre climber, lazy yogi & 365-day bicycle commuter, Waylon recently authored “Things I would like to do with You,” a book about a new kind of independent-minded, genuine love affair.

Find Waylon’s full bio page here for more photos, a fuller, more complete biography, and his awards and accomplishments, and his speaking fees.

Recommended:

Older photos:

Voted #1 nationally for #green, twice, elephant has four popular accounts on twitter.

Contents

- Recent Press

- Photos

- Dharma Brats

- Early Days at elephant

- In the Press

- Reviews

- elevision

- Daily Camera Write-Ups

Waylon Lewis Bio:

Full Bio:

Waylon Lewis, a second generation American Buddhist, is the founder of elephant magazine, now elephantjournal.com. A 365-day bicycle commuter, mediocre climber, lazy yogi & featured columnist for Huffington Post, Waylon graduated from Boston University’s top ranked magazine journalism school, worked with Shambhala Publications and Shambhala Mountain Center, and attended Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. Named Treehugger’s Changemaker & Eco Ambassador, Discovery Channel’s Planet Green “Green Hero,” Shambhala Sun’s “Prominent Buddhist,” Naturally Boulder’s “Entrepreneur of the Year” & 5280’s Denver Most Eligible Bachelor, Waylon hopes to serve as the Jon Stewart of the mindful life—mainstreaming meditation and eco-responsibility in a fun, yet fundamentally serious manner. “Walk the Talk Show with Waylon Lewis” (named Top 10 Green Videos in US by MNN) has featured Marianne Williamson, Gov. Howard Dean, Gov. John Hickenlooper, Senator Cory Booker, Deepak Chopra, Bill McKibben, Paul Hawken, Michael Pollan, Dr. Andrew Weil, Alice Walker, Seane Corn, John Friend, Byron Katie, Sharon Salzberg, Sister Helen Prejean, Robert Thurman, Ken Wilber & 300 others. elephantjournal.com—100% independent—has been named to 40 top 10 lists nationally and swept the recent Westword Web Awards. Connect on facebook.com/elephantjournal and twitter.com/elephantjournal (#1 in US for #green two years running). To contribute an article, email write[at]elephantjournal.com. His first two books are “Things I Would Like to Do with You,” “It’s Never too Late to Fall in Love with your Life.”

Short Bio:

Waylon Lewis is a “Dharma Brat,” or second generation Buddhist. Founder of elephantjournal.com and host of the Top 10 US Green Video Series “Walk the Talk Show with Waylon Lewis,” he’s interviewed Seane Corn, Bill McKibben, Alice Walker, Michael Franti, Deepak Chopra, Michael Pollan, Amy Goodman, Chris Sharma, Terry Tempest Williams, Dr. Andrew Weil and hundreds of others. Named Treehugger’s Eco Ambassador & Changemaker, Discovery Network’s “Green Hero,” “Prominent Buddhist” by Shambhala Sun, Greatist’s 100 Influential People in Health & Fitness, & 5280’s Top Denver Single, Waylon is a mediocre climber, lazy yogi & 365-day bicycle commuter. Waylon’s first book, “Things I would like to do with You,” is about a new kind of independent-minded, genuine love. For more: @elephantjournal (top #green on twitter nationally two years running). Facebook.com/elephantjournal

Actually-Short Bio:

Waylon Lewis is the founder of Elephant Journal, the most-read mindful site in the world, and author of “Things I would like to do with You,” a story of modern love, commitment and loneliness from a Buddhist point of view. Host of Walk the Talk Show, named a top ten video series nationally, Waylon is a mediocre climber, lazy yogi & 365-day bicycle commuter.

Some Recent Press.

Dozens of celebs and influencers read, share, and contribute regularly to Elephant Journal.

Google+ partners with Elephant Journal’s Walk the Talk Show with Waylon Lewis:

elephantjournal.com made the list for top 30 health blogs!

The Denver Post features Waylon Lewis on the front page of their Lifestyle & Culture section.

The Denver Post features Waylon Lewis on the front page of their Lifestyle & Culture section.

The Denver Post’s Foodie Blog Colorado Table interviewed Waylon Lewis on the relaunch of Walk the Talk Show with Waylon Lewis and why organics and mindful living is important to everyday life.

The Denver Post’s Foodie Blog Colorado Table interviewed Waylon Lewis on the relaunch of Walk the Talk Show with Waylon Lewis and why organics and mindful living is important to everyday life.

Waylon Lewis on Bay Area’s KSRO The Drive Radio Show re Whole Foods, Health Care & Equal Rights.

Waylon Lewis on Bay Area’s KSRO The Drive Radio Show re Whole Foods, Health Care & Equal Rights.

The Greatist: Top 60 Must-Read Health & Fitness Blogs for 2012

elephantjournal.com: Happiness & Mental Health, #50

24. Waylon Lewis Happiness, Founder of Elephantjournal.com

24. Waylon Lewis Happiness, Founder of Elephantjournal.com

Raised as a Buddhist, Waylon Lewis never forgot his roots. After earning a degree in communications from Boston University, Lewis founded Elephantmagazine, which has since become Elephantjournal.com. This website is the go-to guide for the mindful life, including sustainability and spirituality. With his dedicated team, Lewis helps people live happy, meaningful lives through simple choices.

Click to read the full interview of Tricycle Magazine’s Connect with the World: Q&A With Waylon Lewis

Mother Nature Network speaks with Waylon Lewis: New media pioneer, lazy yogi & elephant lover. Read the full interview over at MNN.com.

Epic win! Waylon and elephantjournal.com won 3.5 Westword #Webawards at the Denver Westword Web Awards (nobody else won more than one, but we don’t like to brag).

UPDATE: Waylon Lewis: What the World Needs Now: A Green Jon Stewart was featured on the home page of Huffington Post, read my millions daily. Also featured in ‘Most popular’ sidebar, which is included beside every single article on Huffington Post. Many of Waylon Lewis’ articles for Huffington Post have been highlighted on their GREEN or LIVING page, as was this one.

UPDATE: Waylon Lewis, ‘eco bachelor,’ was named Top Single by Denver’s 5280 magazine. Here’s “9 things you didn’t know about Waylon Lewis.”

elephantjournal.com staff, including editor Waylon Lewis, were recently featured in an ecofashion company’s catalog. Click here for photos.

Many of the below press mentions of elephant concern our magazine, elephant journal, which officially went exclusively paperless on January 1st of 2009. Many concern our founding editor-in-chief, yours truly, Waylon Lewis. And many concern our talk show, “elevision,” which I also host.

First, my BIO as it appears on my Huffington Post profile, for those who should need it. [All of my articles and videos for The Huffington Post can be found here: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/waylon-lewis . You can subscribe, free, to my posts here].

PHOTO:

The above images are all low-rez, available for online use with permission. If you need high-rez, just ask.

elephantjournal.com editor-in-chief Waylon Lewis (yours truly) penned the below feature article more than a decade ago, now, when I was still studying magazine journalism at Boston University. I was 21, or thereabouts. I wrote this under the patient guidance of one of my editor mentors, Melvin McLeod, for The Shambhala Sun, a leading Buddhist magazine. While it was (to put it politely) riddled with errors, it nevertheless captured something about a young, new, first generation of Buddhists born and bred as Americans.

elephantjournal.com editor-in-chief Waylon Lewis (yours truly) penned the below feature article more than a decade ago, now, when I was still studying magazine journalism at Boston University. I was 21, or thereabouts. I wrote this under the patient guidance of one of my editor mentors, Melvin McLeod, for The Shambhala Sun, a leading Buddhist magazine. While it was (to put it politely) riddled with errors, it nevertheless captured something about a young, new, first generation of Buddhists born and bred as Americans.

Dharma Brats

by Waylon Lewis

Emily King was walking down the slate-grey sidewalks of downtown Boston, on her way to the Trident Cafe on Newbury Street. It was a humid day, and the men and women who walked the streets wore shorts and tee-shirts and many, especially the children, had ice-cream cones in hand.

The young journalist who waited for her at the cafe was similar to Emily in many ways: he was 20 years old, a college student in Boston, an aspiring writer, and another “dharma brat,” raised in an American family devoted to the practice of an Eastern religion.

Emily’s family, he knew, had nearly 300-year-d roots in Boston, and like his own parents, hers had discovered and embraced an Eastern spiritual discipline in the turbulence of the 1960’s and early ’70’s.

He had already interviewed a young man in Santa Fe who had grown up within the confines of Zen Center in Rochester, New York; another who was raised in a family practising Tibetan Buddhism and now works for Chemical Bank in New York City, and a young man who decided to follow his parents and become a Buddhist himself.

Each of their stories was different, each felt their character affected in different ways by their unusual households, and each found their way through childhood, school and the beginnings of adulthood quite differently. But they shared something unique, something rooted in their birth and upbringing that lends them an attitude or view not found in others of their generation.

Emily, Josh, Jason and Noel are children bred of two greater parents: America and an Eastern spiritual discipline. They represent the first complete meeting of West and East, of America and dharma.

“Hi,” Emily had said, when she found me at a table near the street-facing windows, in the smoking section.

“Hello!,” I said, and stood and smiled, shaking her hand and then waving to the waitress passing in the distance. “Another cup? Thanks.”

I received my refill and Emily, a tall, pretty and somewhat pale girl with shoulder-length brown hair, ordered a little pot of tea. The cafe, despite the large windows, was somewhat dark and cool, full of books and paintings, people and smoke.

It was yoga practice that had brought Emily’s parents together in the wake of Vietnam, Nixon and the exploration of alternative lifestyles. Dave and Martha King raised Emily in Brookline, an affluent section of Boston, after settling down from, as Dave King puts it, “a life of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.” Dave set to work at a pizza house, while Martha set her sights somewhat higher.

“Too high, I thought,” Dave remembers with a smile. “Martha wanted to start an ecological furniture business. I said, ‘A what?’ And, ‘With what money?’ and figured my minimum wage job at the pizza joint would be paying the bills for Emily, who was born only a few months later on.”

Twenty years later, when Dave and Martha’s grown-up girl visits them in Brookline, she comes home to a sprawling mansion and a garage housing two elegant cars. The furniture business has flourished. Martha is, as she puts it, a “rich Liberal, once-hippie, CEO wife-and-mother” and could be considered, at 52 years old, an archetype of the ’60’s generation grown up.

But some things remain the same for Dave and Martha and other aging, once-rebellious baby-boomers. Martha and Dave still, as for the last 22 years, begin each morning with 30 minutes of yoga practice.“Well, it really wasn’t strange to grow up the way I did,” Emily told me. “Dave and Martha made good money; we had a nice house, nice cars, went to the symphony and for picnics at Marblehead beach each summer.” Her parents practiced yoga each day, went to lectures by “this teacher or that,” had books about yoga, magazines, Eastern pictures on the wall, but “it all blended in. Only when I was older did I begin to assess yoga in a more personal, critical, and objective way.”

For most of her teenage years Emily observed a respectful distance from her parent’s practice of yoga. Her friends at school took “a light-hearted, curious point of view”-just wanting to know if she “did drugs or voodoothey thought it was a bit trippy, love-and-lighty.” Then, a funny thing happened just before Emily left for college at Wellesley in 1992.

“In preparing to say goodbye to my childhood, to living with mom and dad and pooch, I found that leaving also meant a departure from something more subtle, even fundamental in my old life. I decided that before I said goodbye to yoga, I wanted to know if I really knew what it was. And in reading and practicing a little of it, and talking with other children of my parents’ yoga friends, I made or discovered a sharp connection to yoga, one that I didn’t want to leave, but rather deepen.”

Yoga became a personal spiritual path that Emily is committed to even while at school, if only through reading or visiting her parents in Brookline. Her daily effort to “maintain a sense of joy and goodness” is rooted in her yogic practice.

“Yoga is obviously very body-oriented,” she said, leaning her tall frame against the cafe table. “Its exercises can help to synchronize one’s body with one’s spirit. There’s lots to it-it is almost silly to try to summarize yoga in a few sentences. But personally it serves as a practice to connect my crazy life with something constructive and spiritual.”

Illustrating her belief that yoga is something to be practiced genuinely and thoroughly, and not briefly discussed, she mentions that Jane Fonda and others have done exercise videos for it. “It’s somewhat popularized, which is good, but it can be bad, too,” she says, “if people approach it frivolously-just wanting ‘the goods’ without any respect. Then it just becomes more self-help, spiritual fluff.”

Yoga is no longer just something that she grew up with, something that her parents did, no longer “just an influence, in the way a hobby or ordinary passion is.” Emily now practices nearly every day for one to three hours. If she doesn’t have time, “I read, or do a few quick stretches in the morning, whatever will connect me to yoga on that day,” she says.

“You see, it’s become the essential way for me to communicate with IT.” Emily smiles when asked what she means by IT, then shrugs her shoulders. “That’s what the whole world has been arguing about for centuries: the definition and rights to IT. It’s personal, anyway. My practice of yoga is how I can try to deal with all my problems and stress and grow in a genuine, healthy, confident way. It’s just about being a curious, cheerful human.

“I really want to emphasize-and this doesn’t make me a very good interviewee-,” she grins, “that I don’t want to just talk about yoga. I want to say how I really am American too, not in the sense that I’m afraid of being black-listed or something, but that both worlds have continuously affected me in my life. I approach life as an American from a more independent, clear point of view, I think, and I approach yoga practice with all of my very American expectations, desires and problems.”

Emily finished her little pot of tea, and I finished my coffee. As she prepared to leave, grabbing her backpack and getting up to look at some magazines, I gathered my previous interviews and, with papers laid out all around me, a cup of coffee and a friend’s Powerbook, began working.

Emily, however, had not yet left the cafe and returned to say goodbye.

She saw all the papers. “Are these the other interviews?,” she asked.

Emily sat down again on her side of the now cluttered table. “Do you mind if I read one while you write?,” she asked. “I have an hour-and-a-half before the Red Sox game at Fenway.”

Pleasantly surprised, I handed her a small stack of papers. “This is the one with Josh Schrei,” I told her. “He’s in Santa Fe, New Mexico now, but he grew up with his parents at the Rochester Zen Center.”Emily ordered another pot of tea and began reading, while I set to typing, smoking, drinking coffee and pacing around the street just outside. It’s a tough enough gig to be a “curious, cheerful human,” as Emily put it, tougher still when you’ve got an article to write.

In 1970, when Josh Schrei was born, his parents left their politically active life on the Oberlin campus, leading sit-ins and protests against the war in Vietnam, for an austere life of meditation and study at Philip Kapleau’s new Zen Center.

The center was situated like an island in a pond, its acres set in the midst of the industrial city of Rochester, New York. Josh grew up playing hide-and-go-seek with the children of other staff members in the beautiful Japanese gardens and halls of the center’s two main houses. He learned about meditation, enlightenment, the Buddha, and the “outside world” from within the sprawling confines of Zen Center. It was as wonderful a childhood as it was disillusioning.

His parents were among the few lay resident staff members at Zen Center. For the first years of the center, Josh told me, the staff was painfully ambivalent regarding the status of the center-whether to be purely monastic or more open, with resident families and visitors. Zen Center was a sort of spiritual New World, a place where students hoped to escape what they considered to be a world full of corruption, suffering and aggression. This attitude, a “dualistic attitude of nirvana versus samsara,” was also directed towards the children at Zen Center.

“We epitomized their dilemma, you see,” Josh says. “Children weren’t there for the same reasons everybody else was. We couldn’t meditate because the adults were hit by a stick if they fidgeted,” as is the zen tradition, “and of course they didn’t want to hit a jumpy kid with the stick.” Josh, his best friend Jake, and the other children at the center were also prohibited from eating breakfast or lunch with the adult students, as these meals were taken in formal zen style, kneeling on cushions on the floor, in complete silence except for Buddhist chants.But Josh also identified with and found enthusiasm for much of the zen way of life. On his seventh birthday a zen student gave him one of the sticks used to hit a restless meditator. Inscribed on the stick was what little Josh considered his first koan: “Be kind to everyone.” He also received a zen monastic meditation manual, and in the manner of all “my other games, began training myself to be a buddha.” This was his only goal as a child.

Josh’s years in public school were “remarkably free of animosity.” The only, admittedly minor, exception was when at lunch-time a “zen clique formed,” taking over an entire table, because “we were all vegetarian. Growing up, vegetarianism was the most concrete evidence of my being Buddhist. And it was considered strange, weird-we had to justify ourselves on numerous occasions.”

When Josh was 13 years old his parents, courtesy of Zen Center, set off on a pilgrimage to see Asia’s notable Buddhist historical sites. As Josh was a year ahead in school, he was able to take the year off and join them. The trip was “wonderful, perfect”; they traveled through India and Sri Lanka and saw Bodhgaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment.

His parents, now zen teachers in their own right, moved with Josh to Santa Fe, New Mexico to lead a new group there. These were his teenage years, and free from Zen Center, bored in Santa Fe, Josh learned to love and explore the mountains and forests, Native American traditions, and, when he was older, some of the drugs of this southwestern state. “The zen I grew up with was so ethereal,” Josh recalls. “I needed something different, something to bring me back to earth.”

When he was 16 years old he made an enthusiastic connection to Tibetan Buddhism. “To see a lama laughing and giggling, radiating a sense of joy, struck a chord in me,” Josh said. This exploration of Tibetan Buddhism coincided with “a serious falling-out” between his parents and Philip Kapleau, still leader of Zen Center. Josh’s father had begun incorporating other forms of Buddhism into his teachings, and that, along with a peer’s underhanded competition for a leadership position, resulted in an angry letter from Kapleau. Josh’s father, the letter said, would never teach for the center again.

“Americans have a strange relationship with teachers in general. It’s like-,” Josh smiled, “-in the “Life of Brian,” the Monty Python film, when Jesus is talking to this crowd. He says, ‘Don’t look towards me, you’re all individuals. You can all think for yourselves!’ and the crowd repeats, ‘We’re all individuals, we can think for ourselves…’ People like to put a teacher on a pedestal-‘the guru is everything’-and if not, then they blame the guru. There’s some sense of projection. We hurl ourselves at teachers-‘I finally found the one who’s going to change my life’-then when it doesn’t happen the guru is suddenly seen as evil.”

Josh still appreciates his upbringing. “Zen is so strict and austere, yet at the heart of its teaching is spontaneity. There’s a zen koan that says, ‘Look-the world is vast and wide; why do you put the monk’s robe on at the sound of the bell?,’ and to me that is the basic question of zen altogether. If the world is without substance, why decide to live with so many rules and regulations? I wonder about that.”

The zen spirit of “constant questioning” can be forgotten, however. All too often, Josh relates, there was “never any middle ground. Zen can be so full of ideals; you have to be so perfect. I was constantly surrounded by ideas of perfection and spiritual enlightenment. I was infused with this idea since birth that I had to be perfect.”

Meditation is now a helpful element in Josh’s daily life. He tries to practice meditation consistently, in a style that includes elements of martial arts and Tibetan meditations, as well as zen. It is basic, simple and informal: “You observe your thoughts as passing like clouds through the sky,” Josh says. “With the world the way it is these days, any time you can take five or twenty minutes to be with yourself and relax, let go and not think about anything is extremely valuable. This world is crazy-we’re constantly being bombarded by sensory stimulation, we’re always in a hurry…

“Principles of compassion, awareness, loving-kindness, emptiness and impermanence are fundamental Buddhist ways of seeing the world,” and have been with Josh “in a visceral, subconscious way” since he was very young.

For the past two years, Josh has been touring a one-man show called “Kathmandu,” drawing heavily on his childhood experiences at Zen Center. Zen, he says, is so much “a part of who I am that I don’t think I could ever escape it.”

Finished reading my hasty transcriptions of the interview with Josh, Emily looks up and says, “Hey, that was really great! I think he’s a pretty thoughtful, good guy. Do you have any more interviews with you?”

“Sure,” I said, “I’ve got my interview with Jason, who’s in New York City. He’s hardly involved with Buddhism actively-his every hour is spent in Chemical Bank.”

“I don’t need to get to the Red Sox game for an hour.”

Jason Kiefer sits in a mostly darkened office-it’s nearly 9 p.m.-in one of the countless skyscrapers in Manhattan’s concrete-and-steel forest. Dressed in a shirt that three hours ago held a tie, and well-ironed but now rumpled dress pants, he finishes the remnants of a sushi dinner that was delivered more than an hour ago. Jason is somewhat pale; he has spent the last few years, sometimes averaging 12 hours a day, in the office of Chemical Securities market analysis division.

Jason at 24 years has completed two of the earliest, most rigorous stages on Chemical’s ladder, and is on his way to one of the top business schools in America, preferably Harvard or Stanford. He is the classic Hollywood picture of “a fine young man plugging away on Wall Street.

Busy as he is, Jason may think little about the American Buddhism of his childhood; nevertheless, his “personal philosophy is still based upon Buddhism. It’s what I grew up with.” Buddhism-its ideas, practices and personalities-were “all I knew.”

But Jason says, “I’ve always been anti-religious, at least in terms of theistic religions. You could call me anti-spiritual. I don’t believe in anything that science can’t explain, or acknowledges it can’t explain. I remember when I was four years old going up to my mother and asking, ‘If God invented the world, who invented God?’ She didn’t know the answer-and I’d still like to know.” In first grade, Jason was “the first in the history of the school to be exempted from religion class.” He grins, then asks me to hold on a minute as he takes an incoming call.

Meditation never appealed to Jason. First of all, he says, it was hard, boring work. Second, he has not seen how meditation applies to what he feels he misses most in his life: “Glee. There are too few times in my life that I feel completely, irrationally happy. Meditation is about examining and understanding the mind, and passion, happiness, is best when you don’t know, or care, why you’re happy.”

What his upbringing has given him, Jason says, is an understanding that pain, confusion and depression are rooted in his own mind, and therefore are workable. “I understand that suffering, at least mental suffering, isn’t somebody else’s fault. So I can drop it, or at least try to.”

What Jason is doing now, of course, requires a whole-hearted commitment of time and energy. “This is a world that few Buddhists enter,” Jason notes. “I don’t know why. All I know is that I have this ambition. I don’t know if Buddhism can give you that ambition, create it. It’s a source of energy and joy. I like what I do, though I wouldn’t do it if there wasn’t any money in it.”

Jason and I say goodnight and he gathers his things to leave the office. He’s been there since 7:30 a.m. and needs to get to bed. Tomorrow is yet another 12-hour day in the office of Chemical Securities Market Analysis Division in New York, New York.

“I like that one,” Emily says. “But poor guy, it sounds so boooring.”

“But he likes it,” I say, glad that she liked it. “Well, do you want to read another?”

“Yes,” she replies, “But-of-course. Who is this one of?”

“His name is Noel McLellan. He grew up in Boulder, Colorado and is now Buddhist himself. Hope you like it,” I say, and resume the task of transcription, from tape to paper to Macintosh.

Noel McLellan takes a rare hour off from his studies at the University of Colorado and his duties as assistant bookstore manager at a popular cafe downtown. He sits on the red-carpeted stairway that leads from the reception hall to the residents’ apartments above at Marpa House, a large Spanish-style villa and for more than twenty years a Buddhist community apartment house.

It was here in Boulder that Tibetan Buddhism as taught by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche first took root, here that his parents met and married, and here that Noel was born.

It was quite a scene in Boulder in those days. Many of Trungpa Rinpoche’s students, at his urging, cut their long hair and gave up tie-dye and drugs for suits, jobs and families. As meditation centers sprang up nation-wide, Boulder itself was consumed by the beginnings of The Naropa Institute, a Buddhist-inspired college where, as Trungpa Rinpoche put it, “East and West meet and sparks can fly.”

More than 200 people showed up for Naropa’s first shoe-string summer, featuring Trungpa Rinpoche and Ram Dass. The Beats also lent a hand-Allen Ginseberg, Gary Snyder, William Burroughs and many other poets and artists came to Naropa, where Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman founded the Jack Kerouac School of Disemboded Poetics.

Noel is one of a core group of children whose age reflects the length of Buddhism’s stay in America, and so is called a “dharma brat” by some, in off-handed reference to a Kerouac novel. Dharma is a word that refers to the teachings of the Buddha. Brat, of course, refers to the fact that while most students take a circuitous route towards the buddhadharma, these children were born and raised in the community-and could therefore take their rich, peculiar existence for granted.

Asked what he thought was unique about growing up in a Buddhist family, Noel pauses and says, “It’s difficult to say because I don’t have anything to compare it to. But I think there was always some sense of trust that I don’t see so much elsewhere. A kind of faith. But they never pushed Buddhism on me. I did have a general sense of being Buddhist and when, one day, a friend came over and asked if I believed in God, I knew we didn’t, so I said ‘no.’

“He immediately began telling me I was going to go to hell, and I freaked out. I asked my parents, and they said, ‘No, no, don’t worry, you aren’t going to go to hell.’ But basically they really did their thing and left me alone.”

And here Noel mentions the “atmosphere” that was present throughout his childhood. “I remember always being very bored” by events at the center in Boulder. “Nothing much happened. It was very quiet. But at the same time, people were often very dressed up, and there was this energy, this richness, this power to it-it was always very charged.”

Asked about the primary difference between the Buddhist elementary school he went to and the public junior high school he later attended, Noel replies after a pause.

“Well, a story I always tell,” Noel says with a smile, “is when one day I had to bring Mr. Visser, our principal, a note. I think I was in some kind of trouble at the time, which at public school would mean you’d go to the principal’s office and be treated like a hassle. Well, Mr. Visser came out of his office and smiled, and bowed to me. I didn’t think much about it at the time, but later on I realized it was such a sign of respect, for my potential as a future warrior and good person, good Buddhist.”

Now that Noel is an adult, and has chosen to follow the Buddhist path of his own accord, he is confronted with the task of understanding how the buddhadharma could guide his life. “I’ve been thinking a lot about the whole idea of ambition. Sometimes when I’m at school I’ll look around, and I wonder what everyone is doing there. Everyone is there out of some sense of wanting to make it. That’s the high ideal of American society, but I don’t know if I care whether I make a ton of money…”

Noel is firmly dedicated to the path he has chosen: he practices meditation and studies Buddhism with the same mix of faith and relaxation that his parents showed him as a child. His path is purely a personal one, and so he views his life now and his future in the context of the teachings.

“We’re a unique bunch of characters to write about,” she says and smiles.

I smile too, appreciating Emily’s positive response, and the more salient fact that Emily, Josh, Jason and Noel’s experiences do seem unique: not just different, but worthwhile, vital and urgent in this time of change, suffering, progress and upheaval.

But as I sit contemplating that, Emily has asked me a question, which I ask her to repeat. “Want to join me and my friends at the Red Sox game?” Emily has asked.

“Yes!” I say.It was one of the first games of the season. Fenway packed, the day still sunny, the atmosphere one of baseball at its best. Thoughts of my interviews with Jason, Noel, Josh and Emily floated through my mind (like passing clouds, as Josh had said). I looked around and wondered if indeed zen or Tibetan Buddhism or yoga have anything to contribute to such a crowd as this. I can recognize in the faces of the little children, of the bare-chested, tipsy men, of the mothers and even the ball-players, the humor, thoughtfulness, joy, compassion, boredom that each of my interviewees manifested.

I looked at Emily, thoroughly enjoying herself with her friends, as at home in classic Americana as she is with her spiritual discipline. And so it is with these “dharma brats.”

They are clearly a part of Generation X-they watch MTV, snowboard, study and socialize, experiment (perhaps) with drugs, dream of being rich, famous, falling in love. But there is another, once-exotic foreign influence in their lives. Whether yoga, zen or Tibetan Buddhism, their path is not only temporal but spiritual, and so while enjoying “Reality Bites” on video with friends and popcorn, they may see with different eyes and feel with different hearts.

Jason, Emily, Josh, Noel and young people like them unite two distinct influences-for centuries so separate-on a personal, fundamental, thorough level. If East meets West, and the sparks can fly, Noel, Jason, Josh, Emily and the rest of this rare generation are now the embodiment of that spark.Born in Boulder, Colorado, Waylon Lewis is a journalism student at Boston University and is himself a “dharma brat.”

A look back at elephant’s origins, circa 2002. We were featured in Boulder, Colorado’s paper of record, the Daily Camera when we first started out, back when I was (gasp) 28 years old.

Duo targets yoga community with new magazine

Yoga in the Rockies [which became elephant magazine, then elephant journal] launches in BoulderBy Chris Taylor-Shaut, For the Daily Camera ~ September 23, 2002

Two aspiring yogis realized their dream this month with the first publication of Yoga in the Rockies.

Travis Robinson, publisher, and Waylon Lewis, editor, are the partners behind this new, free Boulder-based bimonthly magazine. Despite maxing out their credit cards and cashing out their savings to put out the first issue, they are enthusiastic about increasing yoga consciousness in the community and optimistic about their magazine’s success.

“We look at profitability a little differently than most American business models,” Robinson said. “We’re incorporating a care-first business model rather than money first. You care, you share, you give. And you will receive.”

This Eastern-influenced business philosophy helps the partners transcend the currently dwindling print media economy, Robinson said.

Magazine advertising revenue rose only 2.7 percent in August 2002 and saw losses for nearly two years prior, according to Reuters. Robinson and Lewis’ publication pulled in an estimated $5,000 in advertising revenues while the two paid roughly $10,000 in production costs for the first issue. These figures don’t include salary or overhead. Their eight-person staff is working for free.

There is also an abundance of alternative media outlets in the United States and Boulder media markets, leaving little room for a new magazine. Lewis cited Yoga Journal, Nexus and the Mountain Gazette as Yoga in the Rockies’ primary competition.

Ravi Dyhema, publisher of Nexus magazine and a yoga teacher of 18 years, said he is not sure the yoga market is big enough to support a magazine.

“Many magazines in this area have tried to extend the market and gone under,” he said.

He said he doesn’t feel threatened by the magazine and considers Robinson and Lewis as colleagues rather than competitors.

Lewis said he thinks their publication will fill an untouched niche in the market. They printed 25,000 copies of the first issue.

“The print media market is bad, but the yoga market is booming,” he said. “We’re grassroots. And our magazine will connect yoga students with all of the word-of-mouth organizations, classes and studios people wouldn’t otherwise know about.”

The partners have created a database of more than 700 studios, many of which can’t be found in the phone book, they said. Lewis added that other yoga and new age journals are trying to sell spirituality, while Yoga in the Rockies is appealing to a way of life.

Lewis and Robinson said they are also optimistic because of the response they have received from the community.

“People want to be a part of this,” Lewis said. “Companies and studios want to know how they can get involved. The next issue will probably be about 25 percent bigger.”

I was quoted briefly in an articleby Michael Sandrock, about Buddhist teacher Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, back in ’05:

Sandrock: Buddhist leader goes the distance

Sunday, October 23, 2005

RED FEATHER LAKES — As I run through the “Valley of Death” on this warm August morning, I was glad to have Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, Misty Cech and several other runners a step ahead of me. We were running on a dirt road winding through pine forests and lush meadows in the rolling hill country northwest of Fort Collins, heading toward the finish of a 50K run that would end at the Great Stupa at the Shambhala Mountain Center.

Sakyong Mipham is the renowned teacher and spiritual leader of the international Shambhala community, and, since the publication of “Turning Your Mind Into an Ally” in 2004, a best-selling author. He has also turned into a serious marathoner since taking up running just over three years ago, as I found out during this run.

It was the inaugural Great Stupa Run, and there are tentative plans to hold a shorter trail race at the mountain retreat next summer.

“I enjoy running,” the Sakyong (an honorary Tibetan term meaning “Earth Protector”) said as we started out just past 5 a.m. “We wanted to do a race longer than the marathon distance before New York. But the schedule did not work out, and we decided to hold our own 50K.”

On Nov. 6 in New York City, the Sakyong will run his fourth marathon, in part to raise money for the Konchok Foundation, which wants to rebuild a monastic and education center in Tibet’s Surmang Valley. Cech, a local yoga instructor and naturopath, as well as an excellent runner, will accompany him in New York, along with her husband, Eric, and training partners Nick Trautz and Jon Pratt.

Sakyong Mipham, 42, has a personal best of 3 hours, 9 minutes in the marathon, which he ran in Edmonton last year. He also has completed California’s Big Sur Marathon and the venerable Boston Marathon. The Sakyong is well-known in Boulder because of his position as head of Shambhala and because his father, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, founded Naropa University and is credited with helping bring Tibetan Buddhism to the West.

On this long morning run, we are not talking about Buddhist spirituality, however, but rather running and writing. The Sakyong’s second book, “Ruling Your World: Ancient Strategies for Modern Life” (Morgan Books), is being released this week, and on Friday, he kicks off a national book tour with a public talk at the United Methodist Church of Boulder.

“This is a beautiful loop,” the Sakyong says as we head out in the early-morning darkness. “We did a 23-mile run here. It climbs to 9,000 feet and has some wonderful views. We started at 6 (a.m.) on that run, and it was very hot by the end. So we wanted to start earlier today.”The run is indeed beautiful. We head off at a surpassingly solid pace, and as we run along, the sky brightens as the sunrise climbs over the hills to the east. By 16 miles, through a long valley called jokingly (I think) the “Valley of Death,” I am feeling that gradual fatigue that sneaks unannounced into leg muscles that are working past their limit, and I am glad we started in the cold and dark of the early morning.

The run was like long runs everywhere, with small talk, digressions, pit stops and breaks to adjust shoes. The difference from most long runs was the excellent support crew we had, with water, oranges and energy drinks appearing whenever one of us raised a hand.

Slowly, I found myself falling off the back of the pack, running along with Eric. Watching Sakyong Mipham run ahead of us, he says, “Rinpoche is one of those extremely talented individuals. He’s been running only a short time and is a natural at it.”

Waylon Lewis, publisher of the Boulder-based magazine Elephant, agrees. Lewis has known Sakyong Mipham, who was born in India and grew up in part in Boulder, since they were children.

“The Sakyong has been an athlete since he was a kid,” Lewis said. “He has at various times excelled at Zen archery, weightlifting, horsemanship and golf. It was a matter of time before he ran into running, so to speak.”

Just past 20 miles, near the small town of Red Feather Lakes, I realize I will not make the entire 50K. It is a happy realization, as I know I will be able to sit down soon, and finally, at 22 miles after a steep downhill, I am forced to a walk, then a stop.

When I gratefully pile into the support vehicle and gobble down oranges, the Sakyong’s form has not changed. He is still smooth and efficient, reminding me of Toshihiko Seko, the great Japanese marathoner. We follow the runners in the car, and as they make the final climb toward the Great Stupa and the end of their nearly 32-mile run, both sides of the dirt road are lined with guests and teachers from the Shambhala Center.

A chant of “KI KI, SO SO!” rises up from the spectators lining the road, part of the traditional Tibetan victory cry, Lewis later explains. The chant goes on as the runners pass by, sending a chill up my spine. At the Stupa, I jump out and join the runners and the many cheering children, and we all circle the Stupa.

The Sakyong runs in with a flag, and when he finishes, he takes a scarf and tosses it over the arm of the giant Buddha that fills much of the Stupa’s inner space. After accepting congratulations, the Sakyong leaves. The next time I see him, he is out of running clothes and sitting dignified in the orange and red brocade that signify his position as head of Shambhala.

Listening to him speak, it is clear that Sakyong Mipham is a spiritual leader for the 21st century, someone with centuries of Tibetan Buddhist teaching and traditions behind him (In fact, he is considered the incarnation of Mipham the Great, called by Elephant’s Lewis “Tibet’s Leonardo da Vinci”), yet well-versed in the modern world. He is even a Broncos fan.

Author and scholar, poet and teacher, it is nice that the Sakyong is also a long distance runner. What better person to show us how to bring together mind and body in these troubled times than a meditation master turned marathoner?

An article/review for the Shambhala Sunmagazine on growing up around Chogyam Trungpa.

elephant editor Waylon H. Lewis’ recent review of

Chögyam Trungpa’s first biography, in Shambhala Sun magazine.

Click image on right to read review.

The World of Chögyam Trungpa

Chögyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision

By Fabrice Midal

Shambhala Publications, 2004; 480pp.

Reviewed by Waylon H. Lewis

There are a few books that I’m always buying up in used bookstores and giving out to friends. Gift from the Sea. Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Anything by Pema Chödrön.

But if I were ever marooned on that proverbial desert island—as a Coloradoan, an eventuality I’m always planning for—there’s one book I’d bring: Chögyam Trungpa’sCutting Through Spiritual Materialism. And, oh, I’d sneak in one of those pocketbook versions of his seminal Meditation in Action, and tuck away Trungpa’s Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. And I’d have to grab Training the Mind, Trungpa’s teachings on, well, training the mind. Then, just to cover my bases—there’s not much to do on an island, you know—I’d bring the recent Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa—eight handsome volumes that alone weigh six pounds more than a marooned islander is normally allowed to bring along.

So I guess I’d have to leave ’em all behind, and bring just one, and that would be Fabrice Midal’s new biography of Chögyam Trungpa, titled, aptly, Chögyam Trungpa. Midal is a professor of philosophy at the University of Paris who, though a student in Trungpa Rinpoche’s Shambhala community, never met the man. So, while his book may not be filled with typical personal reminiscences (“Trungpa did this amazing thing that just blew my mind!”), it has just enough distance between subject and author to really see the breadth of Trungpa’s world.

Chögyam Trungpa was a Tibetan Buddhist teacher and king, of sorts, who fled his homeland in 1959. Leading 350 of his people across the snowy Himalayas, Trungpa found himself squarely, suddenly, in the twentieth century. It was a rude awakening—but one which the young Buddhist teacher embraced.

After meetings with the Dalai Lama and Thomas Merton in India, Trungpa journeyed to Oxford University on a scholarship. After struggling for some time to communicate the teachings of Buddhism—his Western students seemed mostly interested in his exotic caché—the young Trungpa left behind his monk’s robes and vows and eloped with a young English woman. Journeying to America, he would over the next seventeen years write a dozen bestselling Buddhist books, teach thousands of seminars, found scores of Buddhist centers, and establish the West’s first Buddhist-inspired university. He would pioneer the teaching of Tibetan Buddhism to the Western world, dressed to the nines (his hippie students soon followed suit) and communicating in the idiom of his students.

Here’s where Midal excels. While his biographical study is an official one, blessed by Trungpa’s widow, Lady Diana Mukpo, it is both frank and inspiring.

Midal covers every facet of this renaissance man—a man trained from birth in government, poetry, calligraphy, theater, dance, the buddhadharma—a man whose death at the premature age of forty-seven may have been due, in part, to an ever-present glass of saké, a man who took many lovers, was chauffeured in a black Mercedes, and, though paralyzed, rode a white Lipizzaner stallion.

But the man was not the myth. I grew up in Trungpa’s world, my young parents having met at a seminar of his (entitled “Crazy Wisdom”) in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in 1972. I was born on the day’s break between the two sessions of Naropa University’s first summer, in 1974. I took the bodhisattva vow, in which one dedicates one’s life to the welfare of others, with Trungpa. I attended his Shambhala Sun Summer Camps, in which we marched around singing, played capture the flag, and learned how to work with our own minds. By the age of ten I had been exposed to poetry, horsemanship, calligraphy, Zen archery, Japanese flower-arranging, and Zen dining.

But for all its strange, magical wonder, the world in which I grew up has remained largely unreported. Trungpa’s own books, while profound and poignant, revolve around timeless Buddhist teachings on life, mind, art, poetry. And so it was that, from the first page—literally, Midal’s table of contents—I found this fast-fading world rise up again before my eyes. I felt like crying and smiling simultaneously—what Trungpa referred to as the best of human emotions.

Chögyam Trungpa is largely remembered, these days, as a wild, extraordinary Buddhist teacher, a sort of spiritual rock star. But the man I knew was no Crazy Wisdom guru. He was boring, frankly. As a child I loved his Regent, Ösel Tendzin. I loved the Karmapa. I loved just about everybody. But Trungpa? I loved him, sure, in the way you love your grandfather. He was sweet, and mild, and talked excruciatingly slowly in that strange, high British accent of his, and he frequently put me to sleep, curled up in my mother’s lap and a meditation cushion. Nothing ever seemed to happen around him. I saw him all the time—he was in a very real sense part of my family, or I part of his—he was the center of the wonderful world in which I found myself—but he was nothing special.

And that’s what makes his legacy so extraordinary. Extra-ordinary. For the teachings of Buddhism are, as he termed it, nontheistic. There is no god. Buddha was himself a human being. When it comes down to it, you have to help yourself. It’s not a cynical teaching—it, like Trungpa, is achingly sweet, sad, cheerful. And I miss him, and I’ll never forgive him for dying so young. But while I may not forgive, I won’t forget—thanks to Midal’s work—a biography that, like its subject, walks a razor’s edge between East and West, spiritual and temporal, Crazy Wisdom and ordinary mind.

Waylon H. Lewis is the editor and founder of elephant, a Rocky Mountain magazine covering yoga, organics, independent business, green living, buddhadharma, and the arts.

The World of Chögyam Trungpa, Shambhala Sun, September 2006.

To order this copy of the Shambhala Sun, click here.

An early review of one of our first public interview talk shows, by the Daily Camera.

Photo by Sammy Dallal

Elephant Journal’s Waylon Lewis, left, interviews poet Anne Waldman on the back porch of the Trident Cafe as part of a recent “ele:vision” taping.Elephant Journal’s live talk show focuses on ‘the mindful life’

By Marisa Ware For the Camera

Friday, July 6, 2007This summer, Boulder’s Elephant Journal is starting a show it hopes will help change the world.

Every Thursday night behind the Trident Cafe, Elephant hosts its new “homegrown talk show” called “ele:vision.”

The free show, which consists of two 15-minute interviews along with a musical guest, was inspired by the style and popularity of “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart.” The interviews will focus on the same themes as the magazine — yoga, sustainability, organics and conscious consumerism, as well as many other things that make up what Elephant calls “the mindful life.”

“More people watch TV than read magazines,” said Waylon Lewis, editor and founder of Elephant. “Ultimately our goal is to get the attention of some cable channel and really try to influence the direction of the world. We’d like to do for the mindful life what Jon Stewart did for politics: take something that’s pretty off-putting and not that interesting and make it fun and accessible and get people involved.”

So far, “”ele:vision” has hosted such big names as John Perkins, author of the bestselling book “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man,” and Anne Waldman, beat poetess and co-founder of Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. In addition to the well-known guests, “ele:vision” aims to highlight local businesses and professionals whose work runs in the mindful vein.

“It’s a pretty wide range of people, from renowned authors to local heroes and activists — just people who have missions they’re trying to carry out to change the world,” said Heather Mueller, event organizer for “ele:vision.”

One of the recent guests, Naropa teacher and writer Andrew Holecek, was invited to the show to discuss death and dying from a Buddhist perspective.

“I did ‘ele:vision’ to help get the word out that when teachings on death and dying are approached in a healthy, sane way, they not only help you prepare for your own death, but they also help you live more completely,” Holecek said. “I thought Waylon did a decent job with making the topic interesting without watering it down or making it too foreboding for the people who were there.”

“ele:vision” interviews have also addressed issues such as economic globalization and political activism, as well as environmental problems like global warming. In addition to providing education and entertainment to the audience, “ele:vision” intends to create a fun social atmosphere where like-minded people can get together, relax, and be inspired, Mueller said.

“If we sit in our offices or our rooms or our own little places, we get isolated and it’s easier to feel like there’s nothing we can do,” said audience member Ward Luthi. “I think we need to have that community of other people around us to feed off the energy that is there. It’s a very positive and powerful thing.”

In order to reach more people, every “ele:vision” interview is filmed and posted on Elephant’s Web site, http://www.iamelephant.com. The live tapings have been filling up the back patio of Trident with an eclectic crowd ranging from people in their early 20s to those in their late 80s.

“On a certain level this has nothing to do with Elephant,” Lewis said. “Our world is in an emergency situation and the media and entertainment are the quickest ways to turn the wheel. It doesn’t matter who gets the message out, just as long as someone does it and does it quickly.”Perkins, author of the bestselling book “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man,” and Anne Waldman, beat poetess and co-founder of Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. In addition to the well-known guests, “ele:vision” aims to highlight local businesses and professionals whose work runs in the mindful vein.

“It’s a pretty wide range of people, from renowned authors to local heroes and activists — just people who have missions they’re trying to carry out to change the world,” said Heather Mueller, event organizer for “ele:vision.”

Dorris: Mindful talk

By Jennie Dorris

Thursday, June 21, 2007I recently packed everything I owned into boxes and then, a day later, unpacked them to find that I had lost nearly everything. Every time you move you may label your boxes with saint-like intentions but you end unpacking them and can’t find your hammer or your friend’s wedding invitation.

There was one thing, however, I kept careful tabs on. And that’s my letter from Gigi. Gigi is an 81-year-old reader who writes to me sometimes — usually she’s too busy doing Oil-of-Olay shots, she says — and she writes the nicest things a person could write, like how she likes my new picture and smiles back at me.

Sometimes weeks stretch on where you don’t hear many nice things from your bosses, from the people around you and from the uber-intense critic inside your own head. And that’s normal, I understand. But I like carrying my little not-normal letter around with me, because it’s just-because nice, a little surprise that keeps you going.

So today’s column is going to start with a Gigi-like event — something that looks nice, genuine and like a break from everyday life.

The event is called Elevision, and it happens every Thursday night in the back yard at the Trident, 940 Pearl St.

Elevision is like a little dharma “Daily Show” — it’s a live talk show in which the host interviews two folks the program consider to be living “the mindful life.” The show also features a musical guest.

“The mindful life” qualification comes from the magazine that sponsors the event, Elephant. Its editor, Waylon Lewis, hosts the event and leads the interviews.

“Waylon is kind of crazy, but we also try to go deep with the people and hit what’s important to them,” says event organizer Heather Mueller.

Elevision used to be held privately at Lewis’s house to be taped for the magazine’s Web site, but for the last two weeks it’s been made open to the public, and already has drawn a patio-filling crowd.

It’s easy to understand the interest — this Thursday’s interviewees include John Perkins, author of “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man,” and Andrew Holecek, a Buddhist teacher and writer.

Mueller says the audience usually starts showing up around 7 p.m., with the interviews kicking off at 7:15 p.m., and the whole evening wrapping up at 8 p.m.

“It’s a great event you can go to and chill out before you head out to dinner and drinks,” Mueller says.

For more information, visit the magazine’s Web site, www.elephantjournal.com, and click on the “Elevision” link…

Contact Camera Nightlife Writer Jennie Dorris at [email protected].

Another, via the Daily Camera, in which I’m quoted:

Rethinking meat: Eating humanely raised animals goes more mainstream

By Cindy Sutter Camera Food Editor

Tuesday, September 4, 2007Waylon Lewis became a vegetarian about five years ago. It made the household run a little easier, since his girlfriend didn’t eat meat.

“We were splitting up pots, so I could cook my bacon and sausage,” he says of the time before he made the switch. Lewis, editor of Elephant magazine, admits he had a few periods in his life when his eating habits were less than mindful — chain restaurant pizza and college went together all too well — but he even as a child he was conscious of where his food came from. Growing up in a Buddhist family in Boulder, his mother got eggs from a nearby house on Mapleton that had a chicken coop, for example.

Lewis calls his transition to vegetarianism “seamless.” He has considered becoming a vegan, because he worries about what terms such as “free range” and “cage free” really mean when he’s buying eggs. Or how dairy cattle, even those raised on organic farms, are treated.

The treatment of farm animals is an issue that’s no longer on the fringe. Burger King announced this year that it would begin a transition to cage-free eggs and chicken. Celebrity Chef Wolfgang Puck announced he would serve humanely raised meats and poultry. Several local restaurants such as the Kitchen and Frasca Food and Wine list the farms that produce their pork and eggs, giving customers the chance to check out the farms on their individual Web sites. Earlier this month at Frasca, Chef Lachlan Mackinnon-Patterson served meat from a calf raised by his wife’s parents on their ranch in Oklahoma.

Options for home cooks have also expanded here with the availability of grass-fed beef, and Colorado-raised pork and chickens at the Boulder County Farmers’ Market and Longmont Farmers’ Market, as well as meats labeled “Certified Humane Raised and Handled” at natural foods stores, mainstream grocers and even warehouse clubs.

Ethical questions

These converging trends have led to what some see as a third way in the once sharp divide between meat eaters and vegetarians: eating animals that have lived a good life up until slaughter on a farm that uses sustainable practices. It’s an approach popularized by Michael Pollan in the widely read “The Omnivore’s Dilemma.” No less a culinary personage than Mollie Katzen, author of the iconic “Moosewood” cookbook, which helped usher in accessible vegetarianism when it was first published in 1977, says she now sometimes eats sustainably raised meat, although she still writes vegetarian cookbooks and respects vegetarians.

It’s a path many vegetarians would still find abhorrent, since even a content farm animal must still be killed to put meat on the table. Lewis, for example, says he doesn’t plan to eat meat again. But for those who do eat meat, the opportunity to be aware of the way in which their food was once treated offers a way out of the don’t ask, don’t tell approach to consuming an animal.

Humane standards

It was this different way of eating that was favored by Adele Douglass, when she founded Humane Farm Animal Care in Virginia. The organization inspects farms and lists them as “Certified Humane Raised and Handled,” a term which the group trademarked, if the farming practices meet the group’s criteria, which are based on input from animal behaviorists and scientific studies.

Douglass explains it like this:

“I would like to see that the animals are allowed to express normal behaviors like walking, turning around, flapping wings — that’s what birds do — rooting around in the ground — that’s what pigs do,” she says. “I started this group, because I’m not a vegetarian. A lot of people like meat, but they don’t like to think their animals are tortured for the short time they’re alive.”

The number of animals covered by the program has grown from 143,000 in 2003 when the group started with five farms to about 18 million animals today.

But what does humane treatment mean?

For farms receiving certification from Douglass’ group, the criteria are very specific as outlined on the group’s Web site, www.certifiedhumane.com. Only one farm in Colorado, Denver-based Maverick Ranch Natural Meats has received certification. Mark Menagh, manager of the Boulder County Farmers’ Market, says many smaller farms have not sought humane certification, because their customers haven’t demanded it. He says the personal relationship that market buyers have with farmers makes certification less necessary.

“A consumer can go and look a farmer in the eye and ask how (the animal) is raised,” he says. “When (farmers) sell consumer packaged goods … once or twice removed from the farmer, that’s when you need labeling, to make consumers know that it’s been handled humanely when they go in grocery store.”

For those negotiating the grocery aisles, terminology can be confusing.

Organic doesn’t necessarily mean humane, for example, although animals are treated considerably better than those raised on industrial farms. Regulations require that the animals not be confined and that they are able to move around, for example. Some groups have claimed, however, that regulations that require “access to the outdoors” for example, have been interpreted by some large operations in ways that may not mean that animals actually use pasture land.

Likewise, humane doesn’t mean organic, although the standards require that animals not be treated with hormones or sub-therapeutic antibiotics or fed food made from mammals.

The terms “cage free” and “free range” are somewhat analogous to the description “natural.” Although, people assume they know what the terms mean, they are not strictly regulated.

Cage-free chickens, for example, are often raised in barns, never living outdoors. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says free-range chickens must have more space to move than factory-raised poultry and “access to the outdoors.” Critics charge that some companies interpret that to mean there has to be a door on the chicken coop.

Even chickens that has been certified humane by Douglass’ group, have their beaks trimmed before they are 10 days old, which Douglass’ says research shows does not cause chronic pain like the debeaking practiced in industrial operations. The beak trimming prevents the chickens from injuring each other.

For consumers looking to transition to humanely raised animals, Douglass says it’s best to start with chicken, including eggs, and pork, since industrial farming practices have the greatest impact on those species. Both chickens and pigs are closely confined in industrial operations, chickens with as little space as an 11 by 8½ piece of paper. Pigs are often raised in crates, where they cannot turn around or walk. Cattle still live a good part of their lives on pasture land, although feed lots can be inhumane.

Knowing your farmer

At Frasca, the specially raised calf was served during one of the restaurant’s Monday night tasting dinners, where it was offered as the non-vegetarian option in the prix fixe dinner. Mackinnon-Patterson called the meat veal, although the cow’s life in no way resembled the factory conditions that led to a huge drop in U.S. veal consumption, after it was revealed that industrially raised veal spent their entire lives in confining crates being fed milk or formula.

Mackinnon-Patterson’s inlaws, David and Susie Koontz, came to Boulder for the serving of their animal. They plan to market their calves as pasture-fed veal. The animals stay with their mothers, nursing and also grazing occasionally if they’re interested.

“This calf never had a bad day,” David Koontz says.

Mackinnon-Patterson also made a commitment to use the whole animal, in a nod to sustainability.

“It takes a degree of creativity,” Mackinnon-Patterson said as he sweated shallots and garlic and ground some of the meat to be used in a bolognese sauce. Other cuts were braised and served with a vinaigrette. A light stew with prosciutto added was also on the menu.

Staff passed out a flier explaining the meat’s provenance.

“Everyone’s into a good story, and it’s a new trend in restaurants,” Mackinnon-Patterson says of explaining food’s origins to patrons. “Chefs could make a huge difference.”

While Lewis will not be eating a calf or any other meat, he says the growing awareness of consumers can eventually make a big difference in how animals are treated and lead to a regulatory tightening of terms such as free range.

“The good news is that consumers are driving the market. Free range hardly existed five or 10 years ago,” he says. “Whether the promises are being fulfilled or not, people have to keep pressing for that to be realized.”

Contact Camera Staff Writer Cindy Sutter at 303-473-1335 or[email protected].cattle, even those raised on organic farms, are treated.