This is the second in a series of excerpts from From the Gita to the Grail: Exploring Yoga Stories and Western Myths by Bernie Clark. The previous excerpt is here.

Are we one or are we two?

Are we divine or merely divinely created? Are we simply in service to a higher power; or do we have a role to play beyond one of servitude?

Is the universe screwed up or just fine; and if it is all cock-eyed, were we the ones that created the problem? How are we to understand ourselves with respect to the universe itself?

The cosmological function of myths, the first of the four main functions that we will explore, shows us how to come into accord with the universe that we find ourselves in. The symbols found in the myths lay out a map, which if we follow will make our journey easier. These symbols are not meant to be historical facts, but they are powerful nonetheless.

According to Joseph Campbell, the proper way to understand a myth is metaphorically. The stories are filled with symbols that speak to us below the conscious level. In order to decide whether the symbol is appropriate today, given our current life situation, if we are to understand the symbols consciously, we need to shine a light into this darkness.

Once we understand the symbol, we may find that it still works or we may find that we would be better off finding a new myth to guide our unconscious reactions to life.

Joseph Campbell was raised an Irish Catholic in White Plains, New York. He knew the symbols of the Catholic Church very well. Like most Catholics his early images of the Virgin Mary were based on the belief that Mary’s virginity was a historical fact: he later learned that this is the wrong way to approach a powerful symbol.

If you read the mythic images as facts, as one might find in the daily newspapers, they lose their real power. For example, if you are told that two thousand years ago, in a small town in the Middle East, a young virgin gave birth to the Son of God, you might think “that is interesting,” but it would not move you to awe and wonder.

However, if you are told that you have God within you and that you will manifest God without any help from anyone else, then the story has a very different effect. If you read the myth as a message to and about you, then the imagery becomes powerful. The 17th century German mystic, Angelus Silesius [1624 – 1677] said: “Of what use Gabriel’s ‘Ave Marie,’ unless he can give the same message to me?”

This is the magic of the myth: it is a personal power because it touches that source of energy deep within you. There is no need to take the stories literally: if you do that, you lose their power.

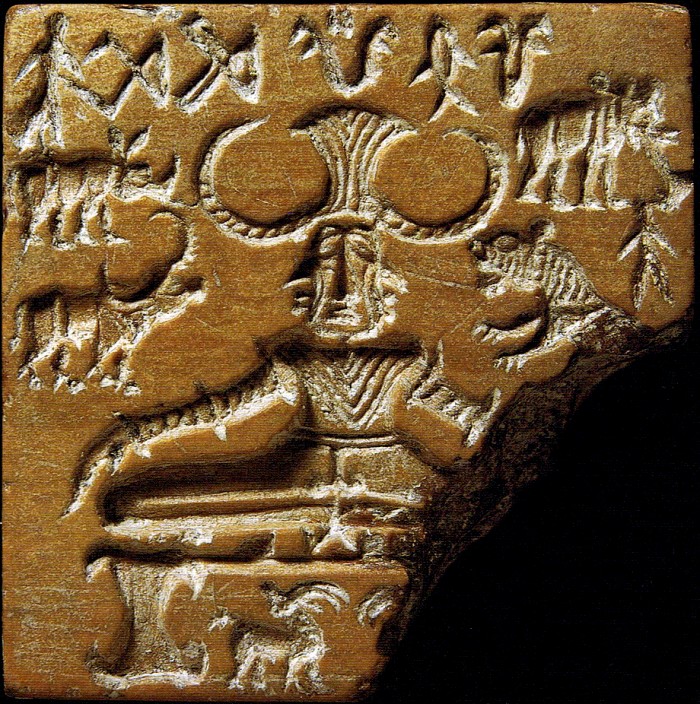

The seal shown above is from the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro, a major city of the Harappan Civilization, also known as the Indus Valley civilization, located in what is now Pakistan. It shows Shiva sitting in meditation. These seals were used in business, to seal cargo before it was shipped abroad. The seals display a form of writing, as shown along the top, but we have no idea what the glyphs mean. There are many symbolic aspects to this little picture, but for now—notice what this early, three-faced Shiva is wearing on his head.

What is that?

Horns! Now, why wear horns on your head? The crown worn by kings and gods are symbolic of the heavens. What is there up in heaven that looks like these horns? The answer is the moon: more specifically the horns of the moon as it initially climbs out of darkness and, again, just before plunging back into it.

The moon is the symbol of the cycles of life. The moon is born out of the sun. Over the 29.5 days of its cycle, it waxes, grows strong and then at the middle of its life, at the peak of its brightness, darkness reappears and the moon wanes; the darkness now expands until the moon dies once more, returning back into the sun. Everywhere one looks, one can find this same pattern unfolding: birth, maturation, duration, decay and death – this is one of the inexorable facts of life.

The moon can also be seen as a cup that fills with life and empties again.

The light of the moon is ambrosia, the nectar of the gods of Greece. In India the liquid of immortality is called amrta.

Mrta in Sanskrit means death and it is connected with our European word mortal and the Spanish muerte. If we put the letter “a” in front of this word, like in English, it means not, so a-mrta means no-death, thus immortality. As the dark new moon emerges from the sun, it fills day-by-day with this amrta, the ambrosia of life. Once it is full, it starts to send the nectar down to earth as dew. In India the hot sun desiccates life; the moon at night replenishes it through the cooling dew.

Thus, the moon empties so we may live.

In the practice of yoga, the symbology of the moon’s liquor of immortality is mirrored physiologically within us. There is a moon center within our brains, the chandra center, which drips amrta.

These drops of immortality fall into the stomach, the home of surya, the sun, where the god of fire, Agni consumes it, just as the moon dies into the sun and is consumed each month. If we want to prolong life, we must stop the loss of amrta, so yogis turn themselves upside down. Inversions in Hatha Yoga are one means to stop this constant leaking away of life.

Headstands and shoulder stands are the royal asanas, the king and queen of postures, which help the yogi live longer. This harkens back to another metaphor: the moon’s life giving energy stored in the brain is soul-food, semen. It too must be conserved, and in many yogic mythologies, it is conserved through sexual abstinence, celibacy.

Do not take any of this literally, of course. The ancients didn’t believe that there was an actual moon in our brains dripping ambrosia that would allow us to live forever. The chandra and surya centers in our body were metaphors that worked: as long as we acted “as if” there were these centers; that the nectar of immortality was being consumed inside of us; and as long as we acted “as if” turning this flow around would prolong our lives, then we could reap benefits.

Acting “as if” a myth is true is the best way to reap the metaphorical benefits from the story.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Renée Picard

Images: courtesy of the author; elephant archives

Read 0 comments and reply