It is easy to retreat into the comfort of simplified worldviews when confronted by complex and seemingly unsolvable problems.

These painfully simple conclusions serve to insulate us from guilt and responsibility by completely justifying the actions of the side with which we are identified and wholly condemning the opposition.

In the case of racism, the line of demarcation is skin color. So, in response to accusations of discrimination and inequality, the white majority hides behind a willful denial of the obvious, stating that minorities have access to all of the same benefits and are protected equally under the law.

Therefore, all of their problems are of their own making.

While the minority and many of their liberal proponents paint a picture of ubiquitous socio-economic oppression often labeled the theory of white privilege.

Most people are not interested in the complex. They prefer the comfort of their simplified bubble, because it does not necessitate personal change.

This is the easier, softer way.

But “character cannot be developed in ease and quiet,” as Helen Keller once said.

Change is initiated by our willingness to confront the facts and accept the implications of these facts, regardless of whether we stand to profit from such a confrontation or not.

In fact, effective change can only be accomplished when we are willing to face our own shortcomings—both as individuals and as a society—with humility and resolve, because we are the only ones who can effect change within ourselves.

But in order for this to happen we have to step out of our bubble.

So, who is right? Is America a bastion of social equality and economics justice? Or is the theory of white privilege an accurate portrayal of the social, economic, and political circumstances that burden minorities in the United States, particularly African-Americans?

Many in the white community have reacted with outrage at the notion that police officers target African-American men. Is their outrage justified? The Center for Disease Control reports that 2,151 whites were shot and killed by police officers in the United States between the years of 1999 and 2011.

In contrast, 1,130 African-Americans were shot and killed during the same time span.

So, the police have actually shot and killed more white people than black. However, the picture begins to shift when you consider that African-Americans make up only 14 percent (45 million) of the total American population, compared to the 61 percent white majority.

Therefore, an African-American is three times more likely to be shot, subjected to force, or threatened by a police officer, than a white American.

While this may be true, some have argued that this is due to their behavior, not their skin color. The CDC reports that the number one cause of death for black males between the ages of fifteen and thirty-four is homicide. According to the Department of Justice, African-American males are six times more likely to die of homicide than white males. Without slipping into the simplified notion that all white cops are racists, this serves to explain why some police officers are more cautious of approaching a black man than a white man.

Does this mean that blacks are inherently more violent than whites? Absolutely not.

The Department of Justice also reported that two-thirds (65.6%) of all drug-related homicides were committed by black offenders. The homicide rate amongst black males is directly related to drug culture. Are African-Americans at an increased risk for substance abuse?

No.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration found that 8.9 percent of African-Americans twelve years of age and older are considered substance abusers or substance dependents, compared to 8.7 percent of the white population. African-Americans are no more susceptible to substance abuse than whites, however they account for two-thirds of all drug-related homicides.

The African-American population is gripped by the drug culture and plagued by its associated violence—not because they are at an increased risk of addiction or inherently more violent, but because they are gripped by poverty.

The increased rate of violence amongst African-Americans is linked to drug trafficking—not drug use or a violent predisposition—which is necessitated by poverty.

Some may respond, “Well get a job…Don’t break the law!” Is this a fair response? Is it as easy for an African-American to get a job as it is for a white person, or is such a rebuttal symptomatic of white America’s degree of disassociation from the African-American plight?

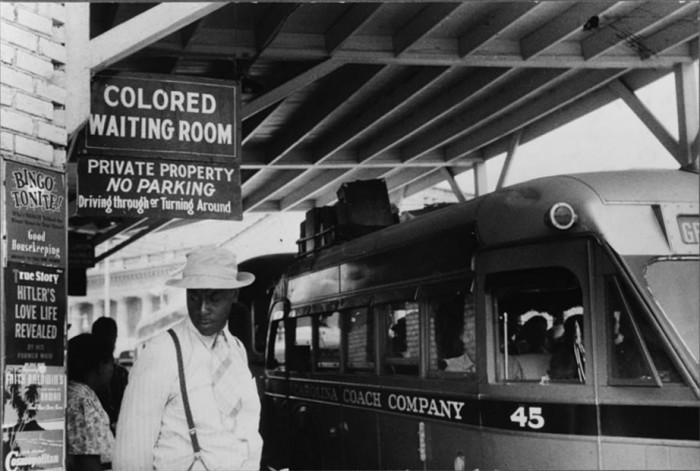

Since Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st 1863, much has changed for the African-American population: They have obtained individual freedom, the right to own property, vote, and have gained access to many of the day-to-day conveniences white people take for granted, such as lodging, public restrooms and water-fountains, and restaurants.

However, one thing they have not gained access to is employment. According to an article published in August of 2013 by the Pew Research Center, “In 1954, the earliest year for which the Bureau of Labor Statistics has consistent unemployment data by race, the white rate averaged 5 percent and the black rate averaged 9.9 percent. Last month, the jobless rate among whites was 6.6 percent; among blacks, 12.6 percent.

Over that time, the unemployment rate for blacks has averaged about 2.2 times that for whites.”

In the South these numbers are even more discouraging. Take for example Ferguson, MO where, according to Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly, “The black unemployment rate is three times the white unemployment rate; Black men between the ages of sixteen and twenty four have an almost 50 percent unemployment rate, for whites it is 16 percent.

She continued, “In the United States a black child is almost four times as likely to live in a poor neighborhood as a white child; 20 percent of white kids are in single parent homes, while 52 percent of black kids are.”

One could argue—as Bill O’Reilly did when Megyn Kelly presented him with these numbers—that families and culture drive these statistics, not racism.

Perhaps families do play a role—and not an inconsequential role either—in the problems that plague blacks in the United States. But where do these family problems come from? Do African-Americans simply not value family or are there other explanations?

“Black men are more than six times as likely as white men to be incarcerated in federal and state prisons, and local jails,” writes Bruce Drake of the Pew Research Center. African-Americans currently account for 1 million of the 2.3 million people behind bars in the United States. Among regular drug users, African-Americans represent 13 percent of the population, but somehow they represent 56 percent of drug convictions and 74 percent of the people sent to prison for drug possession crimes.

“Black men are more than six times as likely as white men to be incarcerated in federal and state prisons, and local jails,” writes Bruce Drake of the Pew Research Center. African-Americans currently account for 1 million of the 2.3 million people behind bars in the United States. Among regular drug users, African-Americans represent 13 percent of the population, but somehow they represent 56 percent of drug convictions and 74 percent of the people sent to prison for drug possession crimes.

Not only are they more likely to be targeted by police, convicted, and sentenced, on average African-Americans serve nearly as much time in prison for drug offenses (58 months) as white offenders do for violent crimes (61 months), according to the Sentencing Project.

This is in large part due to the alternative sentencing offered to offenders with money, such as diversion programs and fines—not to mention the magic worked by many high priced attorneys capable of getting reduced sentencing for third, fourth, and fifth offences.

However, this is a privilege afforded to individuals with money, a group which includes few African-Americans due to the before mentioned unemployment rates.

Another contributing factor in the disparaging incarceration rates is mandatory minimums, which disproportionately affect blacks leading to many fatherless households.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 created a 100 to 1 sentencing disparity for crack/cocaine—traditionally a drug found in black communities—vs. powder cocaine—a more expensive version of the same drug, meaning it was more readily available to people of means, i.e. white people.

Therefore, five grams of crack warranted five years in prison, while it would take 500 grams of power cocaine to illicit the same punishment. In 2010, Barack Obama reduced this disparity down to 18-to-1 and removed the mandatory minimum of five years for simple possession of crack/cocaine. This is due in large part to such sentencing disparities one out of every six black men have been incarcerated at some point in their life.

This, coupled with the fact that black men serve 20 percent longer prison sentences than white men for similar crimes (U.S. Sentencing Commission), has created an epidemic of fatherless homes in the black community. Furthermore, the affects of imprisonment on the individual are not inconsequential.

These prolonged sentences create an institutionalized mind or a mind that only knows how to function within an institution, and as a result black inmates are 43.6 percent more likely to reoffend. Consequently, one hundred and sixty years after the Emancipation Proclamation, there are more African-Americans on probation, parole, or in prison than there were slaves in 1850.

The other causal force cited by Bill O’Reilly was culture. The topic of culture is extremely complex. It is the collective unconscious of a whole people, and when we open this repository we will find all sorts of stuff, good and bad alike. But it is important to remember that culture does not develop in a vacuum, and much of African-American culture developed in the fields of the plantation. A lot of what developed was beautiful: spirituality, music, art, and dance.

Some of it was debilitating and those debilitating forces still linger today. Over the course of centuries, African-American families were split up at the slave market. Husbands separated from their wives, sons from their fathers, and daughters from their mothers. The slave trade destroyed the family unit. Furthermore, African-Americans were, for centuries, systematically taught to devalue education.

It was by the sweat of their brow that they survived on the plantation, not their intellect. They were severely punished for learning to read, and now they are in a position where education is their ticket to freedom.

The White Privilege theory states that white people experience societal benefits beyond what is commonly experienced by non-white people in the same social, political, or economic circumstances. Critics of this theory argue that American society extends the same benefits to all people regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity and that the failure of an individual to prosper within the social structure represents an inherent shortcoming in the individual or group of individuals, not the social structure itself.

As suitable as this opinion might be to the conscience of white America, it simply does not hold up when critically analyzed. Social, political, and economic structures are not self-existing, natural structures. They are man-made systems and in predominately white societies these systems were engineered by white men. In the United States, where there is a long legacy of black oppression, it is not hard to imagine that the same forces that created the institution of slavery or Jim Crow continues to affect the laws and practices that shape the social, political, and economic circumstances of African-Americans, establishing a tone of white privilege.

Someone recently told me a story that perfectly illustrates this point.

They were sitting around passing time with their co-workers, including their supervisor. Everyone was laughing and cutting up, and then the receptionist notified the supervisor that a man had come in to apply for the open position.

The supervisor was immediately disappointed because the interview was going to take him away from the fun, but then he looked up and saw the applicant. He was black. The supervisor told his friends, “This won’t take long. I’ll be right back.” Just as we all do on the morning of an interview, this man got up and prepared himself. He took a shower, ate breakfast, and put on a nice set of clothes. He sat out in the sweltering heat of summer at an uncovered bus stop only to be denied a fair chance at the job because of his skin color.

This is common practice. I can only imagine how it would feel to be outright dismissed without consideration by employer after employer. Literally, that is all I can do is imagine, because there is not a conceivable scenario where I would be denied a job due to my skin color in the U.S. For me, this scenario is and always will be purely hypothetical, whereas for many people of color it is the day-to-day reality, and it is this drastic polarity that accounts for what is called white privilege.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Read 8 comments and reply