Know thyself.

Through yoga we aim to learn our true nature, and mediation is one part of this journey.

I’ve been practicing meditation as long as I’ve been practicing yoga asana. When I first started to dabble in yoga, I was lucky enough to have teachers who would design their class so that a good portion was left for meditation and pranayama.

I wish I could say that I meditate religiously every day, 30-plus minutes a day—but I don’t. Typically I’ll squeeze in three (or fewer) ten-minute practices a week. And by that I mean actually sitting still doing the whole business: straight spine, cross-legged, eyes closed and the like.

Even less than 30 minutes of practice a week is enough for me to see some benefits.

It’s calming and I’m giving myself space to let all other commitments go. I can refocus on the thoughts that are racing around in my head about things I need to do when I’m finished—they’re not going anywhere.

I’m unquestionably more focused when I’ve been practicing. We use strength resistance to train our muscles, cardio to increase the capacity of our lungs and hearts, meditation is training for the mind.

I also use meditation as a tool to investigate the intimate workings of the mind. This has led to a shift in what I consider to be me. By which I mean the real core essence of myself. The mind is continuously sensing the flux of the outside and internal world, modifying our working understanding of it all, and governing our ever-changing feelings and behaviour.

The historian Drew Faust said it well:

“We create ourselves out of the stories we tell about our lives, stories that impose purpose and meaning on experiences that often seem random and discontinuous. As we scrutinize our past in the effort to explain ourselves to ourselves, we discover, or invent, consistent motivations, characteristic patterns, fundamental values, a sense of self. Fashioned out of our memories, our stories become our identities.”

Through introspection I try to pick apart my own mind—how it senses the world and the underlying experiences and motivations that influence my perceptions and actions.

It left me thinking—is this all there was to me? Was I simply a lifetime sum of experiencing streams of thoughts and sensations from my internal and external world? Or, even more simplistically, a combination of what I’m feeling in the present moment? Either way there is constant change.

Thanks to meditation, this all started to change.

There are a number of different meditation styles within the yogic tradition; open monitoring is one. It’s a style where we become less identified with the fluctuations of the mind. Instead, we practice cultivating awareness of thoughts, feelings and sensory perceptions. We remain attentive but with a sense of dispassion; free of judgment or selective focus. This is in contrast to focused attention styles of meditation where the focus of meditation is an object, most commonly the breath.

For me these meditation styles aren’t mutually exclusive. My practice starts by placing focus on the breath. The shift from my typical mode of thinking to a state of observation is too great a leap; I need something to bridge the transition. Focusing on the breath allows me to step back from the flow of mental “chatter” and fluctuating sensory pre-occupations, and instead use one object of attention to anchor into the present moment. From there my focus can slowly widen and thoughts and sensations come and go while I practice remaining uninvolved and simply aware.

During open monitoring we take the role of the observer, watching the fluctuations of mind. This is reminiscent of the Homunculus argument:

The Homunculus (Latin for small man) is an observer in our heads that watches our cognitive processes. This likely seems an odd proposition—a man inside our heads. However, it’s a metaphor for an intelligent agent that observes the processes of the mind.

The Homunculus argument goes back to Descartes, who suggested that the Homunculus was the soul, and that the soul was necessary for consciousness. He even suggested that it was located within the pineal gland. Because of its privileged position in the middle of the brain it could observe the ongoing cognitive processes.

In the Yoga Sutras, a dualistic perspective similar to the homunculus is suggested. Our consciousness is distinct from the mind, body, and environment. Specifically, the distinction is between consciousness and what can be perceived.

The problem with the Homunculus is that he, as an intelligent agent, would also require his own consciousness, his own Homunculus. Within the Homunculus would be another, and within that another—with infinite regression of Homunculi.

The Homunculus argument is typically considered a fallacy. For example, the contemporary philosopher Daniel Dennett is well known for denouncing the theory. In his work he calls it the Cartesian theatre model of consciousness, and argues against an “end point” of cognitive processing where the mind meets awareness.

Within the Yoga Sutras it appears that Patanjali also suggested that consciousness was more than just the observer of the mind. Instead, it controls and illuminates its processes (sutras 4.18 & 4.19). At times, we can become absorbed within the fluctuating thoughts and feelings of the mind. Open monitoring meditation is a means by which we can step back from this absorption and begin to abide in our awareness.

Here we find the Self. The Self is consciousness. It isn’t material matter, it is devoid of content. It can’t be seen because it is the seer. It never changes because the act of being conscious does not change. Instead, it’s the objects of our awareness that fluctuate and imbue our existence with different experiences.

When we are not preoccupied with this ever-changing nature of experience and instead enter into a state of absolute awareness, one can find Asamprajnata-Samadhi. Defined as the highest state of yoga, this is the ultimate state of awareness in which nothing can be discerned but the pure self.

Have I found Asamprajnata-Samadhi? Not yet, but I’m learning to experience my mind in a newfound way. Its ever-changing thoughts, feelings, and memories are not so intertwined with my sense of self.

It’s an interesting switch in perception because I’ve often associated my sense of self with the fluctuations of the mind. For example, there have been times in my life when I’ve felt angry, frustrated, hurt, or shy. Sometimes I’ve started to believe they’re characteristic of me and I’ve identified with them. But none of these feeling are me, and none of the thoughts that gave rise to these feeling are me. These functions of the mind are not the core essence of my self. Still, I can experience them. Just like I can experience the taste of coffee or the chill of a winter wind; but there is no need to identify with any feeling or thought because these are just fleeting sensations.

This has been an amazing shift in perception that I’ve taken into my day-to-day life. I’ve found that when I’m not caught up in my thoughts and emotions, I have more space to be present and attentive in my day-to-day tasks and less emotionally reactive in my relationships. I’m definitely not an enlightened human free of periodic zone outs or regrettable emotional reactions but I’ve seen improvements and I feel happier.

This in itself keeps me practicing.

One day I might experience the essence of myself that doesn’t change in this constant flux of this human experience, that which we call pure consciousness. But even if I never do, this has been a worthwhile and surprising journey of self-discovery.

I really do recommend practicing meditation. It doesn’t take as much commitment as you may initially think and what do you have to lose?

Well, maybe just your current sense of self.

~

Author: Kathie Overeem

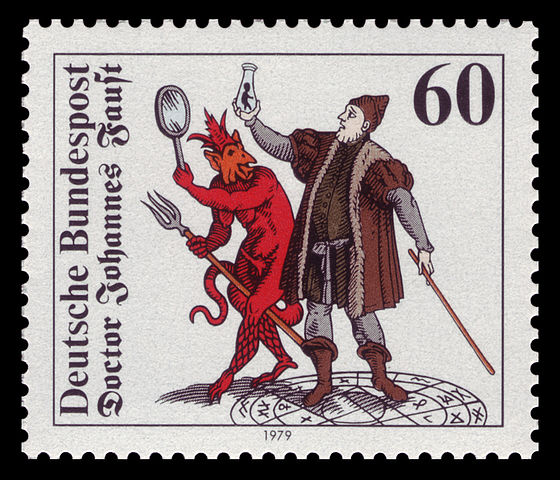

Image: Public domain // Wikimedia Commons

Editors: Sarah Kolkka; Emily Bartran

Read 6 comments and reply