Most of us who have studied the Buddha’s life are aware that he ate once a day at noon and consumed only water after that time.

Close disciples who followed him through his decades long teaching career also engaged in this practice. Many may not be aware, however, of the intricacies of this practice, and some of the levels of keeping it, so let’s take a journey and explore them with the aim that we might glean an insight or two into improving our own eating habits.

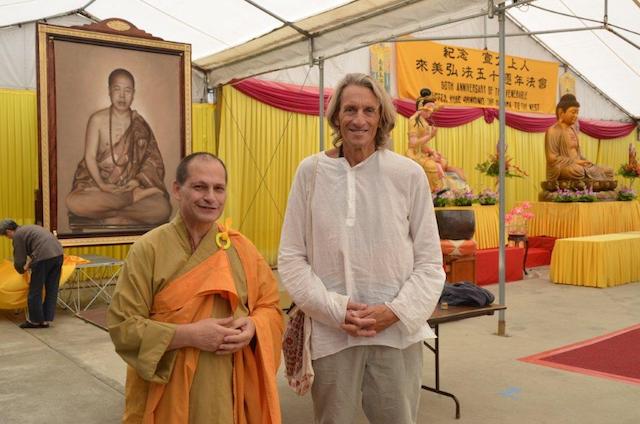

I lived with the Manchurian Master Hsuan Hua for a decade at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, in Northern California. He was a vegetarian, as were all the monks and nuns, as well as his lay followers. Although the Master ate once a day, he did not impose his personal preference on anyone—yet we could not resist following his example.

The Buddha did not eat once a day as an act of austerity as one may think, but rather for health benefits and its practical advantages. Buddhist masters who engage in this practice emphasize the health benefits by pointing out that a single meal means the body only needs to digest food once a day and, therefore, expends far less energy than a typical three meal a day diet. Moreover, less time is spent preparing, consuming, and cleaning up afterward. When the body is given less food, necessity assures full use of the nutrients it receives.

When I entered the monastery, I weighed 200 pounds and ate three times a day. I was strong, young, and energetic. After a few months of eating once a day, I clearly saw its advantages. I was eating less, but weighed the same, and my energy levels increased dramatically. Not surprisingly, during digestion, energy typically dips and, if you eat once, it dips two-thirds less than if you ate three times. Moreover, I was not unique; over the years I saw many newcomers enter our monastery who, like myself, lost little or no weight and felt a boost in energy.

In addition to eating once a day, there were other disciplines regarding the single meal. One of the most common during the Buddha’s time, and at our monastery, as well, was to eat a single bowl of food. Interestingly, the bowl can be any size. Therefore, we sometimes see monks with huge bowls.

I did this practice for most of my monk career, using bowls of diverse sizes, from a huge stainless-steel pot to smaller vessels. My most austere discipline in this regard was eating only a coconut shell bowl of food a day. A fellow monk and I kept this vow for two years, and I broke more shells by trying to cram food in them than I can count. But, I must say, this practice taught me a lot about nutrition—far more than my huge bowls could. I really had to think what I put in that bowl, or long before the next meal, I would be hungry and drained.

My fellow monk, Dharma Master Heng Shun and I occasionally traded notes on what were the best foods to assure we would endure at least a year on our single coconut bowl a day diet. We were learning a lot throughout the two-year period we kept the vow, but 90 percent came in the first month.

Our monastery offered buffet style lunches prepared by the Master’s devotees each day. They would generally arrive in the early morning and prepare food for the noon meal. What they prepared was unpredictable, but there were generally staples like bread, honey, and peanut butter always available. The monastery was vegetarian, although now mostly vegan.

We grouped our foods according to those that would provide lasting energy, those that cleansed and purified, and those that provided sugar for digestion. A typical bowl would be layered: nuts, peanut butter, dry fruits from the bottom to the first-third or half, green vegetables almost to the top, and sliced fruit at the top. We could not consider taste.

The monks and nuns not restricted by bowl size, but who ate once a day, often ate in a similar fashion considering what is going to cleanse on the one hand, and what is going to stay with them on the other. Even though the others didn’t have the bowl size restriction we did, the reality is, our stomach is our natural bowl and you can only put so much in it.

All the monks and nuns at our monastery learned to eat well by necessity. Typically, lots of greens, far more than you would see in a restaurant serving, at least three or four times as much. Also there was always nuts, dried fruit, or peanut butter, and lots of it, the exception was if you opted for brown rice and beans, if available.

The Chinese use a lot of tofu and faux fish and meat made with soy, flour, and gluten—very high in protein—and this was often available for us to eat. When it was, it would generally knock peanut butter off the menu. This was the salvation for most of us. Everyone ate some grain and greens with meals, but not always fruit because it fills the tummy.

Remarkably, everyone was healthy except for those ruled by taste, who learned the hard way, often by getting sick, malnourished, and developing nervous disorders. During my 10 years as a monk, I never missed a ceremony because I never was sick a single day, not even a cold! Many others in our monastery observed that they were remarkably immune to downtime and attributed that to a single meal with attention to what assures good nutrition rather than taste.

Another practice spoken of in Buddhist texts is eating in one sitting. The hidden benefits of this are not so obvious. When you take this vow, you can take several bowls of whatever you want, or a single bowl, but once you have sat down, you cannot get up again to get more food, or have someone bring you something. This means that if you forgot something you really wanted, tough luck. It teaches us to be mindful while taking food and restrained afterwards. It also helps us gauge how much we need, because what is taken must be eaten. Monks eating once a day generally take too much and have sore tummies during the first few years of monastic life.

Taking food in silence is also a necessity for monks. When you eat, your mouth is used for that purpose, and talking is both a distraction and impractical. Moreover, food that is fully appreciated is digested better. Monks don’t talk while they eat, but they may listen to teachings.

After my 10-year stint as a monk, I continued to eat once a day for about a decade. As a married layperson, I had a family that made it impractical at times, but I enjoyed the practice and continued. I gradually—to once again enjoy an extra couple of meals—went back to three meals a day.

One benefit that has carried over from my eating a single meal is that I don’t snack. If I am not seated to eat a meal, I don’t eat anything. Eating once taught me something about digestion, and that is that anything you put in your stomach, even a handful of dates or nuts, will start the entire process going, and that consumes energy that could just well have been saved for mealtime. Moreover, not snacking disciplines the mind, and this restraint has benefits that carry over into many things I do, including meditation.

The Buddha lived over a decade longer than the life expectancy of his time, around 80 years, some say. Moreover, he was healthy and on his feet walking the dusty plains of Bihar for 50 years, even toward the end of his life. He was teaching almost daily and moving from place to place conducting his sermons. He ate a single bowl of food every day, and begged from house to house, accepting whatever offerings were put in his bowl. His long, healthy, and active life is an inspiration to let the body take care of itself with simple, nourishing foods.

~

~

~

Author: Richard Josephson

Image: Author’s Own

Editor: Travis May

Copy Editor: Catherine Monkman

Social Editor: Nicole Cameron

Read 1 comment and reply