Like most global citizens of the 21st century, I didn’t just wake up in an ashram.

I was something like Elizabeth Gilbert in “Eat, Pray, Love”—except that I was eight years old, and my mother was a student of Indian philosophy.

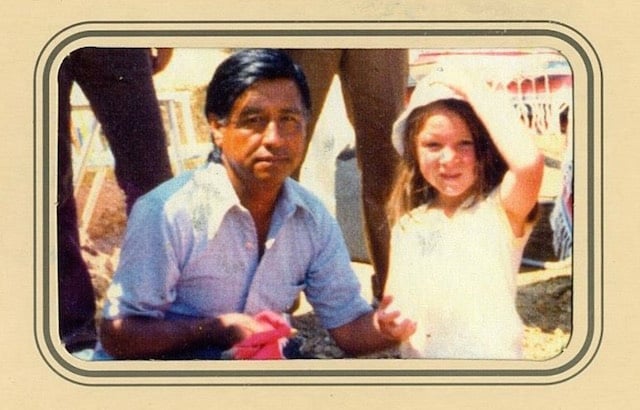

Both of my parents were seekers of the 60s: my father was a progressive Russian/Jewish activist from Peru and my mother was an Iowa girl, imbued with Catholic values with a flair for the bohemian lifestyle. While many kids were watching cartoons, I was marching with the civil rights activist Cesar Chavez and going to nude beaches with my father, while my mother went to Switzerland to learn about meditation from a great sage whom she adoringly called her “guru.”

I was five when it was clear to me that their approach for saving the world had internal conflict. “Si, se puede” (yes, you can) was marked in my young psyche as the catch phrase for social change, but the Sanskrit sloka or prayer, “Vasudaiva Kutumbakam” (Sanskrit: वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम् meaning, “The world is my family”) was my ethos. I understood this to be the pinnacle of perfection.

The aspirations of my education were lofty. I would ponder broad philosophical concepts pertaining to dharma (duty) and karma (action) while reading The Bhagavad Gita—one of the pillars of our Vedic studies. “Nistraiguno Bhavarjun” was the advice of Lord Krishna to the young warrior, Arjuna, on the battlefield thousands of years ago. The meaning was to transcend, and from this quiet state of mind, perform action. This is sound advice which all cultures utilize—prayer, intuition, guidance from our elders, all with the intent to ensure efficient results.

At home, my mother was more devote: paintings of the ethereal devotion between Radha and Krishna or Sita and Ram lined our walls; these celestial avatars were all known as the embodiment of the masculine and feminine aspects of creation in pure love.

At school it was more scientific. I saw the path to enlightenment through unified field charts which unfolded sequentially from the gross physical world to the atoms and from there unified field theory, which quite frankly, confused me. Why did I see cutting edge physics within the big bang thought bubbles of my mind? My quietest place had more monkeys than your average, apparently.

I absorbed the knowledge that the DNA of Vedic culture was passed on from father to son, within the highest cast in India. My innocent conclusion was that I was the curdled cream in the chai. At university, my Swedish girlfriend dated the son of a prominent Indian philosopher. I watched their sweet love story: the winter walks and dates at coffee shops. It didn’t end well, for the simple reason that her culture didn’t mix with his. My take-away? I promised myself I would never date an Indian man.

Well, isn’t life a cosmic joke? After spending a year abroad, I stood behind my future husband in line for registration. He was tall, dark, and handsome. My heart began to flutter—what should I say? I asked about his family. “My father is in India,” he said. “Why would your father be in India?” I asked. “Because he’s Indian.” Me: “Ohhhh…”

And so our love affair began, and I sang Carly Simon’s “Clouds in my Coffee” with bravado. This was a simple act of defiance. I was Indian inside, wore saris since I was eight, and dhal was my comfort food. I can do this.

Once we married, I went full in. I was going to be the perfect wife and learn to make the best damn chapatis this side of the Mississippi. We started attending Indian gatherings. In the beginning, the men were on one side and the women were huddled on the other, chatting in Hindi with lukewarm smiles from time to time. I’d awkwardly try to talk to my husband on the men’s side, but quickly realized that I was best off leaning against the window sill and smiling.

Little by little, new Indian friends came in the picture, younger and more progressive. Deep friendships formed and after some years I was even on the email list, consulted for dhal recipes, and my rajma was a local favorite. I had a sense of belonging, a sense of family, and even I was shocked by how white I was.

But as they say, the higher you go the harder you fall. Life has a way of chipping away the whitewashing of any paint which isn’t yours; the layers of conforming, and peeling to bypass conditioning and revel in rawness.

While the desi in me is ingrained in every cell of my being, I increasingly own who I am—a woman who belongs to the world. Perhaps this is why I’m a vehement proponent of respecting each other, regardless of cast or creed, country or religion. We are not celebrated for what we are if we are constantly contrasting with what we are not.

I’m reminded of a scene in “Eat, Pray, Love” where Elizabeth Gilbert’s character is in an ashram in India and she comes across a lady “in silence.” (“Silence” is the practice of not speaking for days at a time to ensure full rest of the nervous system.) Any person who has experienced ashram life will see how often comical that interaction is. As an eight-year-old surrounded by meditating adults, I thought, “Could somebody please just get out of lotus and get me some Skippy!?” And, “If this is enlightenment then, um…no, thanks.”

At a very difficult juncture years later, I was told that I didn’t have enough “karmic credit” to reach my goals. Perhaps this lack of heart among proponents of idealism made me question: “Can knowledge which stays in the books actually translate into a better world?”

I often say there’s a quote to justify anything. You want donuts every morning? You’ll find a quote to make you feel great about that. I sought new inspiration—I wanted to surprise my mental taste buds with something unpredictably delicious.

If the world is indeed my family, I want to travel more, and I want to know every member. I met some brilliant friends of the Muslim faith who shared their interests, writing, photography, and social views—many of whom also practiced yoga and healthy living techniques. Their daily prayers were a means to center themselves regularly throughout the day.

I was touched by the open-mindedness and respect. I visited people in prison, whom life didn’t afford the same comforts, and became aware of the willpower it takes to care; the immense courage it takes to invest in life, health, philosophy, and education when darkness and lack of love surround you.

How different would the world be if we were more courageous in our acts of kindness and inclusion, if we used compassion in practical ways to challenge the norms of society? What would happen if we stopped reading billboards on the highway of life, and read the fine print, or even took a detour?

Perhaps I have heard Kumbaya one too many times, but as an accidental traveler, wouldn’t it be fascinating to visit the unchartered? It could be like a wild family reunion with the uncle from Siberia and the aunty from Uganda.

We could serve donuts because we would then be the master of our own destiny; and as you already know, there’s a quote somewhere about eating donuts every day. With chai, of course.

Author: Caterina Bacal Titus

Image: Author’s Own

Editor: Sara Kärpänen

Copyeditor: Nicole Cameron

Read 15 comments and reply