Spiritual arrogance is not so easy to avoid as one might think.

It is like a cold no one wants to catch, but is almost unavoidable. The same can be said of spiritual arrogance—we may not like it, but if we aren’t careful, it is bound to entangle us.

Practicing the path of dharma is not the same as eating its fruit, but we can easily confuse the two. When we do, that’s spiritual arrogance.

It is a trap anyone can fall into. I certainly did.

I quit surfing to live in India, trading Hawaiian beaches for Calcutta streets. My friends thought I was nuts, maybe so, but I didn’t see surfing as a cure. One day I walked on a Waikiki beach with a “for sale” sign on my board. Within minutes my surfing career was over, and I said adios to my surf buddies.

Of course, I was broke—dedicated surfers generally are—so I had to work. Within two months I had saved $2,000, thanks to a construction job on the Big Island.

It lasted me two years in India and Nepal. I never had more than flip flops, a t-shirt, and a “dhoti, (a light cotton waist wrap about the size of a medium towel, popular in India where weather permitted), which like surf trunks was simple and comfortable.

I kept a small backpack with a few toiletries and didn’t need more until I went north to Nepal, where a warm jacket was also needed.

I travelled around quite easily seeking out yogis and yoginis, despite my tight budget. Bumming around is another surfer quality, for, where there is surf, there often isn’t lodging—you sleep where the waves are.

But now on my spiritual quest, it meant ashram floors, or caves, or sandstone open places, as in South India. It didn’t much matter where I camped, awash as I was in my quest.

I was a surfer seeking gurus, but as being in the presence of gurus and yogis began rubbing off on me, and as the months passed, my identity as a surfer began to fade and I began thinking of myself as one of the many yogis I met.

In a South Indian desert, I lived in a cave for six months, and it was here that circumstances inflated my already deluded self-image. Villagers began walking up to my cave to make offering of flowers and fruit and bow to me. At first, I was smart enough to think their worship misplaced, but it didn’t take long before I began to think I really was a yogi deserving their respect. We often perceive ourselves as we believe others do.

During the months in the cave I recited mantras most of the day. I became, as it were, hypnotized by my own dedicated devotion and the villagers visiting me. It wasn’t until I returned to Calcutta that I was put in my place. I related to my bright Bengali friend, Clifford, the story of the villagers. Clifford snapped, “Oh, South Indians will worship anything!”

Slightly tamed by Clifford’s words, and feeling a bit more like a surfer again, I hopped on a bus for the 48-hour ride to Kathmandu, Nepal. While in Calcutta, some friends of Clifford advised me not to stay in Kathmandu, but instead go to Tengboche, in the Solu Khumbu region, not far from Mt. Everest base camp. There I would find many Tibetan monasteries and yogis they promised.

After the bus ride, I wasn’t six-feet-four any more, and it took a week to unfold myself into climbing condition.

The bus out of Kathmandu takes about eight hours to get to the end of the road and the beginning of the climb, which was no ordinary stairway, just how much so took me all day to figure out. The stones composing the stairs were granite, about six feet long and a foot thick, sometimes two stacked together, sometimes one, with no real evident logic and about two feet deep.

It looked like I could reach the top in about half an hour, but I was wrong, as each “top” was followed by a very brief levelling off before the next set of stairs continued.

The entire day was spent from morning to night getting to the top of the stairs, where I lodged in the first house that invited me in.

After two weeks of walking, I tired and asked the abbot of a trail-side monastery if I could stay a while before moving on. Permission was gladly granted, and I stayed with the lama and his wife in their small but famous “gompa,” sleeping in the center of their shrine room, while they retired to its corner. There I stayed a month, meditating from morning to night, the lama playfully whisking me whenever he dusted his statues.

By month’s end, my surfer identity diminished and I pressed on toward Tengpoche, feeling more like a yogi again. I still had two weeks to go, but never made it.

After a full day of trekking, I asked to spend the night at another monastery. When I arrived toward evening, the area was covered in mist and I had no idea where I was until the next morning when I stepped outside to brush my teeth. There, facing me and not far from where I stood, was a 25,000-foot glacier covered peak, rising vertical.

I said to myself, “no point in moving further,” and asked the abbot if I could stay. He agreed and gave me a small stone hut beside the monastery. It had rice paper windows and a place to burn wood in the middle of the floor. The wind howled through the walls which lacked mortar. It became my home for one year.

I sat meditating in my hut for almost the entire year, hours a day, the notable exception being every evening when I would converse with the abbot in the monastery, or when I gathered wood for the monastery with the mother of one of the abbot’s disciples.

The abbot criticized my meditation, saying I was no better than a hibernating bear, adopting the position but having no illumination. Nonetheless, I was growing more enthusiastic day by day, and despite the abbot’s warnings, I believed I was quite the yogi. Although the abbot tried to impress upon me the importance of having a spiritual guide and study, I was content doing it my way.

Despite my stubbornness, the lama and I were destined to become close friends. During that year I met many hermits, yogis, and high masters who visited the abbot. But, instead of becoming humbler, I became full of myself, imagining I was equal to the company I was keeping, not realizing that this surfer boy was but a novelty to them.

I was destined to be humbled, however, from eight words uttered by a carpenter whom I was to meet shortly after saying goodbye to Asia and hello to San Francisco.

I arrived in San Francisco, topknot and all, seeking a dharma center to continue where I left off in Asia. Having completed my two-year stint, I was very pleased with myself. I sought out a monastery to continue my practice and settled on Gold Mountain Monastery in the heart of the Mission District.

A week after I arrived my self-image was shattered unexpectedly.

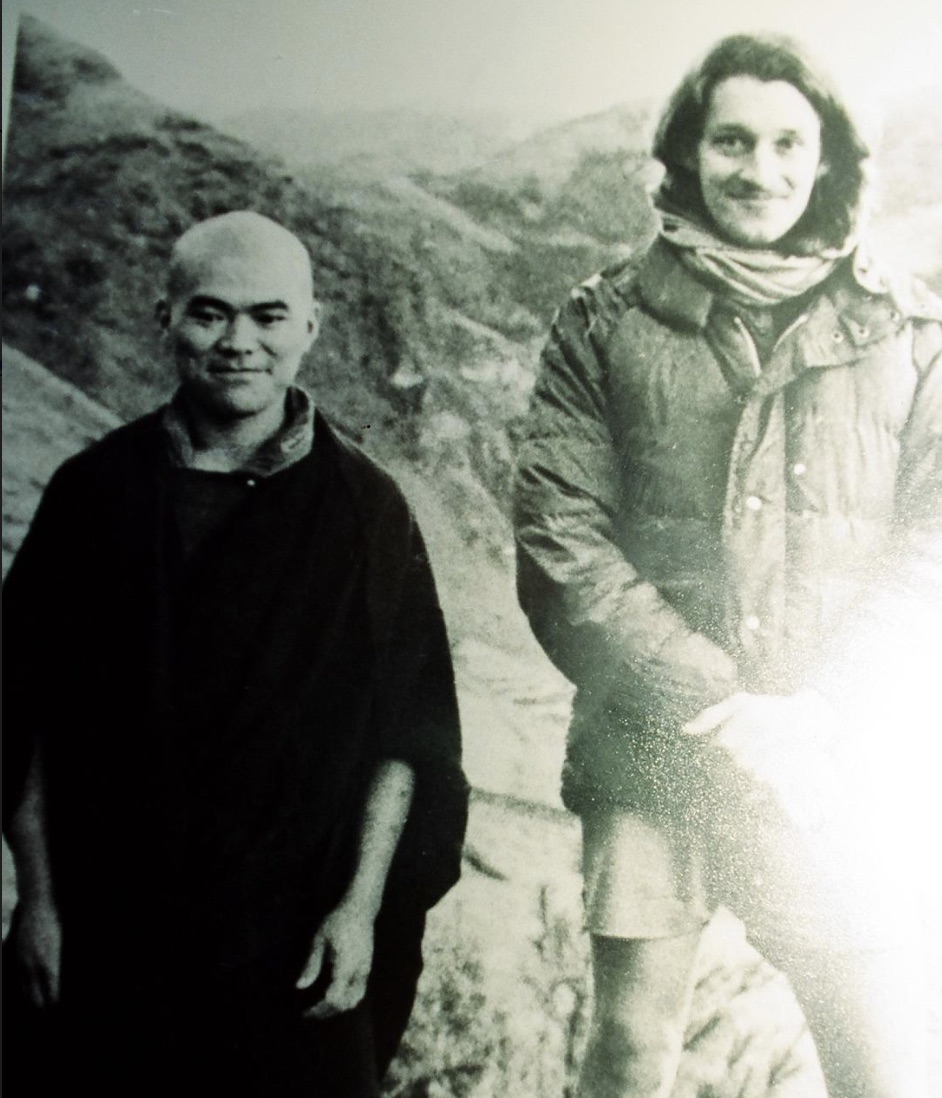

I had wandered down into the basement to sand my coconut bowl in the monastery woodshop, where I met Alan Nicholson for the first time. I introduced myself and asked him why he was “here.” He stated his name and added:

“I am here to end birth and death.”

My topknot almost fell off my head, for here was a straight-laced, short-haired, redheaded carpenter telling me why the buddha taught the dharma, and it had nothing to do with being a cool yogi-looking guy, sitting around indulging himself in a meditative stupor that only served to bolster his ego.

Alan’s words set the stage for serious inquiry. I stayed in the monastery for 10 years, Allen, three decades longer. I will never forget the gift of his words.

Buddhism teaches that all things arise because of conditions and we all ripen according to our karma. The soil in which we grow may be different, but deep down we are all yogis.

I looked the part but wasn’t. Allen didn’t look the part, but was.

Appearances are deceptive. I was fooled by my own image; a game Allen didn’t bother with at all. He was ordinary in every way, save for a thirst for truth under an enlightened master, who was to become mine as well.

If this tale has an essential “takeaway,” it would be: to dive beneath the surface of ego driven propensities, in my case wanting to be a yogi, an enlightened master is essential. Without that, spiritual arrogance can fool almost everyone, and does.

Read 1 comment and reply