“Hey! Hey! Hey!

Give me an I-M-P!

Then shout an R at me!

End with F-C-T.”

Now, what’s that spell? Tell me, what’s that spell?

Do you see what just happened there?

First, I didn’t need to tell you that I was going to lead you in a cheer. Yet I trust that you not only recognized it as such but that some of you—be honest—even joined in.

And second, even with letters omitted, by the time we got to the T, you already knew that the word was imperfect. You recognized the word with ease. Though I would have originally felt that there was but a single perfectly worded message that could be used and that it would need to be conveyed in just the one perfect and precise way to elicit the anticipated response, the desired outcome was achieved!

So, could it be that there actually is more than just one right way to accomplish a task and that we neither need to be perfect—nor do things perfectly—to obtain the desired result? Is there really any such thing as perfect—and if there is, might there also be multiple perfect ways to achieve that state?

That may be a bold new concept and way of seeing things for some. It certainly was for me.

Growing up, the most oft-repeated words that I remember crossing my father’s lips were, “If you’re not going to do it right, then don’t bother doing it at all!” This bit of reprimand is all that exists of my paternal family legacy, passed on from my grandfather to his children and then from my father to me. Some might say that the latter option of doing nothing was the perfect out and gave me the choice to just walk away.

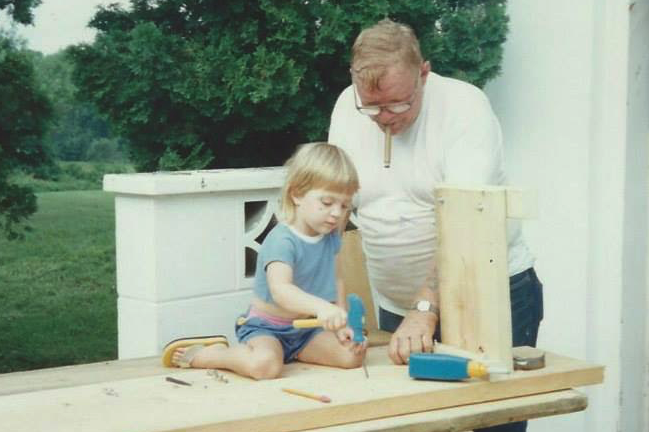

But if you knew my father, you would also know that an out was not in the deal that he put on the table. He had already decided that I was assigned to perform the task at hand—to shine his shoes, wash the family car, or help him with his latest home renovation project. What he was really saying was, “You’re going to do this until you get it right, so whether you do that the first time—or the second, or the third—is up to you; but you’re not going anywhere until it’s done to my standards.”

But how could I know if I was doing something right when I had neither been given the specific yardstick against which my efforts would be measured, nor schooled in the methods that would achieve approval? Where were the guideposts to instruct an eight-year-old in what defined sufficiently shined dress shoes for him to go out on a Saturday night? Or when I was 12, how could I know his expectations of a car washed in such a way that it enabled him to be proud to be seen on the street? Or for his teenage daughter—hijacked for the weekend to help him install a new floor—how could I discern the process to trim a ceramic tile that would fit perfectly into place?

We learn through repetition, and while every task with which I was charged could have brought opportunities for enhanced skills, mastery, confidence, and pride; I was not privy to the rules of the road that would allow me to attain these. I learned through trial and error that the all-encompassing and sole criterion to guarantee rightness in any undertaking was to do everything in the one way that would meet the other person’s expectations—be it a parent, teacher, boss, partner, or other perceived judges of my efforts. I became confident in one belief and mastered the one life lesson to which I had become heir: to succeed is to be perfect and do everything perfectly.

If I could just be perfect all the time, I would have it all: approval, acceptance, love, respect, and success.

If I could just be perfect all the time.

I learned the lesson well but, more importantly, learned that it did not serve me well. And ultimately, I came to realize there was a critical lesson that I had missed.

Fast forward to New York City, 2012. I was 50-something and sitting in a workshop touted to put me in the driver’s seat of my life. The session leader was undoubtedly a cheerleader in a past life, with an introductory exercise intended to gauge our level of commitment and fire us up for the three-day program.

“Are you READY??” Say, “Oh yeah!”

“Are you ready to give me 100 percent for the next three days? Yell ‘Hell yeah!'”

“Are you ready to give me 200 percent for the next three days? Give me a double hell yeah!”

I shouted the responses with the energy of an ardent fan, jumping up from my seat, fist-pumped arms in the air, psyched to start the program and ready to give my all when it struck me.

She wants the same thing from me that my father did.

Her words and methods are different, but the desired outcome is the same. Work hard through every opportunity you encounter and focus on the task at hand. Rise up to the challenges and use your God-given gifts to figure things out as you go along. Don’t give up and don’t give in; give it your all. Leave with new insights, knowledge, experience, and be in the driver’s seat of your life going forward.

Like his father before him, my dad was not an educated man; both had to drop out of school to go to work. My father, aided by a few lies, doctored documents, and a local company desperate to hire a driver, earned his chauffer’s license and began a career driving 18-wheelers at the age of 15. Though he lacked the finesse and sensitivity of my workshop coach, he shared with me—in the only way he knew—the importance of finding solutions, being able to take care of oneself, and summoning the “stick-to-it-iveness” to carry a job through.

Having endured his own broken marriage as well as that of his parents, he knew firsthand that women must often be able to fend for themselves. While his prayer was that my life would be different, he strived to do what he could to ensure that his daughter was prepared to handle whatever life might deliver.

It has been almost 60 years since the days of washing cars and trimming tiles under my father’s watch, and now I know that the pursuit of perfection is a total waste. It is not only unnecessary and unhelpful but unattainable. And as I strive to “un-master” the lesson that everything must be perfect, a wise friend and personal cheerleader reminds me that this response is also one that is indelibly imprinted in my bones.

It is the reaction driven by autopilot and is first to pop up whenever I am asked to perform a task or accept a challenge: “I can’t do this. I don’t know how to do it right. I might as well not do it at all.” While my mouth does not voice these words, they are present in my mind and my bones and have been spoken through the class never taken, the dance not given legs, the business left unventured, and the novel still-to-be-written.

I get no do-overs, nor can I rewrite the history that lives in my bones; I am not in control of the challenges that arise before me. But I can change my reaction to all those situations. The phrase “I can’t” might be my automatic and initial response, but it needn’t be my final thought, nor the one that guides me to action.

With all this new enlightenment, what has changed? Has my Great American Novel been started? Do I still feel compelled to search endlessly until I find the one perfect word or phrase? Does the squiggly red line that Word uses to call out my misspelled words feel instead like it is screaming out my imperfections? Does giving voice to the cause of my writer’s block take it away?

To date, it has taken me two weeks, five days, and thirteen hours to write the 1500 words that comprise the current version of this article.

I don’t write every day, but I think about writing multiple times each day—and in some instances, to bring my fingers to the keyboard. My thoughts have changed from “I can’t write this piece” to “I want to write this piece.” I don’t give in to my doubts; I instead give time to my calling.

In the words of author Margaret Atwood, “If I waited for perfection, I would never write a word.” This inspires me daily and allows me to enjoy the freedom of being perfectly “i-m-p-r-f-c-t.”

Cheers to you, Margaret. And to you, Dad.

Read 1 comment and reply