*Disclaimer: Elephant Journal articles represent the personal opinion, view or experience of the authors, and can not reflect Elephant Journal as a whole. Disagree with an Op-Ed or opinion? We’re happy to share your experience here. This website is not designed to, and should not be construed to, provide medical advice, professional diagnosis, opinion or treatment to you or any other individual, and is not intended as a substitute for medical or professional care and treatment.

Supplements are touted as the natural alternative to medications. We’ve been told over and over again that we need to swallow those pills to balance our diet and boost our nutrition.

Soil quality is poor, foods are transported across countries, and it’s time consuming to eat a nutrient-dense diet. We’ve got to supplement to be able to meet our nutritional needs, don’t we?

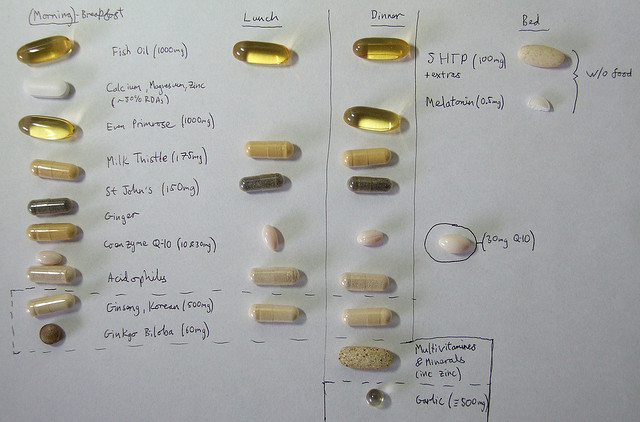

It makes sense to bolster nutrition. But have you ever wondered “what’s going on in those tablets, pills and capsules?”

We don’t hear much discussion about synthetic supplements. Even when I was a health care professional, I assumed that the nutrients in the high-end brand of supplements I was taking—and selling to patients—were extracted from a natural source. The Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) I was taking must have been from oranges or some other food, so that it was in a form my body could easily absorb.

Boy, was I wrong.

There’s a big difference between nutrients from whole foods and the nutrient ingredients used in the vast majority of supplements. After all, supplements are a billion-dollar industry aimed at maximizing profit.

With modern day marketing, many popular supplement recommendations, from the necessity of a daily multi to high-dose vitamin D, are being sold to us.

Take a carrot for instance.

Carrots are loaded with nutrients. Bigwigs like beta-carotene (a precursor to vitamin A) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C), as well as lesser-known players like folicin and mannose. In fact, scientists have isolated about 200 nutrients and phytonutrients in the humble carrot.

These 200 nutrients work together in mysterious ways. The little guys help get the big guys and vice versa—there are enzymes, coenzymes, co-vitamins, minerals, and other factors that help the nutrients work together synergistically.

Scientists don’t know how all this works, and they probably never will. It’s the magic and mystery of nature.

Take a look at the standard multi-vitamin label. We’re content when we see 20 ingredients listed in high percentages. Now think about that carrot again. There’s over 200 known nutrients in that carrot. Foods are complex in their nutrients because nutrients need each other to be properly absorbed and integrated into our bodies.

In our culture, we’re used to the idea that “more is better.” If beta-carotene is good for the eyes, then a whole bunch of beta-carotene must be really good for the eyes.

This type of thinking is not how Mother Nature works when it comes to nutrition.

Foods are balanced. Foods are loaded with lots of nutrients but never in megadose quantities. You’d be hard-pressed to find a food with 1,000 mg of ascorbic acid, let alone the 5,000 mg–10,000mg doses often sold at stores or from health care professionals.

Whole-food whiz Judith DeCava, CNC, LNC writes in her book The Real Truth About Vitamins and Antioxidants:

Natural food concentrates will show a much lower potency in milligrams or micrograms. This is frequently interpreted to mean they are less effective, not as powerful. Unfortunately, the `more is better’ philosophy is far from nutritional truth.

And this:

Vitamins are part of food complexes and must be associated with their natural synergists (co-workers) to be properly utilized and be a potent nutritional factor. In other words, a minute amount of a vitamin that is left intact in its whole food form is tremendously more functional, powerful, and effective nutritionally than a large amount of a chemically pure, vitamin fraction.

In the case of nutrition, “more” definitely isn’t better.

So where are supplement manufacturers getting the nutrients to make their pills?

Most of what’s being sold to us (even the supplements with the healthy folks and rainbows on the label) are chemicals, repackaged in creative ways.

Most supplements contain mega-dose vitamin isolates without their little guy partners, also known as vitamin fractions. Others are simply chemical compounds made in factories, also known as pure, crystalline vitamins.

Both are synthetic and both are a detrimental to long-term health because they’re man-made, not nature-made.

Mother Nature knows best. Nutrients need each other to work effectively in our bodies. The big guys need the little guys just as much as the little guys need the big guys.

When we take supplements in high doses or in isolation from their natural counterparts, there will be consequences. Initially, our bodies might do well with these synthetics because of our extreme deficiencies. But over the course of time, synthetic vitamins can create even deeper deficiencies.

DeCava notes that synthetic Thiamine (B1: a common chemical ingredient of most standard multivitamins) “will initially allay fatigue but will eventually cause fatigue by the build-up of pyruvic acid. This leads to the vicious cycle of thinking more and more Thiamine is needed, resulting in more and more fatigue along with other accumulated complaints.”

But perhaps this story of a medical doctor held captive during the Korean War [1950-1953] is the most telling example:

After a period of time with a poor diet, his fellow prisoners of war began to show signs of beriberi, a disease that results from a severe thiamine deficiency.

After contacting the Red Cross, they sent him some vitamin B1 in the synthetic form, Thiamine HCL. What happened to his patients with the pure-crystalline fraction? They continued to decline.

In fact, the plague worsened until that same doctor listened to a couple of guards who told him that rice polish (known today as rice bran) could be used to alleviate the symptoms. The doc started feeding his patients the rice polish one teaspoon at a time. Within a short period, his patients’ improved and the beriberi plague ceased.

The bottom line is that nature’s nutrients are packaged to perfection. A simple teaspoon of rice polish outperformed a high-dosage, synthetic compound.

Does this mean we have to throw out our supplements altogether? Not so fast.

First we need to know the difference between whole-food concentrates and synthetic supplements. It’s all in the label.

Read the ingredients. The ingredients tell it all. If a nutrient is listed as a food like liver, pea vine, or alfalfa, you’re good to go. If there are chemical names like niacin, thiamine, or tocopherols, throw it out.

In nature, B vitamins come from the likes of nutritional yeast and liver, not niacin or thiamin. Vitamin C comes from green leafy vegetables, citrus, and buckwheat juice, not ascorbic acid. You’ll find vitamin E in wheat germ oil and pea vine, not in tocopherols.

Look at the Dialy Value (DV) percentage. The percentage of Daily Value is based on chemically pure vitamin fractions. If the nutrient on the label is listed at 100% or more, you know you’ve got a synthetic product on your hands. Remember, nature is low dose but highly potent.

Beware of singular vitamins. Mother Nature works in tandem. Her nutrients are never found alone. If you’re taking a supplement all by itself, such as vitamin E or D, it’s guaranteed to be synthetic.

Don’t buy the hype. The supplement industry is an industry just like anything else. Major supplement manufacturers often sponsor studies and/or donate money to research programs at universities likely having some influence on both the study design and the results and conclusions reached.

The simple truth is that profit margins are much higher when manufacturers replicate standardized compounds rather than go through the careful, labor-intensive, more expensive process of compounding whole foods.

When it comes to supplements, it’s safer to stick with intuition and follow Hippocrates’ advice: “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.”

As always, it’s great to hear from you in the comment section. I wonder, what’s your experience with supplementation? Tell me, have you had great success taking a supplement or have you noticed your health starting to slide?

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Richard Lewis/Flickr

Read 8 comments and reply