It took me nearly a lifetime to learn that certain people can “read” —that is: feel; detect; absorb; be barraged, besieged and possessed by—other people’s emotions without even realizing that they’re doing so.

It happens not by choice but because these involuntary feelers—who, in paranormal circles, are called “empaths”—possess a psychic power lesser-known than, say, telepathy or precognition.

Without so much as a word or glance exchanged, empaths can feel—as if being electrified—the hidden rage, joy, sorrow, shame, regret, grief and/or fear being experienced by anyone nearby, including random passersby and even animals.

Empaths feel others’ feelings so completely and so suddenly that—unaware of their own powers—they often mistake these feelings for their own. Not understanding why, for instance, they suddenly want to scream in supermarkets or sob during birthday parties, empaths too often denounce themselves as moody, even crazy.

I know this because (a) commonly wanting to scream in supermarkets, and (b) long believing myself crazy, I (c) finally learned about empaths, and that I might be one.

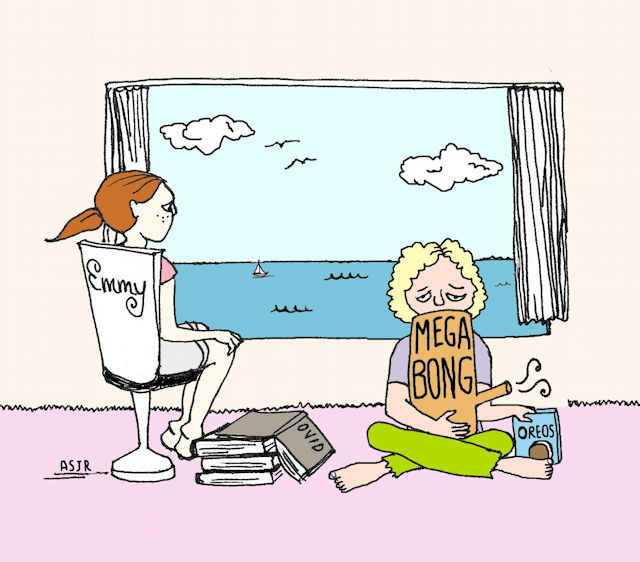

That’s why I created a cartoon stories about one of us: Meet Emmy. She’s an empath.

Emmy dreams of wildernesses.

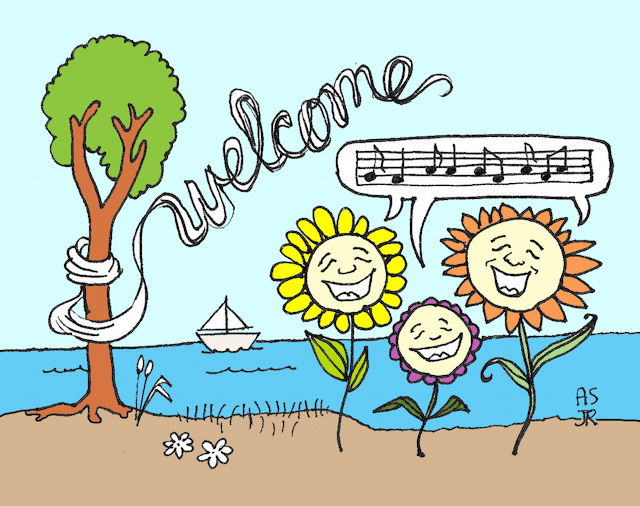

Many empaths do. They yearn with paralytic urgency for forests, deserts, shores. Why? Because wild plants, wild creatures — even rocks, water and sand — shoot healing rays and exude greetings that only empaths can hear? Is it because, in crowded places, empaths feel besieged by flying feelings—but in wild ones they’re nearly alone?

When Emmy shuts her eyes, she sees the sea. She grew up in one beach town, went to college in another.

Living near the beach is like having an IV hookup that you take for granted, forgetting that it keeps you alive.

It is too easy to leave paradise.

At twenty, Emmy did, never suspecting that she might never return, that circumstances would compel her to live in a non-beach town, perhaps forevermore.

But hey. At least she doesn’t live in Omaha or even Reno. Emmy lives two hours by public transit from the beach. Quicker by car, okay, but Emmy quit driving at age eighteen, because it requires hive-mind.

When Emmy has enough time — almost never — she visits the beach. Given how rush-hour public transit affects empaths, each trek is a sacrifice. Which Emmy makes for fear of going mad.

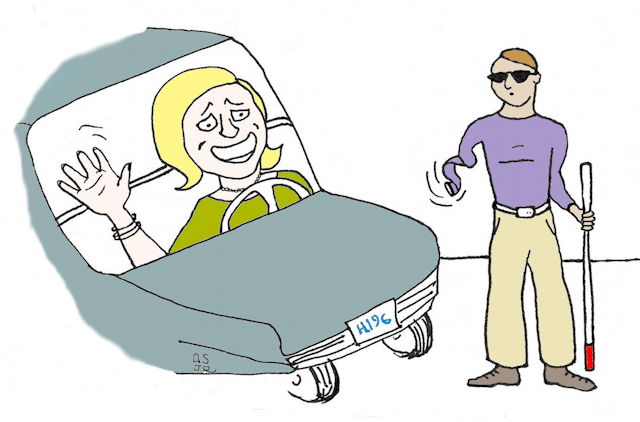

Walking to the subway station in the town where she lives — a famous town given to grotesque self-congratulation — Emmy crosses a street near a one-armed blind man (all descriptions in this narrative are true) as a car rounds the corner and roars halfway through the intersection before screeching to a halt. Not having noticed the pedestrians until just now, its driver smiles sheepishly and waved.

“Close call,” murmurs the one-armed blind man, unable to see the “Coexist” and “Teach Peace” stickers on the car as it glided away. But because in addition to reading others’ emotions, empaths can also see through outside appearances to others’ true selves, Emmy sees more than stickers. She sees straight through the driver’s ostensibly ingratiating grin to the hideous smirking soul inside.

At the subway station, Emmy boards a citybound train.

This is mass transit: strangers forced to sit or stand inches apart, their flesh occasionally touching, as otherwise occurs only between intimates — while speeding underground, underwater or through thin air.

This is mass transit: Metal capsules adorned to appear as unadorned as possible, packed with passengers, each of whom could stroke or slash five others in an instant. Most pretend they do not realize this. They stand inches apart, touching even, as if this was not odd.

But their emotions flare with the strength of a thousand suns.

This is truest during morning commutes, because the act of traveling to work is a series of traumas, which commuters undergo day after day.

Waking up to alarm clocks is traumatic. Leaving bed abruptly is traumatic. For some, choosing outfits, getting dressed and looking into mirrors is traumatic.

Wearing “work clothes” is traumatic, because one would not otherwise wear these clothes. As real or would-be uniforms, as enforced conformity, work clothes are traumatic.

Leaving home is as traumatic now as it was for our prehistoric ancestors, leaving their caves. The iPhone is merely a modern spear. Away from home, we are soft targets. This fact is traumatic. Striving to deny it is traumatic too. And leaving loved ones, feeling forced to say farewell at 6 a.m. and simply trust that all involved will reunite by nightfall, requires monumental faith. That front door clicking shut behind you is traumatic.

Public-transit systems seem designed to traumatize. While jostling each other and staring straight ahead, passengers face countless unseen threats: Microbes throng every seat and handrail. (Why, just yesterday I saw two men picking their noses openly on buses, then wiping their hands on the upholstery.) Imagining the fates of public-transit vehicles during earthquakes, fires, floods and acts of terrorism is traumatic. Playing Flappy Bird can distract one from picturing oneself impaled by metal rods only so much.

All this, plus work. What’s worse: hating your job, or loving it and dreading losing it? All jobs entail responsibility, whether it’s brewing coffee, mixing concrete, selling stocks or amputating arms. Responsibility is trauma. There, I’ve said it, because nobody else would. Decent adults accept responsibility — thus traumatize themselves.

Day after day. Year after year. All this collective trauma swirls around commuters like storm clouds.

On mass transit, you get all this, plus twenty million other sorrows and desires. This is why riding mass transit in the morning feels, to empaths, like playing dodgeball in the Tower of Babel while wearing electrodes and being “it.”

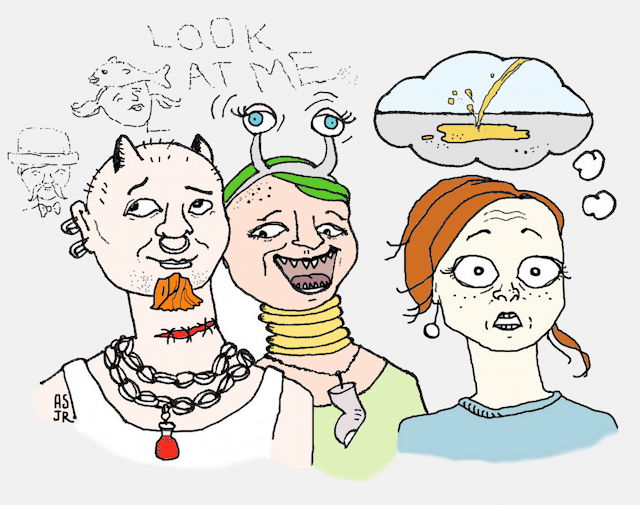

Reaching the metropolis, Emmy transfers to a tram. She can feel the air thickening with urban angst.

Each city has its own particularities. The one across which Emmy rides to reach the beach is known for its freedom of choice and its free spirits. Emmy applauds freedom. But from some ostensible free spirits she detects not art or inspiration but sheer, striving-too-hard desperation — which, to Emmy, smells like pee.

This city heaves with panic, pretense, illness, madness and other intensity. As do all cities. Which for all their arguable beauty makes all cities scary and epically, centuries-lastingly sad.

That’s why Emmy hates cities. So. Much.

As I know. She wishes she lived somewhere small whose name hardly anyone knows. But she resides near this metropolis, has worked in its skyscrapers and speaks of it with faux awe because such reverence is expected of her. And she hates herself for this.

Too many empaths blame themselves too much. Not only do they mistake floating negative emotions for their own, but also—when their real, authentic feelings might in any way seem hostile, illogical and/or antisocial—empaths castigate themselves.

An empath might say: Cities drain and depress me because a simple arithmetic fact is that so many people feel so intensely in cities, doing so many intense things at exactly the same time.

An empath might say: Hating cities (because I hate being drained and depressed) means I am a crazy, misanthropic, maladjusted, intolerant, feeble freak.

This is not funny. It should be, because it’s a cartoon. But it’s scary and sad, because cities are scary and sad. Public transit is scary and sad. Humankind is scary and sad — even, sometimes, when it is happy. Emmy knows this, as all empaths do.

Emmy rides the tram past skyscrapers, homeless shelters, colleges and hospitals. In her microbe-slick seat, she’s surrounded by shoppers, students, stroller-pushing parents, people who are visiting the sick or sick themselves. Churches, judo schools, restaurants (which serve tempura tacos and bone-marrow burgers) and pet shops roll past. To Emmy, this feels like asphyxiating in a Jell-O lake while having a tooth drilled and wanting, faintly, to jump off a cliff.

And Emmy wonders: Is this worth it? Very nearly not. She scolds herself: Stop whining, brat! Be grateful for possessing the $11.50 round-trip transit fare! For having a home and significant other to return to! For having a sandwich to eat very soon while remembering the childhood joke: What will we eat at the beach? The sand which is there! Sand. Which.

Emmy thinks: I should be grateful for fifty thousand things, including the fact that, unlike my cousin, I am not afflicted with cyclic vomiting syndrome.

Yet the equation stays the same: To regain paradise for just an hour or so, to re-insert that life-saving IV (knowing it will be ripped out soon), to reach the clean surf-and-sand landscape (rain or shine) where (there and only there) she feels neither ill nor at war but dazzlingly sane (so rare), this empath must endure hammering, heart-exploding, flayed-alive exposure to the city, two hours out, two back.

Tick tock. Emmy thinks: The beach is not worth this.

“End of the line,” shouts the driver.

And —

Relephant:

What it Means to Have the Heart of an Empath.

Author: Anneli Rufus

Editor: Renée Picard

Images: original illustrations from the author

Read 3 comments and reply