Sundance: the ancient ceremony that rocked my world.

But I cannot talk about Sundance without first talking about my uncle.

While he has been in my life as long as I can remember, I did not get to know him until I was in my 30s.

I was at a family event telling him about the conflict my wife and I were having with another part of the family. (See my article, “8 Words that Create Conflict and How to Stop Using Them” for more details.) Although my uncle ran a landscape company in a small Texas town with my aunt, it turns out that he was a trained Jungian psychotherapist, and before I knew it we were meeting weekly. I learned that he was part Native American, and had embraced much of the Native American way of thinking and being. His advice, teachings, and ceremonies were full of traditional Native American wisdom. I simply could not get enough of them.

One thing my uncle spoke about often was Sundance, an ancient ceremony that begins on the summer solstice each year. He is a member of one of the tribes that conducts the ceremony on its reservation, or “rez.” Sundance is a commitment of both time and energy—a pilgrimage of sorts. After many years of saying that I “didn’t have time,” I decided that to make the journey with a small group of Washitu, or Caucasians, traveling together from Texas.

After two days of driving on two-lane roads, through small towns that time seemed to have forgotten, our caravan of four cars arrived at the Cheyenne River Lakota reservation in South Dakota, only to find ourselves navigating nameless roads through seemingly endless pastures. After a few miscalculations and wrong turns, we arrived at the ceremony grounds, and met the medicine man who was in charge. He shook our hands gently, hugged us tightly, and said to call him “grandfather.”

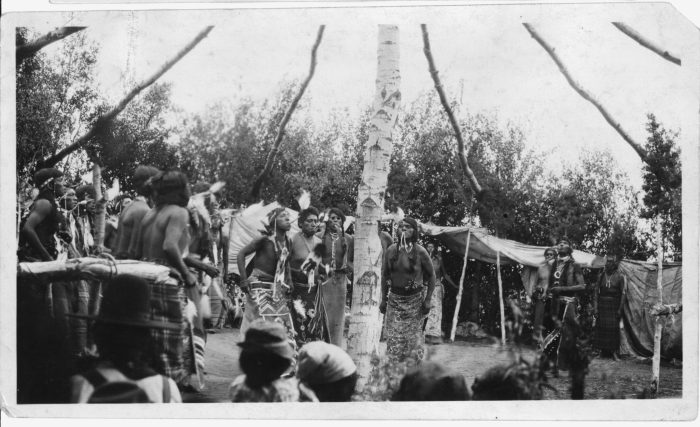

The ceremony grounds were simple, and strongly resembled an ancient stone circle. There was large open circular area in the center, surrounded by wooden poles supporting a narrow roof. The center area was where the ceremony itself would take place, with the covered area being for the audience. At the very center, a huge, freshly-cut tree is installed each year. It is covered in “prayer ties,” which are ribbons the color of the four directions (black, red, yellow, white) that are attached to the tree with twine by the community. Each ribbon encases a prayer and an offering of tobacco. Visually, the grounds were stunning, and I could not look at the tree—covered in so many beautiful prayer ties, each representing someone who is loved—without tearing up. Just beautiful.

Our group, along with many others, camped nearby and ate communal meals served at the “cook house” on a hill above the ceremony grounds. Although our group were the only non-Lakota, the members of the tribe were welcoming and expressed gratitude that we had come to join them in ceremony.

The ceremonies themselves were conducted by “dancers,” who were dressed in traditional ceremonial garb. For the men, this was a long red skirt, a headband, wristbands, and ankle bands made of sage wrapped in red ribbon. For the women, this was a long blue dress, with the same headband, wristbands and ankle bands. Most had a leather necklace holding a whistle that was blown during the ceremony, and carried a long tobacco pipe and eagle feathers.

During the ceremonies, the dancers “danced” a step that seemed to represent walking a path, with rhythmic drumming and traditional Lakota songs in the background. They honored each of the four directions, gave thanks to “Great Spirit” or Wakan Tonka, and paid homage to the tree, or Tonkashila, which served as a kind of altar for the ceremonies. The audience supported the dancers by doing the same steps as the dancers but in place, and raising and lowering their arms in sync with the dancers.

The ceremonies continued for four days and included a naming ceremony for Lakota children, a healing ceremony for the audience, a “skull” ceremony for dancers seeking to break free of their past, and a “piercing” ceremony for dancers seeking to break free of their attachments.

I was surprised at just how powerful these ceremonies were to witness, and how they affected me physically. There were times when I was looking at the tree and all its prayer ties, and hearing the drums and the Lakota songs, and felt so full of energy that I was frozen in place; my body desperately wanting to cry out, “What are we doing to ourselves and this world?” Other times, I felt like I was in a trance, at the mercy of the Lakota songs, the drums, and the dance.

By the time the ceremonies came to an end, my heart was both open and exhausted. I felt overwhelming gratitude for Creator, for the tribe, and for our small “family” of Washitu. After a week of bare-bones camping, with no running water, electricity, or showers, I was also ready to return home.

Of all the things I learned and experienced at Sundance, there were five lessons that stood out, and that I feel compelled to relay as part of what the Lakota call “sharing the medicine.”

Everything is Spirit.

The Lakota believe that absolutely everything is “spirit.” Whether it’s people, animals, fish, plants, trees, water, grass—whatever it is, it is spirit. Even rocks are called “mineral people.” And everything is part of “Great Spirit,” or Wakan Tanka. Scientifically, this is true—everything is made of atoms, with subatomic particles that are in motion, even in the things we think of as “dead.”

Because everything is “spirit,” everything is deserving of our respect and our gratitude. So, if there is a needed rain, they are grateful to the spirits of the wind, clouds, and water that created the rain. If they eat a meal, they are grateful to the spirits of the animals and plants that gave their lives so that they could have nourishment and continue to live.

No Taking Without Giving.

The Lakota believe that nothing should be taken without reciprocation. So if an animal is killed for food, thanks are given to the animal for the nourishment it will provide. If sage plants are cut for ceremony, thanks are given and tobacco is offered to the plant for the leaves taken. If something is requested of Great Spirit, such as healing, an offering of prayer, gratitude, and sacred herbs are given. Sometimes, as part of the ceremony, flesh and blood are given as well by the people. This is quite literally the reverse of the Christian ceremony of receiving the body and blood of Christ.

Peace is always there.

Peace is like the sun—it is always there, but sometimes it is behind the clouds, waiting. Waiting for us to clear away the thoughts that keep us from experiencing peace. Thoughts like, “I am responsible for the suffering of others.” Thoughts like, “I am not good enough.” Thoughts like, “I am not loved.”

We are all related.

The Lakota believe that we are all one people, and have a phrase to express that sentiment, Mitakuye Oyasin, To them, there are no “races” or other divisions between people. It doesn’t make sense to them when one “race” looks at any other “race” as somehow less than. They emphasize this by calling everyone their “relatives,” even when (or perhaps especially when) there is disagreement or a lack of understanding. The medicine man asked us to call him grandfather even though we are not related by blood. This leads to more compassion, and helps resolve disagreements, when they think of others as part of their family.

We can break free from our past and our attachments.

The Lakota believe that there are things from our past that are holding us back from being who we are in the present (like past trauma), and things in the present that we have unhealthy attachments to (like drugs, alcohol, shiny things, or even people). They believe we can break free from these and become who we really are with enough courage, will, and help. Whether this is through physical ceremonies, like the “skull” and “piercing” ceremonies I witnessed, or whether it is through simply deciding to walk away from things that do not serve them, they can do it. Especially with a little help from their relatives.

Post Script

Sundance was a heart and mind-opening experience.

I thought a number of times that I was in the “upside down” because the way the Lakota think is the opposite of the way I had been trained—no, domesticated—to think in some important ways. In the wake of my experience, I am examining that domestication, and asking simple but profound questions, like:

If I believe spirit is in everything, how will my attitude and behavior toward everything in my world change?

If I believe there is no taking without giving, how will my relationships with people, animals, and things change?

If I believe peace is always there, waiting for me, what thoughts will I change that will clear the clouds away from my peace?

If I believe we are all related, how will that change how I feel about my fellow humans?

If I believe I can truly break free of past trauma and present attachments, what is it that is holding me back, and keeping me from being who I truly am?

These are questions that will continue to follow me, and that I hope to answer, as I continue to integrate my Sundance experience.

Namaste.

Read 6 comments and reply