View this post on Instagram

Being “spiritual” can help you find a middle path between religion and science, or faith and logic.

It is leaning into openness to what you don’t know while rejecting the surety of religion, the reductionism of the West, and the false certainty of materialism and atheism.

Nevertheless, going into your practice as a “spiritual” person can create problems far bigger than those it solves. And it can also make you a terrific jerk, a flaming narcissist, or one of those dreaded cacao ceremony people.

Here are five problems with having a spiritual identity:

Problem 1: Making the Spiritual Yours

First, a paradox of spiritual practice. A genuine spiritual experience always gives us a sense of a world beyond our limited ego view…and our ego immediately attempts to make that experience part of its view. This is a human thing to do, so it’s not a bad thing, or something to feel ashamed of doing, or something that’s stupid. We all do it, in one way or another. In fact, I have an honorary PhD in this.

When we try to possess a spiritual experience, we end up corrupting the experience while also making it impossible to transition from an experience we have to something we live. This is one of the main ways that we get stuck—trying to possess our spiritual experiences with our egos.

Bono tells a great story where one of his spiritual mentors told him to stop asking God to bless what he was doing, and instead, “find what is already blessed, and become a part of that.” It was what led Bono to be the humanitarian he is today—because it got him out of a view of spirituality as an extension of what I want.

Related to this is another problem: when we think we’re spiritual people, we tend to think that only spiritual experiences are legitimate, or least worthy of pursuing and honoring. So we try to destroy or get away from petty thoughts and mental stories.

In other words, meditation and prayer become forms of attempting to kill the “bad” ego and its messy emotions and sh*t stories, and so things like jealousy, anger, lust, or shame get repressed because those are considered “lower” human emotions that are not enlightened or spiritual at all. This is a grave misunderstanding, and this view makes spiritual evolution impossible, causes repression of emotion and spiritual bypassing, and can deaden empathy and compassion both for self and for others. It can also make you a pretentious and self-righteous jerk.

It’s worth repeating: it’s a human thing to try to possess a spiritual experience. It’s one of the most human things we can do. Beating yourself up for doing it doesn’t help—and won’t work. I’ve tried. Masochists do not get to the front of the line first, although the ones that do have a “kick me” note attached to their backs. It’s a hard habit to break, but when you do, the universe will open herself to you and share her secrets.

You just can’t keep what you find.

Problem 2: Confusing Spiritual Beliefs with Insights

What is spiritual? Tea with your boyfriend? A sunset booze cruz? Church? “Medicine”? Sitting around in all black clothes in pain (that’s you, Zen!)? I define it as the search for the sacred. I think this is a pretty good definition. By “search,” I mean this is an ongoing journey, a process that begins with the discovery of something sacred hidden right here in the seemingly profane life of a modern human. By “sacred,” I mean discovering a perspective that illuminates some kind of transcendence, immanence, boundlessness, heartfulness, or ultimacy.

But the key here is insight, not belief. It is often said in Zen, for instance, that, “You need to deepen your insight.” This means go back to the meditation cushion, sit in meditation, and see if a deeper illumination can be allowed to arise within you.

If belief is the domain of religion, then insight is the domain of spirituality. The realization of a spiritual insight is more important than having a spiritual belief, in the same way the comprehension of a scientific insight is more important than having a scientific belief.

Spiritual insight can’t be taught, but spiritual beliefs can. The former needs to be fully realized for oneself, the same way that love must be experienced in order to be fully understood, or complex mathematics, or heartbreak, or the discernment that comes with grey hairs. My belief in Godël’s incompleteness theorems is irrelevant because I’ve never had the insight of “limits of provability in formal axiomatic theories.” (In fact, I have no idea what those words in quotes even mean.)

There is an old expression in Zen: you can’t talk about the ocean to a pond frog. In other words, if you haven’t had a spiritual insight that has shown you a truth deeper than egoic belief, there is no more way for me to talk to you about genuine spirituality than there is for Godël to talk to me about mathematical logic.

Spiritual insight comes, in part, from being able to let go of the self—thoughts, feelings, stories, beliefs, and so on. This doesn’t mean that those who have done this are egoless, however—egoless is what an infant is, which is why they can’t hold their heads up, they sh*t their pants, and they need to be fed to survive. Highly realized spiritual masters do not identify with their egos and their thoughts, stories, and feelings, but they of course still have those things. The self and their identities are still very much there—they’re just not held tightly.

Put another way, they’re selfless not egoless. Those great teachers don’t really believe the stories of their own egos any longer, any more than you believe the nightly news anchor is absolutely correct.

These masters experience pain, but they experience a great deal less suffering because they’re not in the habit of resisting the world as it is. Rain is wet, snow is cold, the sun is warm, life ends in death, heartache hurts, love is expansive, and many other things simply happen—without reactivity.

Many of us take up meditation or prayer in order to find some degree of peace in the world, but for most of us, the path is blocked even before we begin. We’ll never move beyond a glimpse of freedom because we’re in the way. Most meditations we learn are designed to give our egos something to do: we count our breaths, we focus on our inhales, we label our thoughts as thoughts and let them go, we come into our body in a particular way, we recite mantras, or we pray.

“In the silence of the heart God speaks.” ~ Mother Teresa

Allow the clarity that is already here to arise within you. Allow God to speak to and through the quietness of your heart. Nothing about identity in that. No crystals or malas needed, no six-part course to take, no two-hour satsang, no week-long retreat, no divinity, no empowered masculine or divine feminine claptrap.

Nothing to sell, and nothing to buy. Zen really is a terrible cult, and a terrible business model.

Pure awareness, or God, or spirit, or Christ, suchness, or enlightenment—or whatever you want to call the Omega and the Alpha and the real goal of your meditation—isn’t responding to your meditations. It’s not affected by your meditation techniques, and it doesn’t come and go. Your ability to sit as awareness itself is what comes and goes. Pure awareness, or God, or spirit, or suchness doesn’t ever become part of you.

God never becomes a part of you because God could never be apart from you. And you don’t become part of it. Awakening is simply awake. God is simply God. God is simply awake. Or go to what is already blessed, not to what you think is—or want to be—blessed. You can’t wake up; you can’t become enlightened because you can’t keep what you find here. But you can allow what’s already here and notice for yourself that awareness is aware, not you.

Problem 3: Attachment to Spiritual Beliefs

You cannot be opinionated and awake, you cannot be liberated and special, and you cannot be judgmental and free. Liberation means without an opinion of any kind, utterly un-special in how you see yourself, and radically accepting all that is, without exceptions.

When the brilliant musician Lenard Cohen went to a Zen monastery in the 90s, he was treated like everyone else, slept in the dorms, and was denied both personal time and any acknowledgment of his specialness. It was just what he needed.

A spiritual identity, you see, might be a better and more helpful identity in stressful times than that of, say, a banker, but not necessarily (and probably not in a financial crisis). But more times than not, when the sh*t really hits the fan, our spiritual identity is just another thought form, another set of beliefs fueled by the ways we string together our musings to create stories and thereby our worlds.

Any egoic identity is created by our impermanent thoughts experienced over time, creating an impermanent identity. We can all think of identities we’ve let go: maybe a counterculture teenage punk, a responsible wife, an angry rebel, a liberal activist, a nice guy, a conservative, a slut or a prude, a man or woman (if someone transitions to the opposite), a gender identity of any kind, and so on. Other identities are fixed, such as ones based on our physical appearance (people of color can’t choose to be white), but they too vanish as death takes them from us.

While an identity can be useful and very much necessary to navigate life and to grow up parts of ourselves, it can be a double-edged sword when it comes to having and sustaining spiritual experiences that happen beyond its reach.

If we look a little closer, we see at its core, identity is made up of thought. And our thoughts are a fascinating place to bring some attention, some awareness. While we can harness our thoughts into practical thinking, on occasion, we are utterly powerless to stop them. And we cannot really control what we’re thinking most of the time, either. If we could, we’d simply choose not to focus on our last breakup, or our mortality, or our sick child, or our test tomorrow, or whatever might be bothering us.

Perhaps we’d only ever think spiritual thoughts (SNOOZE), never have thoughts that upset us (what would we pay our therapists for?), or never have thoughts that end up hurting ourselves or hurting someone else when they’re acted on (also known as the School of Hard Knocks). We’d be the sovereign of our own minds. If you tell the truth, you probably feel much more like the slave to your thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and yes, your identity—spiritual and otherwise.

Said another way: if you can’t find freedom and lasting peace with your thinking mind, how can an identity built on those thoughts and feelings help you achieve freedom and lasting peace?

I am not saying you shouldn’t have an identity—absurd (especially since society may have expectations about your identity that require your attention, care, and action if you’re in a non-privileged position). Thoughts and identities are quite useful, and they’re indispensable to the business of being a human being. But it’s good to keep in mind that your identity, no matter how profound or brilliant or original or righteous or historically oppressed, cannot liberate you from your suffering.

Problem 4: Zealotry of Belief

“Enlightenment is intimacy with all things.” ~ Zen Master Dogen

This statement is really a problem for most spiritual people. We do not want to be intimate with all things—sex trafficking, environmental catastrophe, wildfires, wet swimsuits sticking to your inner thighs, family Thanksgiving, or rush hour traffic.

But if you’re in love with half the world and hate the other half, how do you ever get your mind into a place where you can accept that the deepest spiritual insight that you can have not only isn’t spiritual, but it includes everything in the manifest universe—including all the nasty bits?

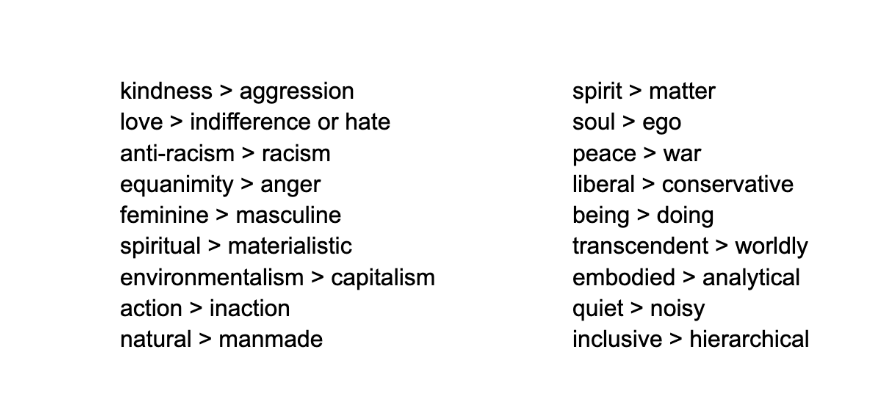

A spiritual identity is unique among our identities because it is trying to find a reality deeper than the one in which it currently finds itself. Typically, spiritual people will share a good deal of these beliefs about the world:

These might seem ennobling to some. Here’s the rub, though: there is nothing inherently ennobling or wise about wanting to improve the world as you see fit, because that goal, like so many that seem good and just, can get hijacked by your nastier, unconscious parts.

Take a peak at the chart again. If you really tell the truth, it’s far more accurate to say that the half you like has more reason to exist than the half you don’t. So then we think we should exterminate patriarchy, abolish capitalism, and be intolerant of the intolerant.

A discernment might be that some of those things seem more expedient on the path of awakening or the path of knowing God, the path of sustainability, the path of inclusion, or the path of compassion. But discernments are free of egoic contraction, defensiveness, judgment, or all around douchebaggery.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting a more peaceful, kind, just, and fair society where more people are aware of the impact of mindless consumption, unconscious power structures, and their behavior on the larger world. These are noble and powerful goals—discernments—to have and to work toward.

The problems arise not because we want to make the world a better place. It is when we are attached to our way of doing it, to our opinion of the world as it is. “F you. I’m right, and you’re wrong, and you’re not only a piece of sh*t, you’re part of the problem.” This is not “intimacy with all things.”

To state the obvious: it’s okay to want to make the world a better place, but it’s also much more complicated than that. We assume, as “spiritual” people, that we would all agree on what it means to make the world a better place. But many of the most diabolical dictators in history, and the most abusive cult leaders, were convinced they too were doing exactly that.

This is a problem with a spiritual identity: it desires and believes in the superiority of “spiritual” things, like nonviolence over violence. Or environmental sustainability over capitalistic industry. As a citizen, an activist, or a concerned human being, there is nothing wrong with having these opinions and in fighting for them. I’m certainly not suggesting we allow rampant corporate control of our government or systemic racism to continue, or that there is something wrong with being in opposition to those things and fighting to remove them as much as possible from our culture.

As a spiritual practitioner, however, your attachment to your opinion is, quite simply, toxic on the path. Believing that one half of the world (the half you like) has more reason to exist than the other half of the world (the half you don’t) is hugely problematic because that thing you hate continues to exist no matter how you feel about it. The world, you see, is not divided. Only you are, and only you project that division outwards where it doesn’t exist.

Problem 5: Refusing to Accept What Is

Activism, then, comes from a place of radical acceptance of what is.

Acceptance of things as they are doesn’t mean we have to let polluters pollute, racists run police departments, despots run countries, and rapists rape. That is not at all what this means. When we look out at the world from an awakening state, we’re simply not at war with what we see there already existing—and we’re not at war with those parts of ourselves that refuse to accept it.

We accept the world as it is even as we work to change it, and even as our hearts break open at the suffering we encounter. Compassion for the pain of the world as it is now will take you to your knees as your heart breaks—without having to turn away from it in judgment and contraction, in anger and disbelief, in numbness or fatigue, or in a righteous rage. When you’re one with the world, you’re one with the world’s pain.

Accepting the world as it is doesn’t mean doing so with a smile, although truthfully you may find yourself smiling a great deal more often when you’re no longer at war with what is.

Getting Over Yourself

You cannot ever find liberation and peace with your opinions, beliefs, or judgments about the world, other people, or yourself. Those things are the domain of ego, and ego is the domain of division, by its nature. Ego is necessary and we don’t want to try and kill it or overpower it, for who, exactly, would do that? (Ego fighting ego.)

For those who are serious about awakening, I advise sitting with the idea that the universe is undivided and whole, by its very nature, and we are not separate from—nor can be separate from—that truth. You are not separate from the things you want to “exterminate” or “abolish.” So the lie you believe is that you are separate, which you are not. You are as much a part of the world and everything in it, and the universe, as every other part—undivided, whole, and complete unto yourself.

Your ego will go on making noise. That’s what egos do. Don’t try to quiet it, which only puts fuel on the fire. Let it have its opinions, its judgments, and its beliefs, and know that you are so much more than those things. You are, after all, one with all, both part and whole at the same time. You are free, utterly, right now, even if you don’t know it and don’t believe me.

The practice, therefore, is to just pretend it might be true, and to see if that creates insights of your own, insights deeper than beliefs can ever be.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

Read 5 comments and reply