{*Did you know you can write on Elephant? Here’s how—big changes: How to Write & Make Money or at least Be of Benefit on Elephant. ~ Waylon}

~

For as long as I can remember, I’ve reached toward nature with little thought to the risks. For better or worse, my desire to be close to wildness has always beaten out my primal fears of things like dark caves, rough waters, and dangerous predators.

This desire has led me to some of the most extraordinary places on earth—including one of the oldest human pathways on Earth, a place where our earliest ancestors once walked. The narrow, rocky path, colored red from ochre, spans a huge cliff overlooking False Bay.

This great bay is the Serengeti of the Sea, traversed by whales, orcas, dolphins, and huge fish shoals. By some miracle of fecundity, the bay is still full of life despite three hundred years of hard fishing.

I’d trod this ancient path many times, but this day was something special, a perfect storm of events that allowed access to a very rare place, and I was excited to share it with my son Tom and our friend Pippa.

We descended giant vertical sandstone steps very carefully—each step was so tall and steep and a fall would be fatal. We all felt relief as we reached the edge of the sea where the cliff continued into crystal blue water.

We walked around a small headland, and there it was: the sea cave of secrets.

The cave announced itself with a thunderous boom! caused by rolling waves and the release of air trapped in the dark interior.

The cave was huge and foreboding, and I had a scary memory of a visit when I was flung about in the back before managing to escape, scraped and bleeding but not broken. Normally the water is extremely murky—sediments collect and are forced into the water column by the fierce currents. But a rare upwelling of 53-degree water had flooded the cave the day Pippa, Tom, and I arrived. I could see fish rising from the depths and grabbing food from the surface.

“It’s so clear I can see that rock crab on the bottom,” Pippa cried.

I had never seen the water like this, and I knew we might never get another chance this good.

We slipped into the water, trying not to create pressure waves that would alert animals in the depths, then we swam toward the deep darkness of the cave mouth.

It’s such a powerful place, here on the edge of Africa. The cave itself felt alive, a creature of unknowable age excavated over millennia by the battering of millions of swells that carved deep into the towering cliff. The pungent stench of cormorant guano mixed with the slightly fishy scent of otter spraint.

We were immersed in primal sensations: the icy water, the wild smells, and the vision of swimming into the giant cave creature’s mouth. The light reflected off the seafloor, and dancing on the surface were hundreds of cigar comb jellyfish, their cilia creating iridescent light shows.

My flashlight illuminated a huge underwater passage big enough to park several cars. We followed this tunnel deep into the cliff and looked back at the entrance far away. The vaulted ceiling shimmered with reflections from the water and my flashlight, rippling snakes made of light.

We turned around and swam to the deep place where I’d been thrown about before. Here, the water was so black I could hardly see my hand in front of me.

My primal mind saw this darkness and screamed, Get out! In past times, especially in rivers, big predators would have used their superior sensing systems to “see” us in the dark water and pick us off like ripe berries.

I registered the fear and thanked my primal mind for the warning.

For me, managing fear—any fear, but especially of wildness—is all about getting to know whatever it is you’re afraid of. It’s also about getting to know your limits. Most fear is of the unknown, after all.

Get to the root of some of our species’ most common fears and you’ll find intelligence there—a brilliant survival mechanism that helped wild people and animals survive. Consider a fear of deep water—the sea can be very dangerous until one gets to know her moods, so there is wisdom in approaching her with caution.

Once you understand her ebbs and flows, however, you can make decisions that factor in the force of the wind and tides, the temperature of the air and water, as well as your own strength and energy levels. What was once foreboding becomes a powerful friend that you treat with respect and care.

Our fears connect us to our wild animal kin, who experience fear and danger all the time. Primal fears are life givers, even though the things we fear occasionally take a life. The great irony here is that the forces of the wild are the very things we need to invigorate our beings.

I don’t believe we can chase our primal fears away or deny them any more than we can stop the waves from crashing against the shore or tell a cat not to hiss when her tail is caught under a branch. But we can befriend the primal mind, speak to it the way you might your beloved dog who barks at a visitor. Thank you, but there is nothing to worry about today. This is a way of speaking across time to our ancestors, who knew perils we will never know but who also knew a kind of life that our tame modern world has tried to snuff out.

It was so calm and clear that day, I couldn’t believe our luck. In the pitch dark my flashlight beam picked up a large dark body moving gracefully through the water.

A predator, my primal mind warned—until I saw it was a gully shark, an animal Tom and I knew well and have dived with since he was tiny.

Yes, a predator, I thought, but also a friend.

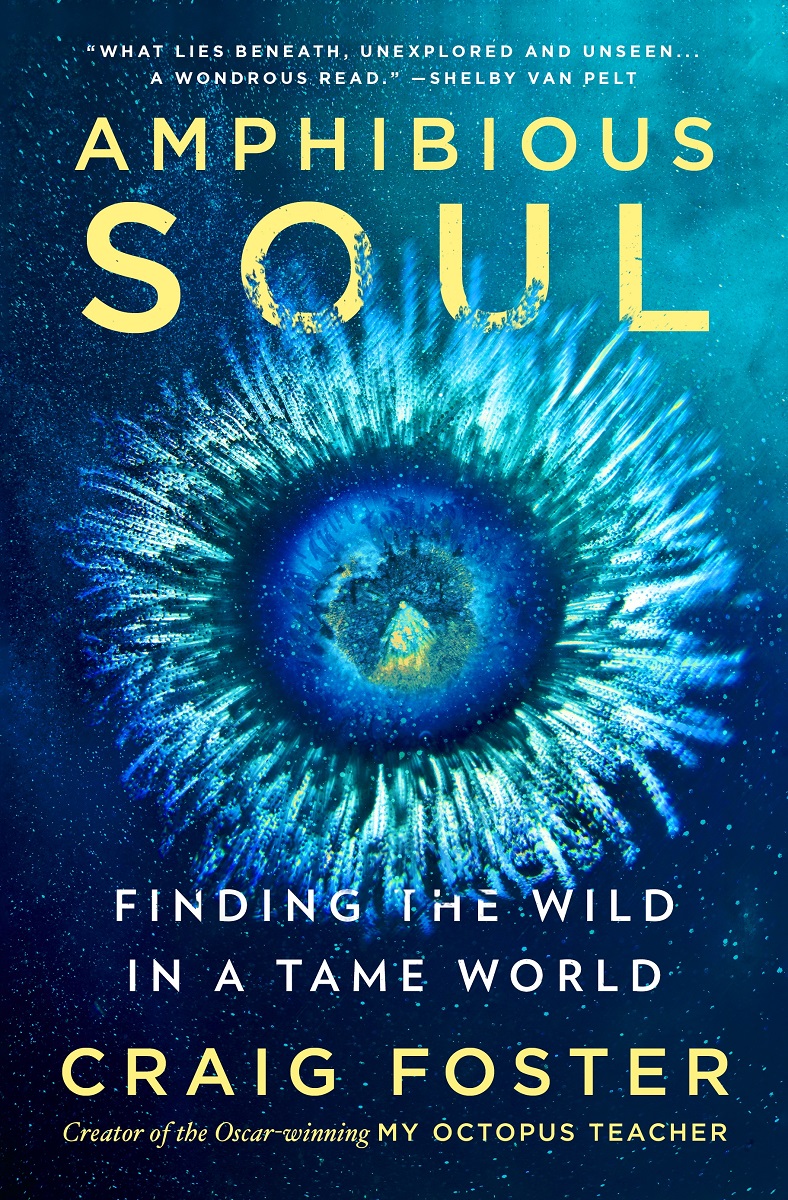

{Adapted from Amphibious Soul: Finding the Wild in a Tame World by Craig Foster and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2024.}

~

{Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.}

Read 0 comments and reply