Repeat after me: “I am not an expert!” Again: “I am not an expert!”

Part 1: I’m no expert.

Obviously, you may in fact be an expert, but probably only about one thing.

If you have studied one specific topic extensively, reached the highest levels of education, and spent your career working in that field—then you might be considered an expert.

But the simple fact is the world is incredibly complicated, and there is more knowledge out there than any single one of us could ever possibly hope to grasp. It is impossible for you to be qualified to understand everything in the world (or even a majority of it). In just about every topic in the world, you are not an expert.

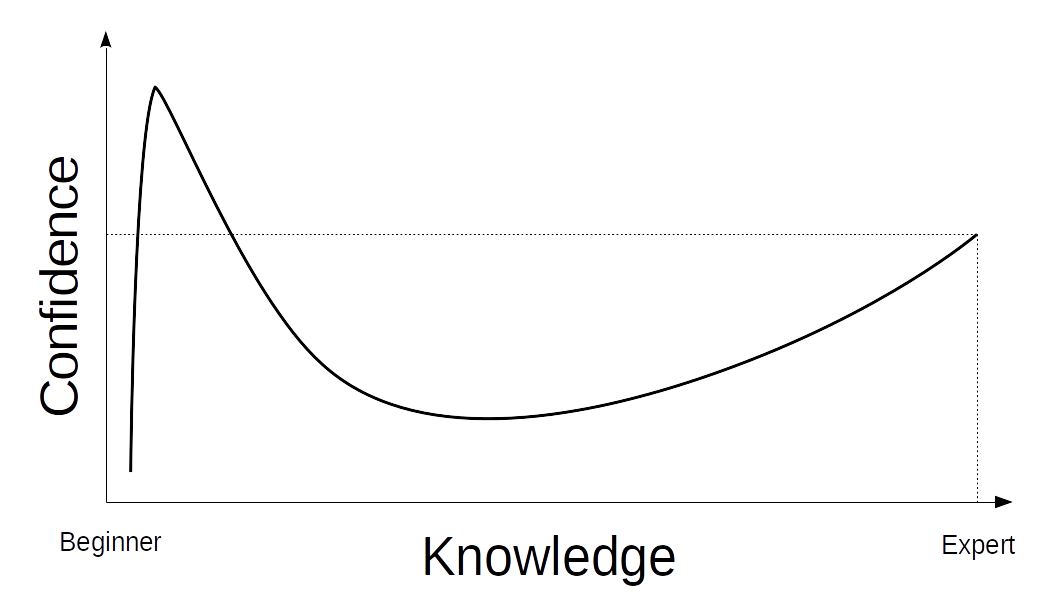

There’s this thing called the Dunning-Kruger effect that suggests that when we learn a little about a topic, our confidence rises quickly (exceeding our level of competence), but the more we learn, our confidence level drops dramatically (as we gain enough knowledge to realize how much we don’t know, and recognize that we aren’t as competent as we imagined). Eventually, if we keep studying a topic, and begin to reach a level of expertise, our confidence rises once again, this time justifiably.

It essentially points out our tendency to overestimate our abilities, to think we know more than we do, especially when we only know a little bit about a topic.

There is a whole lot of information flying about in the world today, and so many important topics rushing through the news cycle. Articles, video clips, podcasts, interviews, memes, books—does anyone still read them anymore? So much content. As different topics come in and out of focus, dominate headlines, get loads of media attention, and trend on our feeds and algorithms (but almost always in short, intense bursts), I am noticing that there is a tendency for us all to learn a little bit about a whole lot of different topics.

There is something cool about that—there is certainly enough to keep us interested, always something new to learn. But the danger is that when we start learning something new, we go shooting up that Dunning-Kruger slope of confidence, and we never keep at it long enough to come down the other side. So everyone starts to have an inflated sense of their own knowledge and competence about a multitude of topics.

Look around. Can you see it? No one will shut up about anything. Everyone thinks their opinion is so important. People don’t hesitate to spout off authoritative sounding rants about topics they started learning about yesterday. We’re all guilty of it, to different degrees. Me too. (Oh my god, am I doing it now?) Everybody feels like they know best. And more than being just a mild annoyance, it’s leading to a point of crisis in our societies.

Part 2: Trust.

One of the most essential elements of functioning societies is trust. We have to trust the expertise of others.

As I said above, there is more knowledge in the world than any of us can ever hope to grasp on our own. That’s why we have specialized fields. The more knowledge we have gained throughout our history, the more specialized those fields become. That specific knowledge is then distilled into the institutions that allow our society to function. At this stage in history, our societies tend to have developed pretty complex systems that involve a large number of bodies working together to form functioning industries.

You trust these systems, and the specialized, expert knowledge of others, every single day of your life. Maybe it’s just an implicit trust, and you’ve never really thought about it, but you do.

Every time you walk into a building, you are trusting that it has been constructed to a certain standard so that it won’t fall down. You are trusting the engineering knowledge that allows us to calculate load capacities and structural integrity, you’re trusting the educational institution that trained the engineer, the licensing body that tested their competence, the regulatory authority that sets the safety standards for all buildings, the inspectors whose job it is to make sure those standards are followed, and the governments that set the policies and oversees those regulators.

The same goes for the plumbers, architects, surveyors, builders, electricians, concreters, and manufacturers of raw materials. There are a huge number of bodies and complex systems operating behind the scenes that we usually take for granted (unless we work in that field ourselves). And that’s just one example! The same is true when you drive a car, when you cross a bridge, when you fly on a plane, and when you eat food and drink water.

That is the world we live in. Every single aspect of your life involves trusting the expertise of others and the institutions we have built and put in place to ensure our society functions.

A pertinent question is why do we trust them?

The answer is because most of the time, they work!

If buildings kept falling down, we would probably think twice every time we walked into one. But more than that, we would change the system! No system is perfect, and occasionally things go wrong. But when they do, we investigate the cause and use the knowledge we gain to improve the system. That’s how we have ended up with these systems in the first place, and why there tend to be so many checks and balances (licenses, standards, regulators, inspectors).

That is not to say that these systems and institutions are infallible. They aren’t. Mistakes do happen. Things can slip through the cracks. There is always an element of risk (sometimes buildings do fall down), but we have to look at the balance of risk.

If all or even most of the buildings we built fell down, we’d have a huge problem. It would be a good indication that there was something majorly wrong with the system we have in place, and we probably wouldn’t trust it anymore. But the fact that building collapses are incredibly rare in our society indicates just the opposite. The fact that buildings used to collapse more frequently should reinforce this to us even further. Buildings are not inherently safe just due to our common sense about how we should knock them up. We have built a system that has improved over time due to robust mechanisms of monitoring, investigation, revision, and regulation that have actively decreased the inherent risks.

As a result, in general, we’re quite comfortable going about in the world. This is because our history, observations, and (most importantly) the data we collect all tell us that the systems we have built generally work. The risk calculations work out in their favour. We trust the institutions.

Part 3: Skepticism versus distrust.

That trust is incredibly important to the functioning of our societies.

Think about it for a minute: without that trust, it’s just you against the world.

If you decide that you can only trust yourself, it’s up to you to do everything. You’d probably end up a lot more independent and probably quite competent at a whole range of different things. Enough to get by. You might work out how to grow food, tend to animals, fix engines, build shelters, and a hundred other fairly useful things.

But it’s quite unlikely that you’re going to be able to perform open heart surgery, build smartphones, generate electricity, fly a plane, explore space, study subatomic particles, or even mine the elements or manufacture the components necessary to even start doing any of these things! Think about all of the things you’d lose. All of the incredibly complex, intricate knowledge that you’d be missing out on. We would regress to the dark ages.

We need each other. And we need the institutions that collate, store, and safeguard our collective knowledge.

So what, are you saying that we just mindlessly trust and accept everything that anyone tells us?

No, not at all. I’m all about skepticism and critical thinking. It’s the basis of the scientific method, which is the basis of all of our knowledge about the physical world. But a big part of the scientific method is about trying to account for and eliminate our own biases and assumptions. We have to acknowledge our own shortcomings. Skepticism is about being led by the evidence, and trusting what works. It’s about accurately calculating the balance of risk.

Science is not dogma or ideology; it is a method of questioning. There will always be an element of uncertainty in any scientific endeavor (however small). That being said, there is a whole branch of science and a whole field of experts (statisticians and data scientists) dedicated to determining acceptable margins of error and uncertainty within data sets (otherwise known as statistical significance).

To demand absolute certainty is folly. However, those small elements of uncertainty are often exploited and magnified by bad actors to convince us (or those of us who don’t have the expert education to calculate statistical significance and margins of error) to discredit robust results and data sets.

If you demand certainty, your result will only ever be distrust. Skepticism is not just blanket distrust. If we reduce it to that, we are in grave danger. We begin to discount expert knowledge, and rely on our own overinflated confidence (usually overestimating our competence). That’s why I think one particular phrase that I hear very often these days is actually incredibly dangerous:

“Do your own research.”

In most cases, you are absolutely not qualified to do “research” or even capable of properly understanding most specialized research that others have done. You’re just not. Sorry. Neither am I.

If you think that you are, you are probably vastly underestimating the depth, complexity, and sheer amount of specialized knowledge in the world, how hard people have to work to attain it and become any kind of an expert, as well as vastly overestimating your own abilities.

Just because you have access to information and data does not mean you have the requisite skills and education necessary to interrogate and interpret that data correctly. The proliferation of access to information via the internet does not make experts. Years of tertiary education and industry experience makes experts. The internet just creates a delusional cognitive bias in us to make us feel like we can all be experts. We’re all prone to do it. We all think that we know best. But we don’t.

If you, as a layperson, think that you’ve thought of something or found some information that all of the experts have missed, it’s probably because you’re at the height of that Dunning-Kruger slope of confidence that isn’t actually supported by deep knowledge or real competence. In most cases, you’re probably just wrong.

Our default position should be to trust institutions that work.

When the balance of evidence all points in one direction, when the majority of the experts agree on something, when all of the different elements in that complex system reach the same overall conclusion, our default position should be to accept it. It should take extraordinary evidence accepted by a majority of experts to turn us against it. The idea of accepting scientific consensus is not about majority rule, or the most popular opinions being the best, it’s about relying on information that has persuaded those who are the most qualified to understand it. If evidence is credible, and data is robust, it should convince the people who actually know what they’re talking about. Scientific consensus is primarily about a consensus of evidence (i.e. a large majority of properly reviewed studies and different types of data all supporting the same hypothesis, or leading to the same overall conclusion), which then leads to a consensus amongst experts, which is then reflected in the institutions.

One of the important functions of our institutions is to filter out bad information. There are flawed studies, there are mistakes, there are kooks with qualifications (plenty of them), there are bad actors—there is such a thing as bad information.

But the whole point of the institutions and systems we have created is to filter them through an appropriately qualified, knowledgeable set of experts to determine whether or not that information holds up to proper scientific scrutiny. In this way, the institutions function as gatekeepers, keeping out an endless barrage of misinformation. The reason you need to be careful about believing information you hear on the internet (particularly when it contradicts the advice of a majority of experts) is because it has bypassed that entire system. And quite often, the reason it is bypassing the system is because the information has not been good enough to convince the bodies of experts or sway the institutions.

Part 4: Surprise, this is about vaccines.

With all of that talk about specialized knowledge and trusting institutions that work, we’ve avoided the elephant in the room: medicine.

Guess what? You trust our medical system. You do. You know how I know that? Because you use it.

When you suffer a serious injury, broken bone, heart attack, or stroke, you will be rushed to a hospital. You will let doctors treat you and work to repair you or save your life. You will let them give you anesthetic and do surgery. When you get sick, you see a doctor and take the medicines they prescribe.

I trust our medical system because I have multiple family members (young and old) who would be dead right now without its intervention. I trust it because without it, I probably would have been crippled for life when I badly broke my ankle. I’m sure if you start looking at your own life, and the experiences of your friends and family members, you can find plenty of reasons why you trust it too.

This implicit trust, as with any other industry, is not just in doctors, it is in the entire complex medical system in the background that allows modern medicine to function effectively.

You are trusting the education system that doctors spend years in, you are trusting the basis of the knowledge they gain there, you are trusting in the effectiveness of the rigorous testing and work experience that doctors undergo in training, you are trusting the licensing authorities that certify medical professionals, you are trusting the integrity of the medical research that has been done to find treatments and medicines, the clinical trials that take place to determine the safety and efficacy of said treatments, the regulatory bodies and governmental departments that set the standards and oversee those processes, the hospital governance that assesses risks and sets policy, the management that implements those policies, and the administrators who organize it all.

The cumulative amount of specialized knowledge here is actually astonishing when you think about it. We trust this system with our lives. And with good reason—because we know it works. History has shown us that. Observation shows us that. Data shows us that.

This system that you trust every time you take antibiotics, or give your kids Panadol, or have surgery is the same system that has approved and recommended COVID-19 vaccines.

Maybe you feel distrustful of pharmaceutical companies because they are profit-driven corporations. Fair enough. Luckily we don’t have a system where pharmaceutical companies operate with no oversight and make their own rules and approve and administer their own drugs to us with impunity. We have an incredibly complex, robust, risk-averse system in place, which relies on the collective approval of numerous specialist bodies, consisting of experts with the absolute highest levels of specialized education and experience. Literally every component in that system—the researchers, the educational institutions, the doctors, the hospitals, the regulatory bodies, the medical associations, all of them—are recommending the Covid vaccine.

And it’s not just in Australia (just in case you have decided you just don’t trust our government). Look at the same systems in just about every country in the world. Look at the international bodies of experts whose job it is to research and advise on exactly these kind of circumstances. They’re all in agreement.

If you are someone who feels a little bit unsure about the vaccine, or you’re on the fence, let me encourage you. Listen to the experts. Don’t listen to me, or anyone else on the internet. Don’t listen to unverified sources with no accountability. Listen to ATAGI. Go talk to a general practitioner. Talk to two GPs—or a hundred. Speak to every hospital in your city. See how many of them say the same thing.

Don’t trust memes or YouTube clips or opinion pieces by talking heads. Don’t trust internet “experts” with unverified credentials. Don’t trust sources that bypass the very institutions we have put in place to protect us.

Trust the institutions and systems that have been proven to work.

To the people who are determined not to get the vaccine at all, those who believe there is some nefarious plot afoot: if you honestly don’t trust the entire medical system, stop using it.

I mean it. If you really believe that they don’t have your best interests at heart or if you just think that you know better, then don’t listen to them. If they’re not trustworthy, don’t trust them. Don’t take any medicine. Don’t seek any medical advice or attention. Don’t go to hospitals or get surgeries or treatments. Just don’t. Because it’s the same system, the same institutions, the same people. If you can’t trust their advice about Covid, then you can’t trust them about anything else. Otherwise, you are either being a hypocrite, a coward, or a liar.

At the end of the day, you do have the right to make the choice for yourself. There has never been a drug or medicine in history that is 100 percent safe and risk free. Every one of them comes with some element of risk, however small. Normally that risk is vastly outweighed by the benefits, and dwarfed by the risks posed by the disease they are designed to treat or prevent (and in this case, the data absolutely shows that, very clearly). But it’s still your choice.

But, what I do want to say is that while your choices are yours to make, I would be careful about what you tell others, and particularly about the things you share publicly.

See, one of the things that comes with expertise is accountability.

When researchers conduct trials, when the medical board registers doctors, when immunization authorities approve treatments, when doctors administer those treatments, they are all aware of the consequences. They know that their decisions could literally cost people their lives. And they wear the consequences of that, whether legally, financially, morally, emotionally, or psychologically. Doctors do have to watch patients die. Don’t imagine that they don’t take that seriously, or it doesn’t affect them. They take it home with them at night. They live with it. And it wears on them.

I see a lot of people out there being flippant with the things they share. If you’re sharing advice, opinions, or even memes that contradict the advice of a huge majority of experts, in fields that you are absolutely unqualified to comment on, I would stop for a moment and consider the potential consequences.

When it comes to health, misinformation is literally costing people their lives.

You might not be directly accountable for the things you share in any real world sense. But I’m here to tell you that you are still morally culpable. The hubris to not only think that you know better than the experts who have dedicated their entire lives to something, but to have the baseless confidence to start spouting your opinions publicly, to actively try to influence others on topics you have literally no education in, without a shred of humility to think that you might be wrong, giving no regard for the potential consequences to the vulnerable people you may influence…the sheer reckless arrogance of that takes my breath away.

Your good intentions don’t matter when you’re doing real world harm. There is a point when being factually wrong crosses into being morally wrong. And I’m sorry to say that I see a lot of people, particularly on social media, crossing that line all too frequently.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 22 comments and reply