For 12 centuries in Tibet the buddhadharma taught that compassion and equanimity were what comprised genuine inner wealth, not materialism.

With the Chinese Communist invasion of the 1950s, half the population of Tibet and all but two of its more than 6,000 monasteries were destroyed. Some Tibetans, like the Dalai Lama, managed to escape, but many more were killed trying to escape to India, Nepal and Bhutan or simply starved to death while trying to cross the formidable Himalayas.

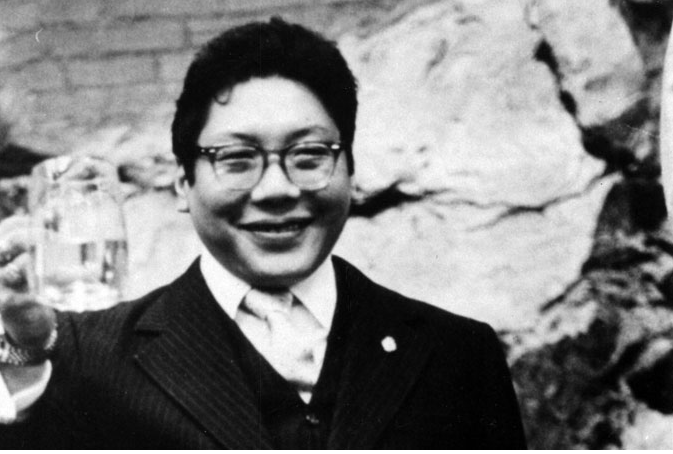

A journey that usually took three months over the highest mountains in the world took Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and his increasing number of followers nine months in 1959. Leaving his homeland later than many others, he and his group had to stop and hide often in order to avoid capture, or worse, by the Chinese soldiers.

The Tibetans who remained in Tibet and who resisted the Chinese were either killed or imprisoned. In spite of prison torture, many Tibetans tried to meditate and engender unbiased compassion for the Chinese, turning austere prison cells or labor camps into intense, retreat-like practice.

But the Chinese invasion took its toll not only on Tibetan culture within Tibet, but beyond in the many Tibetan refugee camps. Tibetans in exile throughout the world soon saw how difficult it was to recreate their previous world in new lands. Almost immediately they had to learn a new language, modernize to some extent, and, unless able to remain monastic, they had to learn to participate in capitalistic society.

Perhaps one of the greatest legacies of Trungpa Rinpoche’s vision was to see that in order to transplant the buddhadharma in the West, he would have to do without much of the cultural trappings and simply teach the essence.

Learning English swiftly himself, he quickly saw the value of translators. Soon he was working with his students who were willing to learn Tibetan in order to translate Tibetan texts into English, while he himself composed in English many liturgies and chants.

Trungpa Rinpoche knew that the true nature of mind, or Buddha Nature, inherent in all sentient beings did not depend upon cultural adornments. He had genuine faith in the experience of meditation and felt his students could tame their minds and then progress to understanding and realization. Monasticism and the Tibetan language and culture were not required.

Even in the West with its constant entertainment and distraction, its speed and aggression, Trungpa Rinpoche felt his students could stop the flow of karma. Or at least put it on “pause,” by meditating daily. He had confidence that meditation could train “the raging elephant” of mind.

But he was famous for saying, “Without ego there is no path,” encouraging students to come as they were. He truly believed that everyone was “workable” and tamable. Although it was the hippy era of the ‘70s, when many young people just wanted to “trip out,” he also resisted promising his students bliss or anything that smacked of what he called “spiritual materialism.” He was very down to earth. As he said, “We begin to realize we don’t have to struggle so much. I wouldn’t exactly call it satisfaction, but breathing space.”

Trungpa Rinpoche encouraged his students to sit, not to get rid of their neurosis, but not to feed it either. The point was to settle rather than struggle, and see what might arise. Whenever we became hopeful about what we might experience he’d smile and say, “No guarantee,” bringing us back to the present moment, breath and sanity. His simple meditation instruction had the effect of dissolving ego, or at least ego’s expectations.

By willing to be so ordinary while still being so brilliant, skillful and a great deal of fun, Rinpoche magnetized hundreds of students. Instead of recommending that they drop out of society, he said, “The path of dharma is unlike the ordinary conception of religion as separate from secular life.”

And each individual was to find this out for his or herself through mixing daily practice with life.

Starting in 1974 with Trungpa’s invitation to the 16th Karmapa, Rinpoche began inviting many of the great teachers of Tibet and we, his students, witnessed how much respect and devotion he had for these teachers. Just seeing His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (who we nicknamed “Mr. Universe”) we felt, really felt, his great warmth and awake radiation.

But Rinpoche also invited many Zen teachers and we were soon to see how much he admired that culture, for soon we too were learning ikebana (flower arranging) and oryoki (an ecological and graceful way to eat food in the shrine room).

Thus as Trungpa Rinpoche taught, he also created what could be called a new cultural container. Shrines were simplified compared to those of his Tibetan heritage. Candles replaced butter lamps; shrine rooms were well lit and less cluttered. And by 1980, as he and certain student-directors were teaching the more secular dharma he called Shambhala, former hippies were now wearing suits and dresses and bowing before entering the shrine room.

Trungpa Rinpoche was interested in everything—in people and politics as well as practice and dharma. He loved to pop our assumptions of what a teacher should be. Because he was so open and had almost no privacy, he was very available and empathetic. Thus we could learn first hand how to be open, curious, appreciative and questioning.

Today, so many of the younger, English speaking Tibetan teachers like Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Ponlop Rinpoche, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, Traleg Rinpoche, and certainly his son Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, have used Trungpa’s phrases, like “spiritual materialism” or “workable,” to resist Westerners’ tendency for goal orientation and self aggrandizement, while at the same time encouraging these students that they don’t have to be Tibetanized to meditate and study dharma.

As Rinpoche said, “The everyday practice is simply to develop a complete acceptance and openness to all situations and emotions. And to all people—experiencing everything totally without reservation and blockages, so that one never withdraws or centralizes onto oneself.”

~

~

~

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Travis May

Photo: WikiCommons

Read 2 comments and reply