I felt like some sort of sicko watching the video.

My eyes took in the despicable play of sadists, and the secret underbelly of a madly lucrative industry that allows for disgusting exploitation. My heart beat low in my gut with every repulsive scene, all of it seeping into my frontal lobe that come nightfall would play again and again in nightmares that circle in on themselves as I tried to sleep.

They were images that I did not want to see, but I knew I had to look at full on in order to confront what lay as a foundational problem of our belt-stretched consumer society.

An hour passes and I am rushing from an American Literature class that I teach at an inner-city college. We had been talking about Anne Hutchinson, that rebel Puritan, and the right to protest that sprang from an inconceivably ironic trial: the Puritans had made a pretty damn intense journey to America in order to set up religion their way and then here sits the minister-governor and his council using sardonically sexist language and bent reasoning on the most intricate theological minutia to condemn one of their own for, yes, exercising her right to religious freedom.

And, oh, the trickster trial. A measure of formality that the religious worship, language that piled up like bricks around the woman as she entered their world of rhetoric, the direct, privileged language of the oligarchy. Turns of phrase and side-speaking that goes a little something like this:

“What exactly am I guilty of, governor?”

“I have just told you.”

“No. You have just been talking, sir. I have yet to hear what I am guilty of.”

“You know exactly what you’re guilty of. You have failed to obey the Fifth Commandment, which says to honor thy father and mother. We are the fathers of the commonwealth and you are in strict defiance of our standards. Surely your parents read the book of Titus to you. You are a woman. You, Mrs. Hutchinson, are not allowed to teach or have authority over men, thence you have failed to obey both thy father and mother and the fathers of thy commonwealth.”

(Just a guess, but there must have been a long, strange pause here.)

“I have only been true to my conscience, sir.”

“It is your conscience then that makes you guilty.”

“Guilty? Again I ask of what, sir?”

Clever, gutsy girl catching a Cambridge educated lawyer in the draw. A death charge built by weightless words. Non-words. The magic of rhetoric, justifying anything, condemning anything, building a case for what has already been decided. Though the words be foolishness, they adhere to the code and we stand like idiots, nodding in agreement over the beauty of the emperor’s invisible clothes.

My students were appalled, slack-jawed as I watched them try to keep up with the tumbling of their thoughts.

“Why the hell would they wanna go and do something like that?”

“I bet it was a conspiracy.”

And then, from an ambitious young man on the front row: “Ms. Ains, it was because she was a woman, wasn’t it?”

Ah. Perhaps. Perhaps the Puritans had more than the blood of the lamb on their sticky hands.

“Is it possible,” I ask, talking over their unabashed exclamations, “to be completely unaware that one is living an ironic life?”

An ironic life. No shit.

Your move, Anne.

The echo of my own question ran like a night train through all that rested shadowed and cool in my mind as I hurried downtown against noon day traffic. I did not have time to think through my circumstances, where I was and more importantly why I was there, until part of me broke away from the whole.

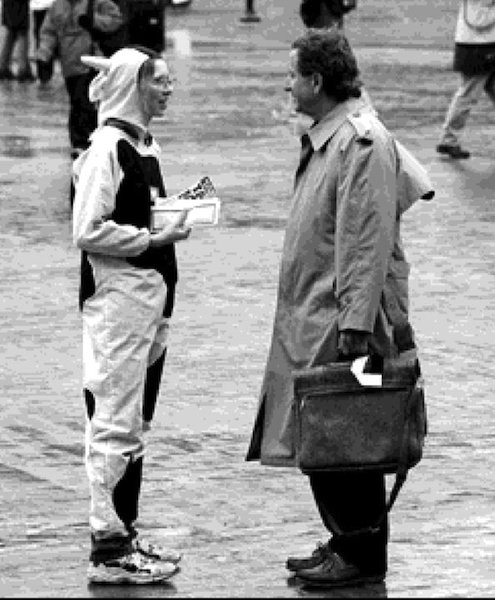

This is the part that knows how to behave in society, the part of me that is above all systematically careful with language and souls. I left her standing quietly across the street watching while the clumsily passionate, thoughtlessly reckless part of me began a riveting, philosophic discussion with a life sized pig, while normal people made wide arcs to avoid us on their lunch breaks.

Facts: Pigs have the mental capacity of three year olds.

—They are more similar to dogs in their attachment to humans, their intelligence, and

“emotion” than any other animal.

—They can learn and respond to their names by the time they are three weeks old.

I knew much of this already, but in a vague, still-eat-bacon sort of way until that sickening video hours before. All I could think as I stared at the footage of grown men torturing caught pigs in a factory a couple hundred miles away was that I would have killed the bastards. I would have flown at them until my rage was through, run ragged, until my sense of impotence and helplessness was soft once more, gaping open, raw like skinned flesh, but at rest in its wounding.

The trouble with this animal rights group is that they were always naked, which was my beef with them (pun intended). They garnered attention to spread their political message any way they could, even if it meant getting stark naked in the middle of intersections, which left me in a moral and political quandary that I planned to address with the event’s organizer. Later.

At the moment I was sweating in the sticky, hard to breathe hotness and attempting to have a conversation with a woman in a life-sized pig costume. Every bit of her was concealed in pink, even her eyes which were checkered with black caged netting. I had to talk very loudly, my voice carrying over the heat stretched air to anyone in range, including the growing group of homeless people sitting on a hill in the park across the street, apparently enjoying the show.

“How long have you been doing this?” I yell into the big pig’s creepy pig-head eye holes.

I hear her say something about lunch, though even that is muffled like her mouth was stuffed with cotton.

“No”, I say, “Not this, I mean how long have you been working with this group?”

I lean closer this time, ear to netted eyes, but her words get trapped again.

“Oh okay. I’m just going to move over here now.”

Perpetual awkwardness.

The Mississippi street sizzles and I tie my hair into a messy braid to get it off my neck as posters and pamphlets are jammed into my hands and I look down to see the graphic nature of the sign I am now clutching. Displayed on a flimsy poster board is a still frame from the slaughterhouse video. The big pig girl (Amanda from L.A., I later learn) held the same grisly poster. Cars slow as drivers gawk, men whistle, and all in all, most do their best to ignore us completely, staring intently down at cell phones, though a few (god bless them) stop and query.

Front and center, my own insecurities come rolling down quicker than I can do a slow inhale, like so many rocks, crushing, each one too much to process with the heaviness of the next, in a constant avalanche that threatens to pin me in my alternate personality spots on either side of the street, a woman split, a woman torn.

The big pig plods away for water, led by a woman named Katie, all tight black skirt and stilettos and tortured pork, with an official t-shirt and name badge, arms full of posters. I re-situate my feet, my shoulders and my hips uncomfortably as car horns honk and bolder eyes of passerbys drift over me, summing, figuring, attempting to type a person who would do such a thing.

Two men walk by in suits, actually make eye contact and smile politely, and I smile back. The big pig turns her creepy block head and stares at me. Dammit, the pamphlets. When the next person passes, a youngish Asian guy who is the same height as me, I shove a pamphlet right in the poor guy’s face.

“What are you guys doing?” he asks, taking the literature cautiously, while looking at me with concern and a hint of a smile.

The big pig is behind me now, satisfied that I am finally doing my job. Her head is off and she is glugging water; her head and shiny wet, tattooed neck is all I ever see of her. The blocky pig head, which has two teardrops spilling from the black hole eyes, is tucked backwards under her arm and the effect is monstrous.

What was I doing here?

“I have no f*cking idea!” is what I want to say. “I watched a video about slaughterhouses right before having to lecture on Anne Hutchinson, and some incredibly weird combination of the two compelled me to drive over here on my lunch break and stand next to a big pig.”

That’s what I meant to say, but instead I heard myself from the regular part of me across the street rattle off in a very precise, utterly professional manner with controlled rhetoric the intricacies of the issue. Pigs are being tortured in a meat packing plant in North Mississippi, which just happens to be in a one million dollar a year contract with the public school system and citizens need to pressure the city to break the contract and demand reform.

Facts are escaping my lips before being processed by my brain, overwhelmed as I was with so much preparatory reading that I have forgotten what I know. As I talk, I nod my head ever so slightly on the big points and begin to see the manipulative language change the emotion in the man’s dark eyes. Language is clay—I can shape it into whatever sharp tool I need, whatever is beneficial to the cause, right? The good of a Puritan colony, the good of animals, the “good” of Hitler’s Germany or of war time propaganda.

Words drip deadly. I can make a perfect stranger care about pigs in a rural, nondescript, backwoods county three hours away in the heat-slated, hate burgeoning state of Mississippi. The skill rises unconsciously from some place deeper than owning, a lifetime of watching, maybe, and a metaphorical knowledge of steel bars.

The more I talk, cornering the poor man, the angrier I become. Images flood like overrun creek beds and clean swept caves of years, scuttling like spiders from the past, their gossamer webs connecting too many things at once: screams of trapped pigs at the mercy of man, boys grown up crippled in the conscience, ever with something to prove, my own childhood sexual assault, unblinking denial of clergy positions in a church because I am the second Eve, that first slut-temptress, created for babies and stoves, Anne Hutchinson’s murder first by the Puritans and then by the Indians, a culture that says “no” is a cunning rape-lie word and here’s some pepper spray just in case, eyes that follow too closely, even now on the hell-hot street, penetrating the illusory wall between flirtation and aggression.

When I finish my spill, my intensity frightening myself even more so than the poor Asian guy, whose eyes have grown big, I realize that the high-heeled blonde is now standing in for the pig, who is a pile of pink on the Education Building lawn. “I’m melting,” she had said to me, but when someone earlier asked her how she stood it, she said through her netted mouth (and I translated), “It’s nothing compared to what the pigs go through.” Repeating the words, I grimaced at the statement which sounded canned no matter who said it.

The blonde, Katie, Campaign Manager, glances at me approvingly, summing me up the same way I had summed her up. I had never been to one of these shindigs because the last time this group barreled into Jackson, Mississippi, they caused quite a stir. Shower stalls were set up in the middle of a crowded street and women, naked but for a barely there curtain, pretended to shower. “It’s for a good cause,” they had said.

I find this as equally repulsive as what is being done to the animals caught in the capitalist scheme that is America—flesh as commodity. Now that I have Katie to myself, I question her, interrupted of course every few minutes by passers-by, who were given a pamphlet and a run-down of the issue even if they continued walking, even if they put a defensive hand in your face. The game was to keep walking with them, keep talking until you were through, no matter how dismissive the person was. Animal welfare proselytes. F*cking proselytes, we were.

I cautiously ask about the shower stunt. “So how did all that get started?”

“It’s amazing,” she says. “You can stand around with posters and pamphlets all damn day and no one notices you, but you put six naked women in a fake shower and people will knock themselves down to get to you.”

She tells me about her first time at a convention. No one was stopping at their booth, which was plastered with photos of tortured animals, leaked videos playing on a big screen with brochures with ghastly pictures plastered across the front of them stacked in neat rows. The “shower” was some kind of slaughterhouse floor reproduction. No one was interested.

“So I just took off my clothes and hopped in,” she goes. “Of course, I wasn’t really naked. I had on a strapless bra and panties, but you couldn’t tell from looking.”

I immediately admire her gall, but the more she talks, the less I respect it. The booth was crowded in minutes and she had lots of “meaningful conversations” with people (mostly men I can only assume). A slaughterhouse turned live porno. Naked women with bare feet where a bloodbath was meant to flow. An easy swap out of women for pigs and cows.

The only other time the group came to our city, there was a car wash. Women in lettuce leaf bikinis washed cars at a gas station and fully clothed protesters waved signs about the abuse incurred by the animals that were a part of a traveling circus that had pitched its tent at the fairgrounds. Another large crowd and lots of publicity.

But at what cost?

Now women were wearing food and washing cars, consumable, serviceable.

Put them naked in slaughterhouses. Clothe them in food, lettuce-wrapped breasts and c*nts, use one form of oppression to lobby against another.

Your move, Katie.

I am desperately trying to keep close guard over my tone. “Your campaigns take some flak for being sexist at times, huh? What do you think about sexism as a stand-in for animal rights? I wonder if we could be swapping one oppression for another. Dr. King has this great quote that basically says if any living thing is exploited, all living things are exploited.”

In a mounting minute by minute fear of sounding like the Buddha, when it was her turn, I nodded my head ever so coolly throughout her responsive diatribe, that stacked jargon, affirming her reasoning with quiet yeses and uhuhs, all the while my mind screamed, “Excuse, girl! You’re making excuses!”

“Sex sells,” she goes. “It’s for the good of the animals,” she says. Blah, blah, blah. She knows The Sexual Politics of Meat, the feminist-vegan bible. She is highly intelligent and even commiserating with my concerns, while explaining how she regularly play-showers naked on city sidewalks to attract (male) attention and have “meaningful conversations” with people (um, men) about the exploitation of animals.

Again I should say that I have immense respect for Katie and the work she has given her life over to and I am bound to her in the same way women are perpetually bound to tortured and suffering animals. I am tied to her for the same reason I felt the need to stand on a busy street of my city clutching a poster emblazoned with images of nightmare cruelty, animals shocked to pieces and then butchered for Saturday morning bacon that sizzles fatly in skillets all across a history-stuck South.

But someone needs to answer for what is being done, dammit.

All through arguing politely with Katie, yelling questions to the big pig, and invading the personal space of lunch break strangers, the video that made bile rush to the back of my throat like a choking chain plays on repeat in my mind—god, those metal barred death traps, evidence once again of man’s fallen state, his constant need for domination and black-hearted cruelty. The animal has no possibility of rushing forward or backward in its cage, no way to escape the seizure at the end of an electric prodder.

A sow, a mother.

Her babies tossed very much alive and starving into a trash compacter, their mewing eerily similar to my own infant’s middle-of-the-night hunger cries. The babies are shredded to screaming bits, the mother still in close vicinity to the crime scene. The men prod the sow again and again, sending her into spasms only to struggle wearily to her feet and be stunned again, continuously, for 30 minutes straight. You can hear the men’s laughter over the zing of the electric prod, sadistic and unchallenged. She bashes her head against the thick bars because instinct does not easily recognize entrapment and always says run.

The cage is opened.

She is dragged to the kill floor and jerked violently into the air six feet above the ground by a thick chain, screaming, screaming, screaming. There is no electric paralysis this time, which is the stun gun’s only purposed function. Her throat is cut and her panicked squeals continue as her blood spills onto the already soaked concrete, splashing up against the men, splattering them with remnants of spent life.

So much blood on our hands.

Play showers and prostitute-proselytes.

The endless rape that is factory farming.

The violence on our plates, violence ingested, keeping us alive by harrowing death.

For the majority of my life I have been a carnivore. For the majority of my life I have refused to look at the blinding contradictions, the paradoxical verbiage that makes for quick-sand walking in a society that stays alive through the torture of living creatures and still, in f*cking 2014, sees women as bodies deconstructed for the basest form of male gratification: legs, breasts and thighs on the butcher block of culture.

My own question hits me headlong, demanding an answer: “Is it possible, students, to live an entirely ironic life?”

I am sweaty and exhausted by the time I make it back to campus. “You look like shit, Ms. Ains,” says a member of my 2:00 writing class. Thanks. I’ve been a little too emotionally unhinged to think about my hair, but I appreciate you pointing that out, honey.

You look. That’s still the problem, right?

“How many of you know where your meat comes from?” I say from the front of the classroom, wilted and all full of spent fury and indignation, feeling caught in the net of rhetoric, realizing that we have to use a wrong code to reason for the right one like voiceless little girls in big pink costumes.

“Um, Walmart?”

Smart ass.

I smile ever so slightly. “Let me tell you where I’ve been this afternoon, about pigs, and about a Puritan woman.”

Anne Hutchinson, a woman disposed of by men, a voice alone in a murderous wilderness that would soon become a nation of violence against the most caged of creatures.

She knew that they were accusing her of was true: she was meeting authority with authority and she did not have the dick for it.

“You know what you are guilty of,” says Winthrop.

So do I, I’m afraid. Sex rules and church rules and, for us, blind consumption of ignorance. An ironic life.

“I have been guilty of wrong thinking,” says Anne, swallowing the hard bones of those words, I’m sure, voice trailing, maybe. . . .

The judgment: “You are banished from our jurisdiction for being a woman not fit for our society.”

Yes. Irony upon irony that has built a word-house culture of high heels and tortured pork, a culture of sex and slaughter.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Travis May

Photo: Provided by editor with permission

Read 1 comment and reply