What do you do when you get anxious?

When your “anxiety spot” gets too big, how do you handle it?

How do your kids handle it, and did you know it’s normal to feel anxiety?

It’s become such a commonplace label in society that we have started to self-identify with it—as if it’s abnormal—losing sight of our whole and complete essence, which allows us to experience all emotions without judgment.

Trouble comes when anxiety starts to impact our everyday, regular life negatively in a chronic fashion.

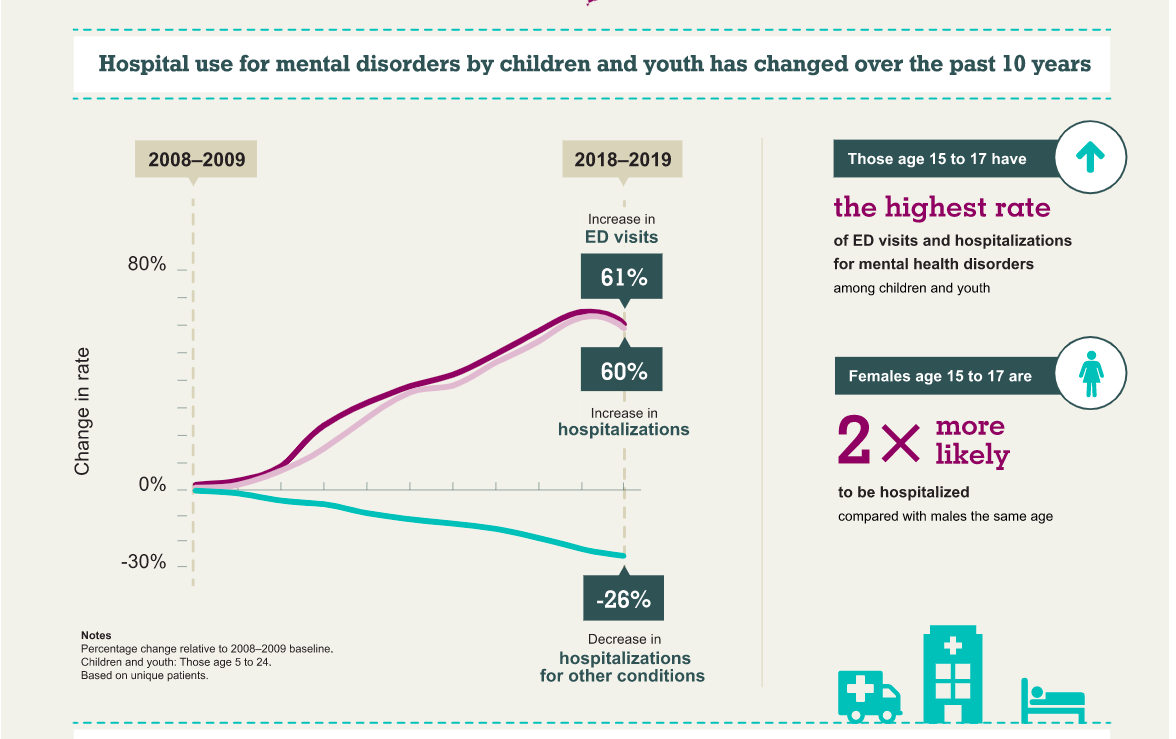

Kids are now more anxious than ever before—one in 11 kids were dispensed mood or anxiety medications in 2018-2019.

After a pandemic, would you say that’s gone up or down? You and I both know the answer to that question. Anxiety is a secondary emotion; it’s often a combination of a few of the primary emotions. Anxiety, in most medical and psychological studies, is strongly correlated with fear: fear is often the primary root emotion.

It makes sense to me why kids might be feeling so much anxiety. Life isn’t the same as it was when we were kids.

Things are a lot more complicated now. What a 14-year-old child experienced 20 years ago is what a 9-year-old child has to manage today.

Kids have more anxiety about more things, and today’s “gotta have it” and “gotta do it” attitude is contributing to it:

Gotta’ have the latest app, technological gadget, and toys.

Gotta’ do all the activities so my child gets a “well-rounded” life experience.

Gotta’ have high grades.

Gotta’ do well in school, dance, soccer, baseball, piano, and martial arts.

Gotta’ do what my parents say. Gotta’ behave with the grandparents.

Gotta’ be on TikTok, or no one will think I’m cool. Gotta’ fit in.

Gotta’ be brave. Gotta’ hide my fears. Gotta’ get all the right answers and not screw up.

We are quick to post our kids’ gold medals, certificates, and awards, on social media—but not their mistakes.

Statistics show that kids are being exposed to bullying, sex, drugs, and alcohol at younger and younger ages. They are being strongly influenced by media, as more kids increase their screen time.

Plus expectations.

We used to live in close villages where everyone helped one another with kids, business, and family. Now we live in far more isolation, and parents are still expected to do it all without a single hiccup.

Because of the many expectations of parents, it’s easy—and quite unconscious—to pass those expectations on to our kids by osmosis. We expect them to “pull their weight”—even if their mind-body system isn’t ready to handle the never-ending list of expectations.

Can you imagine the impact on your nervous system with all this weighing on it?

How about mistakes or forgetfulness? I have been working with kids for 21 years, and one of the hardest obstacles to overcome as an educator and coach is a child’s fear of making mistakes.

My fellow parent coaches and I call the “power-over” style of parenting, which is when mistakes are punished; this also extends to teachers and caregivers.

A reward and punishment system where if you don’t make a mistake, you get a sticker. If you do make a mistake, you get a negative comment written in red pen on your report (remember those days?).

I remember being in first grade, a tender 6-year-old girl, when our teacher used to snap her wooden meter stick on the desk when she felt irritated with a child’s mistakes, or her perceived incompetence of the child—it scared me.

This isn’t the norm in schools anymore, but there is definitely a “command and obey” stance in the “power-over” patterns that society still follows. In fact, it’s so ingrained in us, it can be our default patterns—even for the most conscious parent.

It’s not all our fault.

We’ve picked up this way of parenting and leading children through intergenerational patterns. We’ve learned this behavior from our parents and their ancestors and genetically inherited these behavior patterns as well.

And it’s hard to overcome without deep realization, knowledge, self-awareness, guidance, leadership, and education around the long-term impacts on a child’s psyche.

What emotion does the “punishment and consequences for mistakes” style of parenting lead our kids toward? Fear. Fear of making mistakes. Fear of upsetting other people. Fear of judgment. Fear of being hurt (emotionally or physically).

And then, what does fear lead to?

Anxiety. When we don’t want to get it wrong, but we’re worried we may.

It also leads to perfectionist tendencies. We don’t create confidence, nor do we create healthy self-esteem when a load of expectations, punishing mistakes, and the “gotta have it” and “gotta do it” patterns prevail.

In Diane Alber’s new book for kids, A little Scribble Spot, all the characters draw their emotions, but the character called, Anxiety Spot, doesn’t draw anything. He’s afraid it won’t look good, and so the anxiety remains inside him—it’s not released.

Phew. Heavy, huh? Trauma comes in all shapes and sizes.

I am glad to be a Trauma-Informed Coach and facilitator with training and certifications under my belt, plus always undergoing further training. I love learning about the human psyche.

Some people think trauma is just the big stuff that happens to you, but trauma exists in little things too.

I’m currently studying with Irene Lyon, one of North America’s leaders in nervous system health.

Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk, a trauma specialist, indicates that “none of us have escaped trauma.”

The child’s brain and mind-body system don’t fully mature until age 25 or older. Their system is not equipped to handle chronic levels of anxiety, fear, and stress (actually, nobody’s nervous system, adult or child, can manage chronic anxiety, fear, or stress without intervention). Our life experiences shape the neural circuitry in our brain. When certain patterns are repeated, the neural circuits for those patterns are strengthened and eventually become our child’s default patterns.

On the surface, as a fully grown adult, it may not seem like our child has a lot to navigate or deal with, but I would gently request of you to put on your “kid goggles.”

Can you see the world from their immature eyes? Can you imagine being in their mind and body?

Plus, in the middle of a pandemic, the bylaws and restrictions constantly changing: social isolation and basic things, like birthday parties being canceled.

Adults are quick to say that kids are resilient. I’d like to shift that sentence for you: kids can be resilient if they have tools, resources, and strategies in their pockets to deal with what life hands them.

My husband has said kids are resilient a lot, yet he only discovered his own trauma from his parent’s divorce at age 10 a couple of years ago. He realized after getting some help that it caused him to shut down emotionally for the majority of his adult life; this impacted his ability to connect with me on an emotional level in our marriage.

But that stuff happened when he was 10 years old. Kids can be resilient because their brains are more pliable, and they can learn skills for resilience quickly. But they won’t naturally do this without knowing how to. The challenge is that most adults don’t know this stuff, and I get to teach it to kids.

I feel for the kids of the world, and I am with you, parents. We can make choices to help ourselves and our kids. We just might be needing some support on how to do that.

Increase both your own and your child’s emotional intelligence.

Garner the ability to notice and name your feeling. Diane Alber’s book, A Little Scribble Spot, is a lovely resource. I love this book. It’s great for little kids, but you can read it together with kids as old as age 11, and then have a family discussion and make some scribbles of your own.

Reach for help and support.

All of us come into our parenting journey with a lifetime of our own stuff, and sometimes this stuff shows up in unexpected ways. Sometimes it shows up in ways we don’t even realize.

Here are a couple of examples of how it shows up unexpectedly:

I coached a set of parents in 2020 who realized how strong their limiting belief of “not have enough while growing up” was creating patterns in the family dynamic that disempowered their child.

When the child completely ignored any parental or family boundaries, the child was punished. The parent guilt followed and fed more into a disempowering dynamic. It was a cycle that fed itself. The child was also experiencing anxiety amidst all of this.

I coached a parent who told me he “didn’t do vulnerability.” By holding this limiting belief, he found himself in a loop of taking on his child’s challenges emotionally and driving that energy deeper into himself, and shutting down.

Again, a cycle that fed itself.

The vulnerability would help release emotional energy, but his relationship to his trauma held him back.

He lived in anxiety each day and prepared himself for his child’s arrival home as a potential onslaught of what might have gone wrong that day. This anxiety is then transferred to his child.

Coaches like myself are working hard to empower families, and your family can be one of them.

There is hope. There are helpful ways to resolve the dynamics that impact our kids today.

Read 2 comments and reply