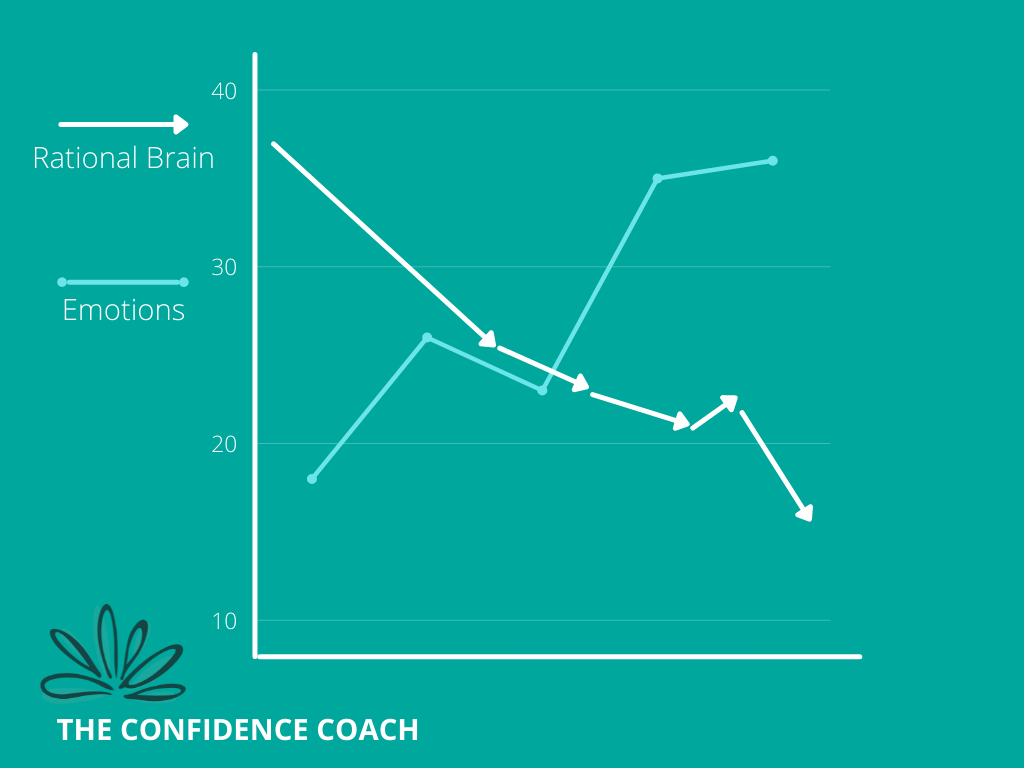

“When emotions go up, intelligence goes down.” Dr. Justin Coulson recently said this.

I’ve heard people before him say it, but I recently heard it from him.

Before you freak out, let’s put some context to this.

Now he’s not saying emotions are bad. He’s not saying don’t feel your feelings.

He’s talking about the physical response in the body that happens when our emotions get really high—specifically, flipping our lid (anger), but also in high levels of anxiety. I have also witnessed that in depths of sadness, we may also stop seeing possibilities even if possibilities lay in plain sight—all thanks to how our brain-body system works.

So by saying when emotions go up, intelligence goes down, he’s not saying we’re not intelligent. Simply the fact that we are human gives us great capacity to learn, grow, and develop our mind-body system—a bonus that other animals on our planet don’t have.

He’s talking about what happens to our mind-body system during heightened emotions.

We know from research and nervous system science that when emotions are going up, particularly anger (which many parents experience throughout their daily lives), our ability to make rational choices goes down because our nervous system is being activated.

Something that is commonly spoken about amongst parenting coaches, like myself, is how our kids can pull every trigger we have. They don’t mean to do it; we just have those triggers within us already. A common response to many triggers is anger.

“Anger can be one of the most difficult emotions to work with.” ~ NICABM

Anger can impact how the amygdala in the brain—the organ that tries to protect you from danger—responds. Anger is a reactive response to some stimulus, and the amygdala goes “Uh-oh! Wtf! Something’s not right here,” and thereby a cascade of physiological responses happen in the body, including blood flow moving away from key areas, such as digestion and certain parts of the brain, toward large muscle groups to prepare the body to “flight or fight”—to prepare the body to move.

Hence, one of my coaches said to me during my training with her, “Anger lives in the arms.” Our limbs want to move; we may have the urge to throw something (I have broken at least three cell phones doing this *insert facepalm emoji here*), or unfortunately end up on more violent paths. Our legs are impacted too; we may stomp, kick, pace back and forth, or want to walk out on someone who we perceive is the source of the anger stimulus, or we may have some other urge in our legs.

(On a sidenote, does any of this remind you of your children? Oh, so they are normal. Who would’ve thunk it! Just kidding—or not.)

Here are some steps to consider in helping ourselves as parents who experience anger:

Understand how anger works in the body and accept all your emotions. If we resist our own humanness, for example the fact that we got mad when we shouldn’t have, resist being sad and put on false bravery, and go into self-diminishment habits such as negative self-talk, self-neglect, or self-harm, we unfortunately feed the cycle—because our mind-body system doesn’t like to have this imbalance of self-love or self-acceptance.

Our mind-body system prefers homeostasis. And although the world “hormonal” has gotten a bad rep lately, we are actually hormonal beings! Our hormones direct our impulses. So, when stress hormones go up and other parts of our biology are impacted, we aren’t in homeostasis.

Acceptance, on the other hand, is one piece of the puzzle of human life. Some experts say “name it to tame it.” And that is an incredible act of acceptance. Because the opposite is resistance, or worse, suppression.

Just stating aloud “I am very angry right now” can allow some level of acknowledgement and release.

Trauma plays a role here; if we were taught as young children that our “negative emotions” are bad—not to be experienced and not to be displayed, and thereby not accepted by our parents or caregivers—we would have learned to release these emotions in other ways that might not have been beneficial or may have even be harmful. Or we would have learned to suppress. This is a type of trauma.

Understand that many of our “negative” emotional responses are a result of unmet needs. A chronic pattern of unmet needs—usually a bulk of which occurred in childhood and repeated throughout our lives—creates trauma. Trauma is not just a car accident, large catastrophe, or sudden deaths or losses.

Trauma comes in many shapes and sizes. And today, adults who are walking and talking around us are often carrying unresolved trauma. This means our trauma responses are still active as well.

There have been many a time when I was triggered by my husband and was later (when my brain was more rational) able to trace it back to a root source from childhood. Doing this kind of work to be able to trace back such responses takes a lot of that “inner work” coaches and therapists often refer to. And it always takes a support person to do this inner work with you. I’ll always remember this quote from Les Brown, “You can’t see the picture when you’re in the frame.” (Love it!)

Practice emotional intelligence and noticing body sensations. Learning how to notice, feel, sink into the body, and name feelings and sensations is important. Learning to pinpoint your emotions as they arise is really helpful. I would even call it a practice of self-acceptance.

What’s interesting as you start to dive further into self-awareness of your feelings and sensations is that you’re able to witness your emotions and not act on them—which is a delightful place to get to. You can just name it. Nothing else needs to happen.

“I’m feeling sad.”

Period.

No fixing. No “should-ing.” No changing the feeling to something different.

Often allowing ourselves to feel our feelings allows the feeling to come and then gently dissipate too. Imagine a friend sitting beside you. You tell them you’re sad. And they don’t say anything. They simply squeeze your hand and give you a kind and loving nod of acknowledgement. Something that says, “I get it. I’m here.”

Now we’ve walked into something called “self-empathy.”

Practice self-empathy. Self-empathy is a life skill—one most of us didn’t acquire. Sometimes self-empathy is referred to as self-compassion. It’s realizing and allowing that something is really truly hard to experience, or sad to experience. And that the experience that is being had is okay.

I often offer to my clients the chance for compassionate self-touch when offering them self-empathy. When asking clients to be gentle with themselves, I offer them to use their hands to show self-affection: maybe a hand to the heart, hand to the belly, hand to face, or downward strokes of the arms in a self-hug position.

Anger may reside in the limbs, but love lives here too.

That’s why we crave touch and hugs as humans. It’s part of our primary survival mechanism as children: the social engagement system. But as we grew, many of us didn’t get our needs met for loving attuned affection or physical affection from our parents or caregivers. This is starkly apparent when you consider the mask of masculinity wherein many fathers refrained from showing affection to their sons in the aim of “toughening them up” for life—which we now know has backfired.

Kids depend on physical affection, and when fathers can give this to their sons (in addition to mothers), it allows for a balanced childhood of compassion and resilience. Because when your “cup is full,” it’s easier to bounce back from setbacks (resilience). But many boys/men were running on empty…and that emptiness (well, that’s another blog post) results in other types of dysfunctions, such as inability to handle rejection from an intimate partner or demanding touch or seeking touch inappropriately.

So, back on topic now: self-empathy and compassionate self-touch are important for improving how we respond with our children and how we parent them. We can be a catalyst for positive intergenerational change if we consciously step into becoming the “Conscious, Confident, and Empowered Family Leaders” that we know we can be—knowing that we have never had as much information about the human brain and mind-body system as we do today.

Self-regulation. Self-regulation is also a skill. But once again, due to intergenerational parenting patterns, many of us didn’t effectively learn this without denying some aspect of ourselves. Self-regulation as children starts as co-regulation.

Because the child’s brain doesn’t fully mature until age 25+, that brain is more impulsive in nature, reactive, and doesn’t always logically process choices and consequences like a mature brain can. Thus, self-regulation in children begins with co-regulation from an attuned caregiver who themselves can self-regulate well.

By the way, I didn’t learn any of this until I was in my 30s. I didn’t even know what self-regulation and co-regulation were. So please practice self-empathy here for not knowing.

There are many ways to self-regulate, but the key component to understand here is that this is not just mindset or changing thoughts, but integrating nervous system understanding and healing. When you self-regulate, you consciously practice techniques that allow your nervous system to come back to a more balanced state.

Many people use breath work, conscious movement, following impulsive movements, somatic therapy, self-expression including emotional release techniques, such as a rage page, pillow-bashing, or other aggression release. Others integrate meditation and mindfulness, EFT, and so on.

What I personally don’t like about traditional mindfulness and meditation as a tool is that it may not promote the release of negative feelings, but it can promote regulation, or at least provide a nervous system “break” after episodes. So don’t misconstrue that because you’re angry you need to meditate. It’s actually the other way around: you meditate because you may get angry sometimes.

The act of gently caring for our nervous system through a meditative practice, or other mind-body practices or somatic healing, can allow our nervous system the opportunity for more balance. When more balanced, over time, and with regular practice, we may find our self-regulation increasing.

Now, I’m not saying go meditate and your problems will be solved. There’s more to it than that.

But let’s save the rest for another day.

Sending you love and light,

Ashley Anjlien Kumar,

The Confidence Coach.

~

Read 2 comments and reply