In 1961, “Charlotte’s Web” author E. B. White wrote a blunt letter to a young girl wondering about his next children’s book:

“I would like to write another book for children but I spend all my spare time just answering the letters I get from children about the books I have already written,” he wrote.

“Letters now come to me faster than I can answer them,” he continued in a letter to her indignant librarian. “So in the long run, although I’m not immune to praise and to friendliness, I get impatient with the morning mail, because it is, in a sense, my enemy—the thing that stands between me and a final burst of creative effort.”

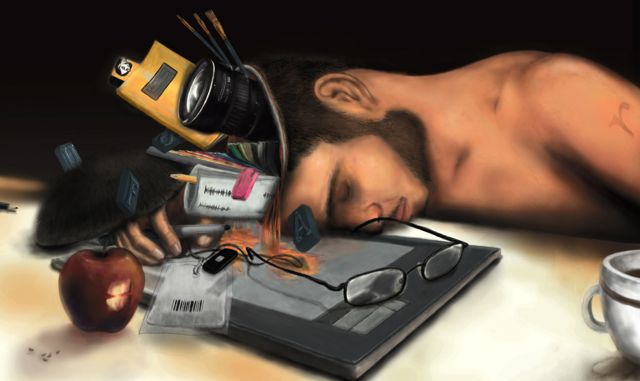

It’s a common refrain among popular writers: it’s impossible to respond to the volume of incoming communications and still have time to do their work. With modern technology, it’s not only the emails, messages, calls and Twitter replies (and maybe even a couple letters) that overwhelm, it’s all the notifications announcing each new missive.

One doesn’t have to stop typing, get out of his or her chair, and walk to the mailbox for an excuse to avoid working, one simply has to look at a digital counter (carefully designed to be obtrusive), or glance at a smartphone, or simply wait for a buzz or a ding.

And there are plenty of messages to turn to even for those of us who aren’t so popular. A million sites on the internet are always sending out info asking for a reply, or at the very least a few moments of attention. Those moments add up and the work never gets done.

The phone rings and our email dings. The mind clings. And the muse takes wing, looking for someone who will pay attention when she sings.

It’s up to us to manage our energy, creative and otherwise—physical energy, mental energy, emotional energy, energy to focus, and so on, divided into as many categories as one wants. Together, they’re the indefinable and crucial ingredient we have to give to our work, the spark for expression, the oxygen we breathe into the always burning fire of creation.

Some energy drains are unavoidable. But most of the time, we’re simply giving creative energy away, making ourselves available to be snatched by every opportunity for entertainment, for distraction, for forgetting.

Responding to modern mail is certainly less labor intensive than it was for E.B. White, who in responding to requests often had to mail books, which meant he “must find the wrapping paper, the string, the energy, the right amount of stamps, and take the parcel to the post office up the road. This can occupy a whole morning, and often does.”

Yet I can still quite easily spend the whole morning responding to information instead of doing my work.

In Carlos Castaneda’s Journey to Ixtlan: The Lessons of Don Juan, the story of his ostensible conversations, confrontations and re-education with Yaqui Indian “sorcerer” don Juan Matus, he shares don Juan’s lesson about “being inaccessible.”

“You must learn to become deliberately available and unavailable,” don Juan tells him, “As your life goes now, you are unwittingly available at all times.”

Don Juan clarifies that this does not mean removing oneself from the world, hiding or being secretive. It’s a matter of how we use the world, and how we allow ourselves to be used.

Don Juan continues: “You must retrieve yourself from the middle of a trafficked way. Your whole being is there, thus it is of no use to hide; you would only imagine that you are hidden. Being in the middle of the road means that everyone passing by watches your comings and goings.”

It’s fitting that we call internet data “traffic.” Staying focused on the internet often feels like playing a game of Frogger. Physically and digitally, we throw ourselves into everyone else’s faces, and expect to maintain our autonomy. Our comings and goings become fodder for our online identity, while we beg to be watched.

“We are fools, all of us, and you cannot be different,” don Juan tells Castaneda. “At one time in my life I, like you, made myself available over and over again until there was nothing of me left for anything except perhaps crying. And that I did, just like yourself.”

The principle of being available and unavailable has vast implications, but even the simplest elements we accept as necessary can keep us “unwittingly available at all times,” standing in “the middle of a trafficked way.”

A phone that we turn to with every notification, email we check with resigned piety, websites and social networks that own us—our attention, our connections, our fabricated identities—as much as we own our role in them. We give ourselves with abandon for fleeting and fickle attention and recognition.

Other people’s unwarranted demands on our time need not be our primary concern. That message, that email, that phone call, that notification can wait. Each is a choice, and each time we can choose differently.

As Patrick Rhone puts it, “Saying no is simply saying yes to other things.”

Don Juan brings up a woman Castaneda used to be with, until she left. “You lost her because you were accessible; you were always within her reach and your life was a routine one,” he says.

“You’re wrong,” Castaneda retorts. “My life was never a routine.”

“It was and it is a routine,” don Juan says. “It is an unusual routine and that gives you the impression that it is not a routine, but I assure you it is.”

“The art of a hunter is to become inaccessible,” he continues, “In the case of that blond girl it would’ve meant that you had to become a hunter and meet her sparingly. Not the way you did. You stayed with her day after day, until the only feeling that remained was boredom.”

How many memes, viral trends and celebrities have been forgotten, siphoned of any interest by incessant focus and repetition? Then there are legends like Bob Dylan, famous for the shroud that surrounds him, yet generous to his music, his life’s work, giving himself to the performance on countless tours. He is available on his terms.

An unnamed friend of his told Tom Junod in Esquire, “He does a lot of walking no one would expect. He’ll walk through neighborhoods undetected and talk to people on their front porches. It’s the only freedom Bob Dylan has—the freedom to move around mysteriously.”

Even after the example of “that blond girl,” Castaneda is unconvinced that’s he too available. “To be unavailable means that you deliberately avoid exhausting yourself and others,” don Juan says. They converse until his meaning is clear:

“ ‘ A hunter knows he will lure game into his traps over and over again, so he doesn’t worry. To worry is to become accessible, unwittingly accessible. And once you worry you cling to anything out of desperation; and once you cling you are bound to get exhausted or to exhaust whoever or whatever you are clinging to.’

I told him that in my day-to-day life it was inconceivable to be inaccessible. My point was that in order to function I had to be within reach of everyone that had something to do with me.

‘I’ve told you already that to be inaccessible does not mean to hide or to be secretive,’ he said calmly. ‘It doesn’t mean that you cannot deal with people either. A hunter uses his world sparingly and with tenderness, regardless of whether the world might be things, or plants, or animal, or people, or power. A hunter deals intimately with his world and yet he is inaccessible to that same world.’

‘That’s a contradiction,’ I said. ‘He cannot be inaccessible if he is there in his world, hour after hour, day after day.’

‘You did not understand,’ don Juan said patiently. ‘He is inaccessible because he’s not squeezing his world out of shape. He taps it lightly, stays for as long as he needs to, and then swiftly moves away leaving hardly a mark.’ ”

I can see, in my use of technology and elsewhere in my life, that I make myself unintentionally available. I exhaust myself with distraction, wasting the energy I could instead be directing into something worthwhile. And I’ll include others in my distraction with needless sharing, the equivalent of carving my name into hard stone on a well-traveled trail, promoting my identity instead of creating something actually worth remembering.

It’s something to consider the next time I do (or don’t do) anything—even something as simple as sharing a link.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Apprentice Editor: Dana Gornall/Editor: Rachel Nussbaum

Photo Credit: Flickr/Dylan Roscover

Read 1 comment and reply