Relephant read: Elephant’s Continually updated Coronavirus Diary. ~ Waylon

I’m in the front yard with the dog.

Sunshine drips down through an unbothered sky. Tangles of grass begin to green after a long and dormant winter. I bask in this pocket of peace. The thought maybe everything is okay floats through my mind.

~

I’m lying on my mat during a Zoom yoga class. It’s the end of a day that feels like a week, and my bones sink into the floor, supported. The clenched muscles in my neck and shoulder begin to release, and I hear the hiss of my own sigh.

A moment later, I’m crying and shaking. A hint of my dad’s presence swims through me; I’ve only felt him near a few times since he died last June.

Billions of lives have been disrupted with the pandemic, and yet my grief for my dad has its own life force, its own shudder and heft.

What would he make of all this? I wonder.

I’ll never know the answer.

~

My kids are scattered across our bed like starfish while I read to them. We haven’t read stories together as a family since we binge-read most of the Harry Potter books a few years ago. It’s a sweet ritual to return to. My children’s bodies have lengthened since the Harry Potter days, claiming more space. The dog’s eyes flicker and close, her chin nestled on my son’s shoulder. I am wrapped in family.

Thank you, I whisper to the universe. I close my eyes and inhale, preserving a mental snapshot to save for later this afternoon, or in five minutes, when the kids begin bickering and the dog whines and I want nothing more than to be alone, to be untethered.

~

I’m sobbing into my pillow. A ticker tape of shame runs through my mind: I have no idea how to homeschool my kids. I don’t even know how to put together a simple daily schedule. I have the executive function skills of a spider monkey—my kids deserve a better mom. I can’t do this, I can’t do this, I can’t do this.

I can’t do this, and yet I have to do this.

~

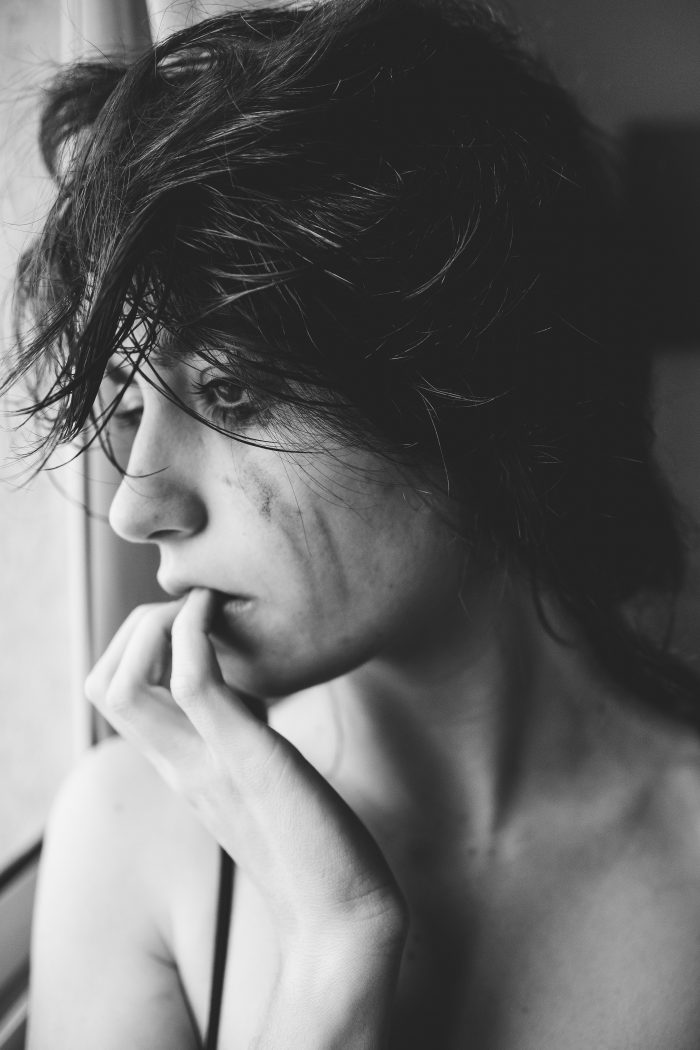

This deep unsettling, this barrage of ever-changing emotions, is so familiar. The snapping awake, over and over again, to the awareness that the bottom has dropped out of our lives. That the landscape is suddenly and startlingly different, and no one knows if or when we’ll return to more familiar vistas.

This is grief.

I recognized it before I read the wise articles that affirmed that we are in the midst of a worldwide collective grief. Since my brother died 21 years ago, bisecting my life crisply into before and after, grief has been a close companion. I’ve spent years hunting for words to describe the precise ache in my sternum, or how long and craggy the road to acceptance is, or how we must dismantle the murky myths that grief is something to fix or crawl around or reach “closure.”

Now, we grieve together.

We grieve that our lives as we knew them only a month ago have sharply shifted. We grieve the lives lost and the lives that will be lost. The vanished jobs and routines. We grieve that our government failed to protect us. We grieve the oceanic uncertainty, the outrageous inconvenience of it all.

Who stole my protective bubble?

Perhaps most deeply, we grieve the layer of protective tissue that’s been ripped away, proving that bizarre and terrible things can happen—a deadly virus can hop from a bat to a human, unleashing a worldwide pandemic. When my brother died, I mourned so much: the loss of the co-keeper of our childhood, the promising rumblings of an adult friendship, and the decades of future I’d assumed we’d have, brimming with holiday gatherings peppered with the raunchy jokes we both favored, the sweet and unassembled faces of nieces and nephews I can only daydream of.

But besides the longing for my singular brother, for the previously unappreciated, suddenly sacred role of sister, his death also jolted my sense of security in the world, the bubble I hadn’t known I resided in, the relics of fairytale endings I didn’t realize I’d relied on.

The yo-yo of grief.

Grief is messy and muscular and non-linear. We zigzag from anger to denial to depression, with strange respites of feeling absolutely fine.

Last week, I realized I needed a project. My new—and yes, quite unwelcome roles of a home-schooler and a constant snack provider were too amorphous. I craved the ability to accomplish something—anything, that possessed a beginning, a middle, and an end in this infernal loop of Groundhog Days. So I decided to clean out our garage and shed. I paced between the yard and shed and garage, scanning for half-deflated footballs, shards of plastic, slabs of irrelevant stereo equipment. In the driveway, I assembled a small mountain of rusting, outgrown tricycles, cracked shovels and mouse-nibbled box springs.

When the garbage removal service came and hauled the trash away, I was downright giddy—the happiest I’d felt in days—as if I’d just downed a handful of chocolate-covered espresso beans. I had conquered dozens of pounds of detritus! I was the reigning Queen of Trash!

But a few hours later, my high gave way to a sugar-crash low. The trash was gone, our garage roomier, but we were still in the midst of a historic pandemic.

Grief is like this: one moment, we catch a glimpse of relief. Or the gifts that loss and change always bear come into blazing focus, revealing the sweet meaning we’ll someday stitch from our sorrow. The next moment, we are weeping into our pillow or snapping at our kids because they had the nerve to ask for another effing snack or stuffing ourselves with bowl after bowl, just for instance, of popcorn dipped in a dizzying swirl of mayonnaise and Sriracha.

Longing for “normal.”

We miss normal. We struggle to believe how far from regular life we’ve veered. When we grieve a death, we’re often flooded with realizations of how special our loved one was, and we berate ourselves for not savoring every molecule of their existence when they were alive. Why, I wondered after my dad died, had I not listened more carefully to the lengthy, incredibly detailed stories he told me about his adventures in golf and poker? Why had I allowed my mind to wander as he spoke and spoke more, when someday those tales would be gone forever?

Similarly, we now long for “normal life.” Why, we might ask ourselves, didn’t we appreciate how amazing our old life was, with its mundane routines, annoying errands, and casual, carefree social contact? Grief shines an uneasy light on the sacredness of the ordinary.

Grief is labor.

We’re exhausted. Mourning is heavy work. Our hearts and minds are contending with the unpalatable, the unthinkable, the unbearable. The mental and emotional load we haul may make it difficult to concentrate on anything else. We may struggle to get out of bed in the mornings or count the hours until we can crawl back into our cocoons at bedtime.

Old wounds resurface.

Because we’re depleted, the demons we thought we’d outgrown may rise up, hissing in our ears. We haven’t vanquished them, it seems; they’ve just been patiently waiting this whole time, seeking the unsettled stillness of a global pandemic. We are stressed, yanked from our routines, and we are vulnerable. Last night, after dinner and a snack, I scraped potato chip crumbs from a near-empty bag into my mouth like a rabid raccoon. When I snapped out of my fat-fueled trance, I looked down at the chip-dust scattered across my lap. Who even am I right now? I asked myself.

I thought I’d banished my compulsive eating years ago, but there I was, covered in the oily-strata of my old demons.

Or the fact that I haven’t taught my kids to sit in the discomfort of their own boredom long enough that innovation sneaks in. I’ve always rescued them and played alongside them, even as I long for a handful of moments when I’m not needed. Now, together constantly, I can’t avoid this weakness, and yet I also don’t have the bandwidth to remedy it, to problem solve, and so I sit in the poison of my own discomfort, my own failings.

The second arrow.

Each time I’ve experienced deep grief, I’ve struggled to remain compassionate with myself. In Buddhism, there’s a concept called the second arrow. When we are hurt, we experience the initial wound, sore, and bleeding. But often our reactions to the injury become a second arrow. We puncture ourselves with blame or self-judgment over the initial damage. During the pandemic, I’ve nicked and maimed myself with dozens of arrows: for feeling bad that I’m an introvert who needs a lot of alone time—with my kids at home, I feel like a caged ocelot, pacing and radiating tension. For being paralyzed by the cascade of problems bubbling up in our household. For being susceptible to rolling waves of depression and anxiety.

Sweet girl, I remind myself in the moments I’m able to snag a patch of peace, dislodging the stinging arrows. You didn’t choose any of this, any more than you chose the color of your eyes.

The now-ness of grief.

Grief slows us down and barrels us into the present, even as it takes us on winding strolls to the past and the future. After my dad died last summer, the pain was breathtaking. Like physical pain, it jolted me into the moment. It hurt so much that there was only the deep pain in the center of my chest, only the steel-blue longing. I’d sit on our screened porch, listening to old Elton John songs and crying, or I’d perch on the floor of my room with my back to my bed, gazing at pictures of my dad from the summer before. Or I’d hold it in until I was alone in my car, knowing I should pull over as tears blurred my eyes, continuing my four-wheeled elegy anyway.

After a cry, I’d marvel at the sweet slice of relief, feeling the arch of pain recede, even while knowing I’d likely repeat the process a dozen more times that day. Long-term goals fell to the back of my mind—I could only focus on getting through each day, on riding each wave of grief and resting in the quiet space just after the crest.

It’s like this now, too. Grief can shake us awake, wrenching us from the trance of everyday life. There’s no map for when things might feel “normal” again, or even for when we might feel acclimated to whatever our new normal is.

I don’t know how else to get through this time, with its jagged edges and small gifts, but to attempt to stay present as much as possible. To accept the messiness of my own emotions along with our untidy world, to greet the deep insecurities and shortcomings that rise up, unleashed, with as much warmth and gentleness as I can muster. To be aware of the tendency to launch those second arrows and instead, drop our weapons, and tend to our existing wounds with fierce compassion. To remind ourselves and each other: this is hard, we’ve never done this before, and we didn’t choose this.

Just like with grief, I do best when I return my focus to the current moment, while also cradling the knowledge that I won’t always feel like this. We may never return to our previous selves or the society we were before, but the human mind and heart are built to adapt, to revise, to innovate. But just for now, absent an endpoint, I remind myself over and over again, we only have this breath, and this one, and this.

~

More Relephants Reads:

How does one Say Goodbye during a Pandemic?

5 Things your Dog wants you to Remember during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Read 10 comments and reply