“Trust your gut.”

“Use your intuition.”

“Listen; the answers are inside of you.”

For the anxious and the avoidant—particularly if these are maladaptive coping techniques dating back to adverse events of childhood—plus the traumatized, these terms can land like a second, incomprehensible language.

Our bodies and our senses are how we experience the world.

So technically the information to every conundrum is found “in our gut,” but accessing this murky black hole in the centre of our body from a state of disconnection can be akin to searching the ocean for a lost ship for some of us.

As a child, I was encouraged to narrow my range of expression. Loudness was not warmly received, be that happy trills and shrieks or angry outbursts. These were equally disruptive on either side of the spectrum.

Tears were shunned or, even worse, laughed at, as they created discomfort in the recipient.

It was my job to be emotionally “just right.” Not too happy, not too angry, and definitely not sad.

I became an expert at repression. But when we repress, we disconnect. We stop hearing the data our body is sharing. Eventually, that data either stops transmitting, or it simply passes underneath the threshold of our cognitive awareness.

I eventually came to a point in my life where I couldn’t ask friends to advise me on every little step because adults have too many micro-decisions to outsource. I recognized that I was painfully disconnected from my gut feelings and had no idea how to decode any information that might randomly slip through.

I was so well practiced at taming it back into submission that I usually wasn’t generating any information unless it was an intensely broadcast major announcement. Those happened every now and then, so I didn’t know anything was amiss—a lightning bolt of awareness every few years lined up with “the answers are inside you” because that’s how it had been for me since childhood.

However, when faced with a challenge, a professional advisor told me to “listen to my gut.” I looked at her with wide eyes and literally no clue what she was even suggesting I do—let alone how to do it. I knew that I had to figure out how to uncover my connection to the information inside me.

This was not easy. Because I buried this as a child, it has taken as much effort and practice in adulthood as would developing fluency in another language.

If you’ve spent your life, as I once did, with a disconnection between your gut and your conscious brain, here are some ways to connect back:

1. Start with our body.

The feeling is undeniably physically there, which makes finding data from it easier than from an amorphous “gut.”

We can tune into our body and notice specific sensations that we can put words to. Mutter them aloud, speak then silently in our head, or utter them under our breath.

Using our current intellect and the asset of existing language skills helps us both stay present and identify sensations, even if these are new concepts for us to feel in our body.

Notice what we feel and where we feel it.

For example:

>> Lie on your back and feel your spine. What do you feel?

>> Can you mentally locate a vertebra?

>> What does it feel like?

>> Can you locate one above?

>> Touch the spine if you want a kinaesthetic link to your words.

>> Now bring your legs together and come into a spinal rotation by bring them closer to the floor on one side of the body.

>> What do your vertebrae feel like when you come into a spinal rotation?

>> Where do you feel it?

>> What does a spinal rotation feel like?

>> How would you describe this sensation to someone who had never experienced it?

>> How would you describe it to someone who had?

Repeat, repeat, repeat.

We can use different body parts and different movements to sharpen our skills. I prefer yin yoga movements for this mindful awareness practice in the body, as the movements are slow and the time offered is lengthy. This helps us develop a mindful connection with a physical part of us that is unrelated to either emotions or decisions, and helps us with confidence in awareness skills, as much of this is verifiable without emotional attachment.

2. Identify our emotions.

If we were not encouraged to express emotion, or we lost our expression through trauma, we can begin to reconnect by familiarizing ourselves our emotions. Like developing a vocabulary for the body, tuning into our “gut” depends on having an awareness and a vocabulary for our feelings.

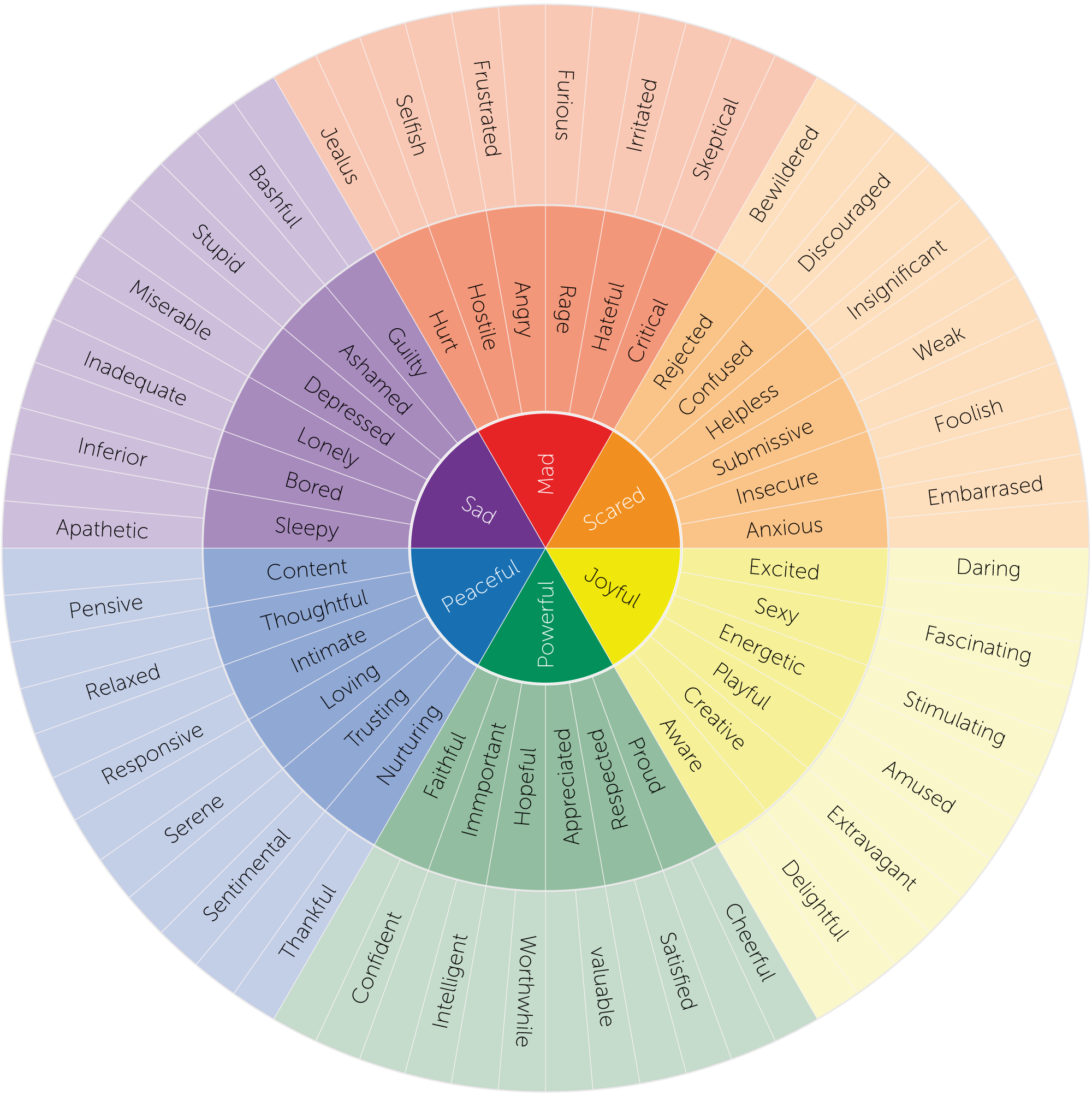

For this skill, I turned to the Wheel of Emotion, a colourful visual tool that helped me to name, identify, and put words to my feelings.

The wheel contains divisions that somewhat resemble a pizza, with the addition of three circular rings.

The inner rings contain six essential emotions, such as “mad” or “sad” or “happy.” The middle and outer circles expand the emotional range: “aggravated” and “hurt” are examples of more nuanced and detailed emotional possibilities of “mad.”

When I was first exposed to this tool, I could barely identify the inner ring emotions, the basic “pizza cuts” running through the middle ring. I honestly couldn’t tell if I was “sad” or “mad.”

Using the wheel, I learned that the subcategories of anger include: enraged, exasperated, irritable, disgusted, and jealous. And further expanded into the farthest spoke, which included: hateful, hostile, agitated, frustrated, annoyed, aggravated, resentful, envious, revolted, and contemptuous.

I had to do some heavy contemplation and introspection to determine which category and subcategory I was experiencing as I explored the myriad of expanded nuances.

>> Was I enraged or was I exasperated?

>> Was I frustrated or was I aggravated?

I was used to my body being more like an amorphous blob of: “something outside of the acceptable range is happening now, so I must stop it.” And I would then panic if I could not.

Learning to identify and name the emotion helped me to not panic about panicking. Using the Wheel of Emotion can help us develop a curiosity for what is happening rather than jumping to shame or discomfort that “an emotion” is bubbling up—or even worse, leaking out of us.

It’s a practice to notice and name the emotion, which helps us connect with our internal vocabulary. From this, we can gather some meaningful data from our body and therefore our intuition.

3. Look for areas where we move on instinct.

When it was time to “go with my gut,” I noticed that there were areas of my life where I moved on instinct. And other parts of my life where it was as logical as a portrait from Picasso from his cubist stage—the image made no linear sense.

Relationships were one of those areas; I had to ask friends for direction with every text and debrief every date.

Yet in my professional life, I moved easily through the decision of what to do next, even in major areas such as changing careers entirely or moving across the country to pursue a new opportunity. It was as though all of my instinct was channelled into a few narrow categories that received all of my gut expertise.

I utilized the areas where I was already masterful to create a blueprint for the weak areas: one part of my brain could teach the other.

We all have at least one area where we have some information coming from our gut, and we can use this to model to the areas where we need skill development.

>> What does it feel like?

>> What information are we getting?

>> How does it feel in our body or brain when we get this data?

In this way, we can use the area of greatest intuitive success in our life to model to the area of weakest intuitive success. We are then able to transpose the awareness of what we do in one area of life to others and “teach” the areas of weakness.

4. Practise sitting with yourself and not asking others.

Seeking “support” is a form of outsourcing our intuition. As much as we can get great advice and feel connected to others by doing so, if we are practicing connecting to our intuition, we need to practice cutting the cord of soliciting opinion.

This was the last, and hardest, step for me, as it was difficult to break the habit of consulting with friends, particularly around relationship advice.

When I started exercising more awareness around gut-led decisions in my professional life, I paid attention to my behaviour around soliciting feedback and advice. In this area of intuitive success, I noted that I not only didn’t ask for opinions when it came to my business instinct but also that I actively resisted unsolicited opinions.

I started to practice the same.

It took literal years to wean myself off the, “Hey, what should I do about this text/guy/conversation/relationship”—the weakest area of my intuition.

In recent times, I have only found myself saying, “I’m not asking for advice, I’m just venting,” but also editing the group of people I share difficult conversations with. Friends and members of our community want to help, which most often means giving advice, which isn’t always helpful for those of us who need practice finding our intuition.

Advice often firmly placed me in a seemingly endless loop of analysis and intellectual dissection, as each suggestion or nuance added to the problem and took me into my head and out of my body.

It’s a practice to develop resilience with discomfort and uncertainty within ourselves, rather than soliciting solutions from others. This may temporarily soothe, support, and assist, but it doesn’t help us develop the skillset of inner knowing.

~

To someone without a developed sense of intuitive awareness, the scariest advice to be given is to “look inside, you have all the answers within.”

We may not know how to hear what our body is telling us or what to do with that instruction. Like learning a new language, this is a skill that can be honed at any age, no matter how turned off that intuitive connection currently is.

~

Read 31 comments and reply