View this post on Instagram

My cat, Pansy, left her body on March 17, 2021 — just at the beginning of the sweetest, most bitter spring ever.

Pansy season — on St. Patty’s day, nonetheless. Her name when I adopted her was Patty, and I thought her choice to leave on that day was her last, special wink to me.

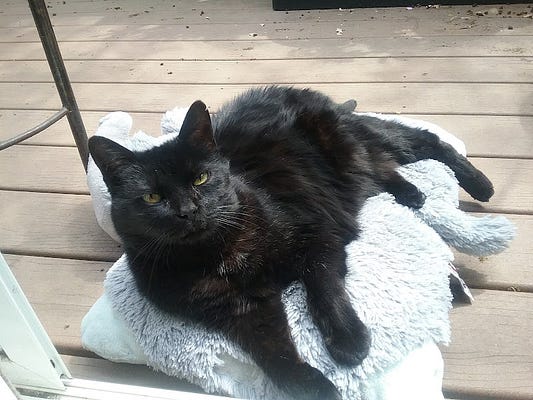

(Pansy, so beautiful, during her last days)

After a particularly difficult time in my life, I adopted her when I had survived and, mostly, recovered from a traumatic brain injury. Any trauma is dehumanizing, and when I saw her, I felt that she understood what it was like to be given up on, marginalized, and discounted.

From the beginning, I saw her sweetness. She licked me on my thumb, and I remember thinking that if she is this sweet in such a trying circumstance — the shelter — she must be a keeper. I changed her name to Pansy because I believed Patty was an unsuitable name for a cat and because pansies have always been my favorite flower.

The writer in me loves the irony when people call Pansies weak and “sissies,” but in truth, the pansy is one of the most resilient plants. Pansy, too, was an imminently sweet being, but she was one of the most resilient, strong beings as well. I saw in her eyes a deep sense of knowing. I understood that in her heart there was a sense of love and forgiveness. She was abandoned by her humans at the pound, morbidly obese, over 10 years old, and declawed on all four feet. Yet she held no resentment about any of it, at least as far as I could see. What I could see was all the magic and beauty in her eyes. The love and the softness in her soul.

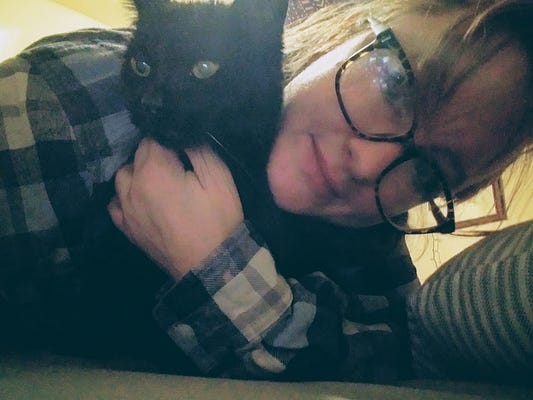

(I saw, in her eyes, a deep sense of knowing.)

Soon after I got her, I questioned my decision, not knowing if I could take care of her — I was still recovering, and I realized her health issues were significant. I did not know if I would be a suitable caregiver. I even tried, briefly, to re-home her. But none of it worked out. Ultimately, I felt that I needed to protect and love this being as deeply and as well as I could.

Maybe it was a sacred contract.

Maybe it was just love.

Loving her helped me heal my heart and the “mother” wounds I carried. My mother, although she materially provided for me, was never emotionally present. She was difficult when it came to being there for me . I didn’t really know what having a loving family felt like, to be honest, because so much of my childhood was extremely lonely and subtly and overtly traumatic.

I didn’t know what it felt like to have unconditional support.

(Her presence made me feel connected, whole, and, maybe for the first time in my life, not completely alone.)

But Pansy and I found one another and, I believe, we changed that for one another. I know she helped me heal in ways no other being has. She softened so many rough edges for me in life, and in her quiet way, she supported my dreams and ideas. Her presence made me feel connected, whole, and, maybe for the first time in my life, not completely alone. She moved to a new state with me, adapting to life on a farm and then in a new city. She never wavered in her support or her attentiveness to me. I adored caring for her, making her comfortable, making sure she felt safe. Looking back, so much of my purpose was spent caring for her, worrying about her, doting on her. And oh, how I miss that now. I felt like we were in it together as teammates and best friends.

No matter what, she accepted me. No matter what, she was always there when I got home.

(No matter what, she was always there when I got home.)

She was not like other cats. She was eminently calm, like a feline Buddha. She would walk outside with me, supervised, and follow me even without a leash. She would go up to people, friendly like a dog. Her body comforted me with its roundness and sweet scent.

I used to bury my head in her fur and sob sometimes. To me, she symbolized healing, beauty, innocence, and wholeness. Not just symbolized , she was an embodiment of all of those things. And she had a wonderful sense of humor. It’s funny to me how verbal we are, and how animals can communicate these qualities so deeply without saying a word.

Pansy always had health issues, which I did my best to address as her mom. She had arthritis and difficulty walking from both her declawing and her obesity , and I knew that lack of mobility was frustrating for her. As she grew older, her kidneys started to fail, but a special kidney diet ameliorated that.

(I loved taking care of her, I even miss worrying about her, thinking of how to help her, how to make her more comfortable.)

At the end of February 2021, Pansy seemed to be having an extremely difficult time breathing. I took her to the vet — and they diagnosed her with pneumonia and “pleural effusion,” meaning she had fluid in her chest cavity. I took her home with a sinking feeling in my chest. Somehow, I knew it was serious. I still did my best nursing her back to health, giving her food at all times of the day, bathing her, making sure she was comfortable.

(It was easy talking myself out of the elephant in the room — that my baby, my best friend, my only real family member — might soon be gone.)

And yet, I have always believed in the sovereignty of each being. I knew Pansy felt my love and attachment and need for her, and she was sticking around because of it. This made me feel guilty . I knew that as her mom, my next biggest gift to her would be to respect her wishes. I consulted a pet communicator who helped me immensely. As I spoke to the woman on the phone, Pansy was completely involved in the conversation — head perked and ears up the whole time. The communicator helped me understand that Pansy was getting ready to leave her body.

(She had loved being a cat, and she had loved her body. But it wasn’t feeling good any longer.)

The communicator also told me that Pansy did not want to be euthanized, that she wanted to die naturally. Reflecting on that later, I realized that being at the shelter, she must have picked up on what was happening in the background — unwanted animals getting “disposed of” in that way.

The communicator also told me how much Pansy loved rose quartz, and so I put the stones I had in the seams of her bed. She immediately moved over to that side of the bed. Over the next few days, I bought more rose quartz and fresh-cut flowers for her, as well as potted pansies. The first flat had just arrived a day earlier at the local greenhouse.

I shared so many beautiful moments with Pansy as she was getting ready to pass. I told her how much I loved her and how much she meant to me. I told her I was sorry for the times I felt like I could have done better as her mom. I sang her songs, including Alanis Morrisette’s homage to motherhood “Guardian.”

(We watched movies together — I moved my mattress into the living room to be with her. Pansy liked silly movies — we watched all three “Austin Powers” movies, as well as “Mars Attacks” together.)

A couple of weeks later, she seemed much better, in the way that cats always seem to bounce back. Maybe, she was not really ready after all, I thought, optimistically. I took her to the vet again and found out the opposite was true — her kidneys, lungs, and heart were all like an unstable Jenga tower. She was getting ready to let go of her physical body. And the vet was prevented from doing anything — she would not even risk getting the fluid out of Pansy’s chest because the procedure would put her enlarged heart at risk.

Pansy’s last day at the vet was on Sunday, and she passed that following Wednesday.

I feel that Pansy led me kindly and gently to the vet to say, “Hey, mom. You did everything you could. I am just ready for the next adventure.”

Throughout this, I had immense guilt and fear of death — both of which were necessary to work through. The guilt was in the face of the powerlessness of the inevitable , that Pansy would not be there to come home to, that she would not be my rock, my comforter, my best companion, and friend. And fear of death was something deeper. Primal. And uncomfortable, to say the least.

But throughout Pansy’s last days, I remained committed to honoring her, committed to respecting her as a sovereign being. I told her I would stay with her no matter what, I would protect her and would always be with her — we are both Scorpio people after all, I told her . We can handle this stuff! I continually consulted my therapist, who had previously worked as a hospice nurse, about the changes happening in Pansy’s body. Her body was shutting down, and there was something so poetic about it at times. In our modern, medically biased world, death is seen as an anomaly. Organs that are shutting down are “failing” instead of succeeding at dying. It took everything not to blame myself for not being able to stop the inevitable end that she was coming to. But with help, I was able to center myself, continually check in with Pansy’s spirit in meditation, and reaffirm that all was well and completely natural.

On the morning Pansy passed, I took a long drive into the mountains. I was praying for her and saying, “God, please protect and welcome Pansy for her highest and best good” over and over.

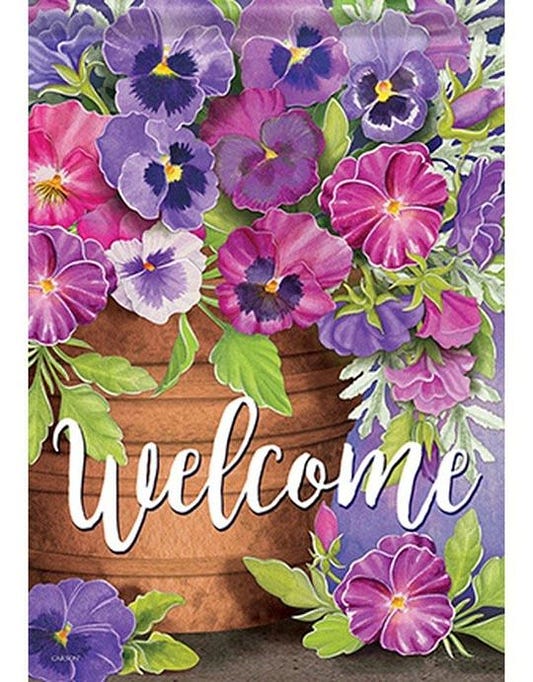

(I never use the voice recorder on my phone, but I looked down and saw a whole page of flags that said “Welcome.” They were all decorated with pansies.)

When I got home, I felt peaceful and accepting of Pansy’s death in a way I had not felt through the process, and I think this helped her let go. I took Pansy into the backyard in a basket with a blanket on her. I surrounded her with crystals, rose quartz, and potted pansies, and told her that I loved her, over and over, and created energetic protection around her. I lay down next to her basket, and I moved the basket with the sun’s path so she could enjoy her last sunset. I drew her and wrote about her — how special she was and how much I loved her. She was always so beautiful, even hours away from death. Her scent remained clean and sweet.

(Her soft body reverberated with the sweetest, most gentle of purrs.)

As the afternoon turned toward the evening, I went inside to clean and prepare a fireplace fire for her. I didn’t know how long she had left, but I wanted to enjoy it, and she loved fires. But Pansy got up from her comfortable basket and stumbled around the yard, letting out a guttural howl. It was her way of saying, the wild birthed me and the wild will reclaim me. Still, as she staggered around I couldn’t help following her around with a pink blanket. It was so hard, so painful to not want to care for her, to not want to make her comfortable. But what had been helpful for so long was now making her transition more difficult.

And so, I left again, sensing my presence and our bond would only make it harder for her. I drove deep into the desert night, praying to help her let go, praying that she would be protected. I started breathing deeply and sending her the feeling of release, still wanting to be as present with her as possible, though I know it would have only made it more difficult if I were there.

I could feel her relief the moment she passed, as I was circling Santa Fe Plaza. Coincidentally, it was also the moment I passed an art gallery — the “Rainbow Gate.” When I returned home, she was gone, but her body was still warm. I sat with her a while, covering her with pansies, amazed at how bodies are designed for movement so beautifully even when there is no “mover” in them.

(Death makes you so present, so aware of even the smallest things.)

I felt so much gratitude for her sharing her life with me, and in the end, sharing her death. I wish I could have let go of the guilt and resistance to her death sooner, but ultimately, I believe I respected her wishes and was present with her to the very end.

This kind of “mother” love requires much of us — to love deeply, to protect, to care — but it also requires us to painfully and ultimately let go. It can tear at the heartstrings to feel so much simultaneously, and letting go of Pansy required me to look deeply inside of myself beyond my fears and guilt and to see the truth and the beauty of death.

I had never intimately experienced death and been so present with the process, as I had with Pansy. Death was always at arm’s length in a hospital or vet’s office, and it was always something to fear. There was something “wrong” with it. But Pansy taught me that it was natural, poetic, and even beautiful. She taught me the importance of connection, trust, and nurturing. And in the end, I learned the ultimate lesson anyone who loves deeply has to learn eventually — to let her go, to recognize her sovereignty, that she was never “mine” to begin with. And yet, I know that wherever she is, she is still with me, watching me, loving me, and purring into the soft clouds of infinity.

~

Read 14 comments and reply