When mistakes turn out to be blessings:

No, I’m not referring to the divorce decree you gleefully clutch—for the second time—or the realization that wounds from a life of wretched but eerily similar self-destructive behavior are finally over by, say, 50. This is about a late-life epiphany at the mature age of 70, a long-ago screw-up and deeply embedded regrets without the possibility of atonement. At least until recently.

I’m about seven weeks into fatherhood—for the first time and in a big way.

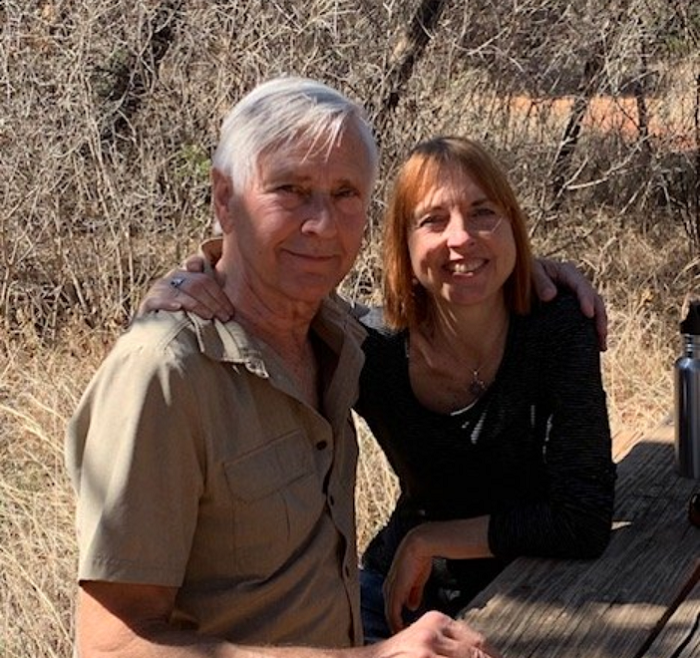

Never mind that I have hard-earned white hair, Social Security benefits, bifocals, and a great marriage on the third try, but now there are newfound birth daughters (identical twins), who were likely throwing darts at a board with sticky notes bearing various forms of address to define my new status.

“Daddy?” Nope. That would entail imperfect school plays, dissonant music lessons, enervating first dates, and driving the family car.

“Father?” Nope. Too authoritarian.

One possibility came from one of my daughters’ posse: BFF or Bio-Father Forever. It struck the right note, a perfect cocktail of hip jargon, and respectful with a tincture of humor.

A nod to picking the appropriate word or phrase turned out to be the sweet spot for me and daughter Marci. As it turns out, she and I are both writers. Could that have its origin in the genes we shared? Though our nexus unfolded after my initial message from Ancestry.com, news of adult daughters now entering my life was a jolt, but not a surprise.

The email from Ancestry lingered in my inbox for three days before my wife Alice opened it and said, “I think you should read this.” I did. It gave me a name: Marci Laughlin, Relationship: parent/child.

Two years before, Alice and I signed up, ostensibly, to get a clearer picture of our families’ heritages. There was also something about if you wanted to be connected with others who share your DNA. Well, sure. While we filled out the questionnaire, Alice said, “This means your daughters could find you. Are you okay with that?” I said sure. It was a possibility, though an unlikely one after a 48-year lapse since I was 19.

It was the summer of ’68 when I heard from my girlfriend, with whom I’d broken up before returning to my home state of Minnesota. It was an “I miss you” phone call. I echoed her sentiments. A moment of silence followed our mutual declarations. Her voice trailed into an emotional whisper…”I’m pregnant.” It had none of the joy this invocation usually carries. Instead, my panic was instant. The only thing that sprang to mind was an offer to send some money to help her out—a gesture disproportionate to the occasion.

Throughout the following months, we communicated infrequently. The girls were born in late December of that year in Southern California. Four months later, their birth mother put them up for adoption. Our communication ended after that. My most lasting souvenir was her statement: “The girls are beautiful.” I never forgot their births, though my conscience was wrought with a combination of guilt and impotence for 50 years. And the prospect of finding them five decades later? I guess I could still hope.

Assuming the obligations of parenthood at 19 was a nonstarter. I knew I was too immature and removed from the pain she endured when having to surrender her four-month old daughters. Unimaginable for any mother. But, at 18, the prospect of single motherhood, and caring for two infants, must have seemed an onerous responsibility and, perhaps, a future-less existence.

What I’ve come to better understand decades later is the gravitas of cellular memory. So, poised at the threshold of meeting my daughters—now—would that early abandonment leave some psychic scar tissue with consequences? The unknowns were too numerous.

“I often thought that one day I would get a phone call beginning with the words, ‘You don’t know me, but…,’ girding myself for some haunting reminder of things I’d done or said, evidence of past behavior that makes me cringe—like the twin girls I had fathered but never knew.”

I penned these regret-tinged words years ago in a memoir. Seven weeks ago, Marci gave me a reprieve from that seizure of guilty conscience. A sense of serenity has transformed me since her first response to my self-introduction in Ancestry’s message center:

Dear Mark,

Hi. I just now looked at my DNA results, and still have no clue about how to make heads or tales of this website. So I’m not even sure how you were able to message me…I appreciate your very prompt response. But I still have no idea who you are, or what your connection is to me and my sister? I’m literally on the edge of my seat, so would very much appreciate hearing more from you as soon as possible.

I wrote back to her:

Dear Marci,

The message I received from Ancestry notified me of our connection. It indicated: parent/child. I guess that didn’t show up on your end. However, it confirmed what I’ve known since you were born—that I’m your father.

With warmest thoughts,

Mark

I still marvel when witnessing the skills required in parenting, and automatically assume undertaking adoption elicits an eagerness, readiness, and depth of devotion that adoptive parents bring to their commitment. So, how could the abdication of my biological and fiduciary duties be viewed after a half century of silence? It could be seen as willful lack of caring about their lives, their destinies. And, if that notion held sway, maybe they want to hunt you down, stake you out on the Sonoran desert, cover you with honey, and let the ants gnaw leisurely on your carcass. Anyone who’s gone through an acrimonious divorce suspects a latent revenge factor is always near the surface and a powerful motivator. So, maybe there’s a Fatherhood for Dummies I could consult for clueless men. (Possibly a pop-up version.) The demographic should warrant it.

The competing pull of the nature versus nurture debate is open to speculation. For decades, I thought the biological link could not trump what I suspected to be the “white picket fence” existence in which the girls were raised. The rigors of the adoption process were well-known in the late 60s. The parents survived the bureaucratic gauntlet, were scrutinized, and given the state seal of approval.

Perhaps it’s the intrigue of the unknown, the universal drive to know our roots, to ask and answer that key question: Who am I? If this were my daughter’s motivation, I could help. However, I couldn’t yet assess if her outreach meant she wanted more than information, maybe a relationship. By this time, a dizzying array of possibilities paraded through my brain. Propriety suggested approaching this juncture with candor and caution. My inner hedonist urged instant gratification, an outpouring of anticipatory feelings, hopefulness that this deep-impact encounter might establish diplomatic relations, friendship, and mutual exploration of a whole new terrain.

To my endless delight, it has.

This new connection has inexorably changed my life and my daughters’. It has prompted tears of joy I never knew I harbored. Our abbreviated emails have blossomed into treatises on the nature of love, expressions of hopes, fears, plans to explore a future together, to grow as a daughter and father, to fulfill the rich potential of our creativity and chronicle the greatest journey of our lives. And, for the first time in my life, I understand the magic bond of the parent and child. It is a blessing without equal.

My feelings of regret are gone, replaced with a promise to my daughters to never forget to tell them often: I love you and always will.

~

Author’s note: This blog is connected to Marci Laughlin’s series on Elephant Journal: Struggles of an Adult Adoptee. You can follow along here.

~

Read 12 comments and reply